Research from consumer organisations and BETTER FINANCE member organisations far too often points to the heavy-handed practices of debt collectors when dealing with defaulting and distressed borrowers.

A loan (credit) is “non-performing” when it’s either over 90 days

overdue or unlikely to be reimbursed by the client (business or

consumer). In this case, credit institutions (e.g., banks) can resort to

one of the three following recourses:

- either “work it out” with the customer, e.g., grant a moratorium (postponement), restructure the repayment, discount the loan, etc.;

- take legal action, e.g., foreclose, liquidate or otherwise enforce the guarantees, if any; or

- sell the non-performing loan (NPL) to a debt collector.

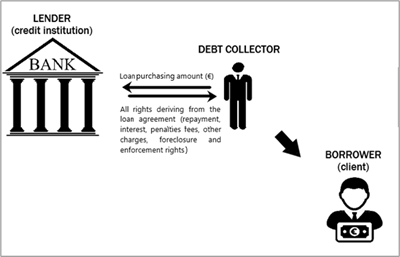

Credit institutions very often choose the latter – selling NPLs to

debt collectors – as a fast way out: the bank quickly gets a part of the

loan back and moves on, while the debt collector substitutes the bank

in the contractual relationship (lender – borrower) with the client.

In theory, it all sounds fair and efficient.

©BETTER FINANCE, 2021

However, the reality is very grim for borrowers who cannot repay

their loans. First, defaulting on a loan will cause the initial amount

to mushroom due to all related penalties, interest, fees, and other

charges which must be borne by the borrower. Second, assets (securing

the loan) will probably be liquidated below par value, increasing

pressure on the borrower.[1] Last, debt collectors are not known for their sympathy when trying to recover the amounts borrowed.

Research from consumer organisations[2]

and BETTER FINANCE member organisations far too often points to the

heavy-handed practices of debt collectors when dealing with defaulting

and distressed borrowers. From harassment to charging excessive fees or

speculative profit margins, debt collectors in many EU Member States put

consumers who are not able to pay or continue paying their credits in a

very stressful and difficult situation.

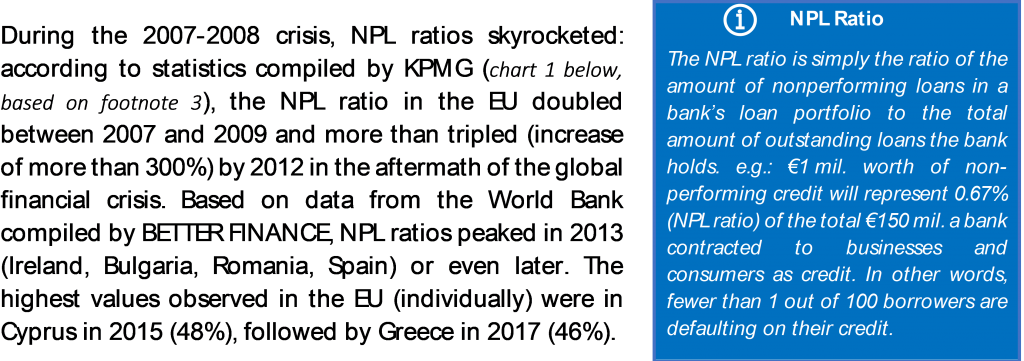

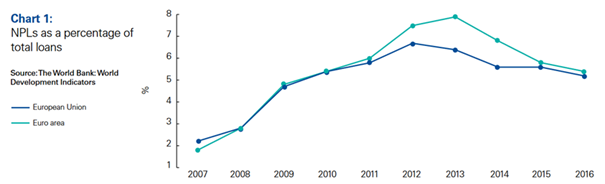

The current state of NPLs and the COVID-19 Aftermath

Source: KPMG, 2018 (see footnote)[1]

Recent EU financial policies have been successful in reducing the

volumes and ratios of NPLs in the EU. By the end of 2019, the share of

NPLs returned to below 5% in 76% of EU Member States. On average, the

European Central Bank reported a share of 2.8% of NPLs for the third

quarter of 2020 (end of September).[2]

However, the restrictions imposed in response to the COVID-19

pandemic may have significantly affected the capacity of many consumers

and businesses to repay their loans. Although 2020 marked a new low for

the NPL ratio, it is expected to rise again across the EU once aid

measures (e.g., moratoria or forbearance) cease.[3]

What can be done?

EU financial policy has focused on the macro-side of the NPL issue, essentially aiming to help banks deal with large NPL ratios.[4]

Proactively, the European Commission currently attempts to prepare the

EU banking sector and Governments for what could hit them in the

aftermath of the COVID- 19 crisis through a series of legislative

measures such as the NPL secondary markets proposal or by coordinating

the set-up and management of national “bad banks”.[5]

While such strategies have merit, they are not sufficient, since

distressed banks will reduce their funding (credit) capacity to the

economy and also put deposits at risk. Freeing up space on banks’

balance sheets should not be done without enforcing responsible lending practices, financial education and retail saver protection. The measures proposed by BETTER FINANCE hereunder aim to either prevent the build-up of NPLs or to adequately help and protect non-professional debtors when they default on their loans....

more at Better Finance

© Better Finance

Key

Hover over the blue highlighted

text to view the acronym meaning

Hover

over these icons for more information

Comments:

No Comments for this Article