First, I will compare Eurostat’s flash estimate of Q2 GDP (published last Friday) to the June Eurosystem staff projections.[1] Second, I will discuss the role of the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) in supporting the euro area economy and protecting medium-term price stability.

Second quarter GDP: the maximum impact of the pandemic

It has

long been clear that the maximum impact of the pandemic on economic

activity would fall in the second quarter. While the economy had already

taken a significant hit in the first quarter, the most extensive

lockdown measures were implemented in April. Higher-frequency data

indicate that there was some recovery during May and June (on account of

initial progress in stabilising the spread of the virus and the

associated easing of lockdown measures), but the scale of the April

contraction and the partial nature of the rebound in May and June meant

that the data would inevitably show a substantial decline in the average

level of economic activity during the second quarter.

Eurostat’s

preliminary flash estimate for euro area output in the second quarter

makes for sobering reading, with a quarter-on-quarter decline in GDP of

12.1 percent. Taken together with the 3.6 percent decline in the first

quarter, the cumulative decline in output in the first half of 2020 was

15.3 percent.

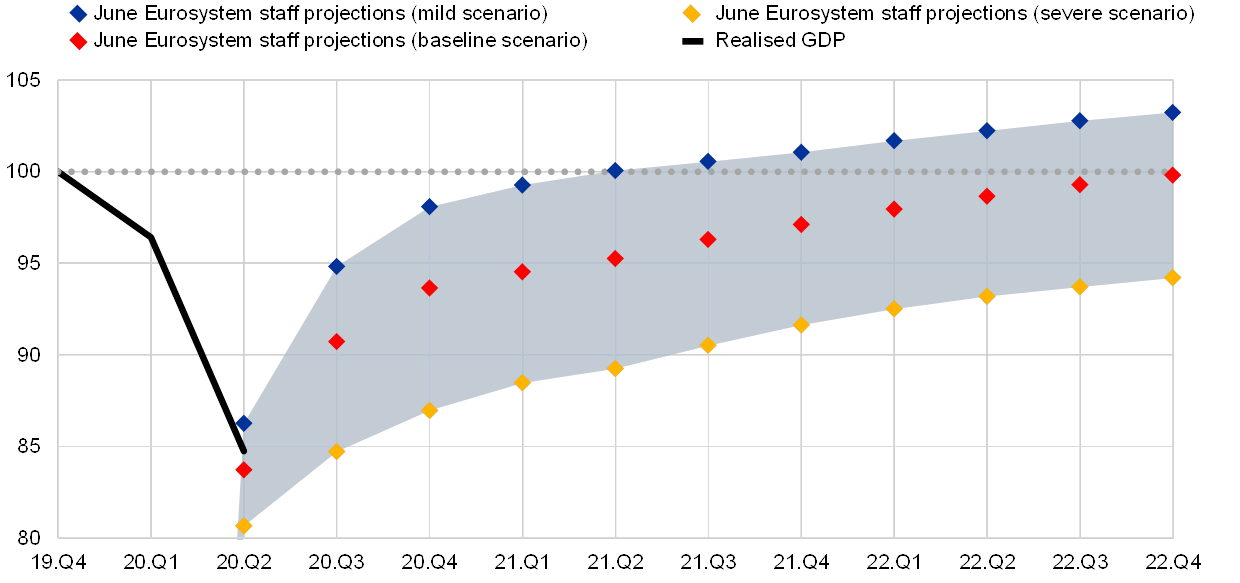

As shown in Chart 1, the second quarter outcome is

slightly less severe than the 13 percent decline envisaged in the June

Eurosystem staff projections. Across the range of scenarios studied by

the Eurosystem staff, the third quarter is projected to see a

significant increase in the level of economic activity, even if the

scenarios differ in terms of the overall duration and severity of the

pandemic shock, with the baseline only seeing a return to the

pre-pandemic level of economic activity in 2022.

Chart 1

Realised and projected output

(indexed real GDP, Q4 2019 = 100)

Sources: ECB and Eurostat.

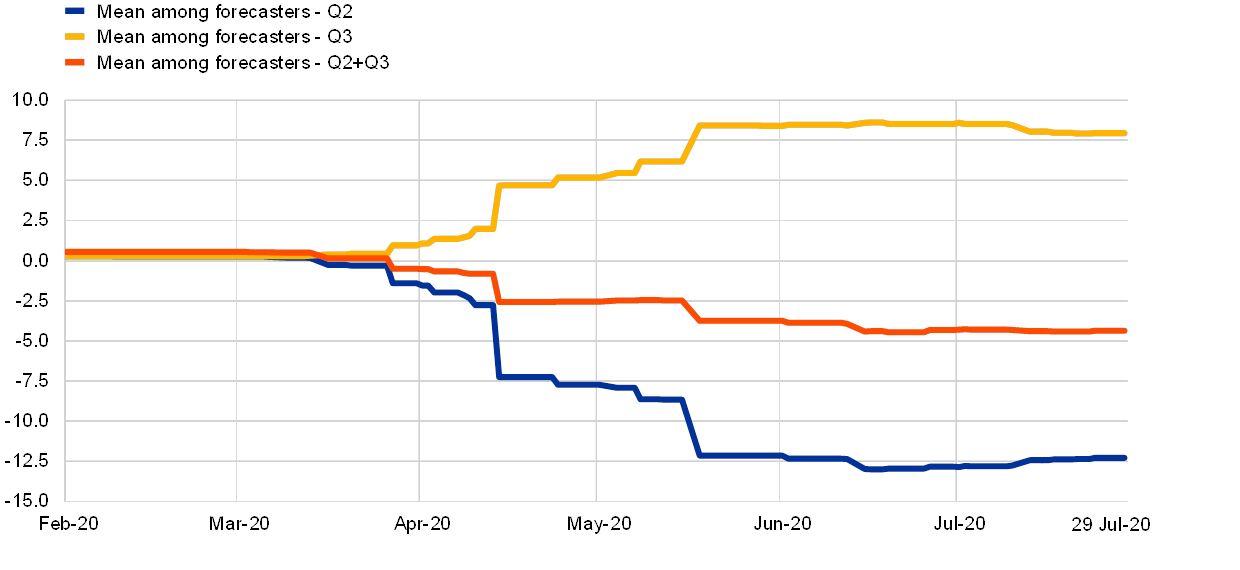

In

drawing inferences from the flash estimate published by Eurostat, it is

also important to take into account the negative correlation in many

forecast exercises between the second-quarter and third-quarter output

growth rates (see Chart 2). In particular, to the extent that the

unlocking of the European economy advanced more quickly in May and June

than was originally expected, this may imply a less-steep step up in

economic activity in the third quarter, with more sectors transitioning

from the reopening phase to a more gradual growth rate. Accordingly, it

would be unwise to draw strong conclusions from the second quarter

outturn: at the least, the data for the second and third quarters should

be jointly assessed.

Chart 2

GDP growth forecasts by private banks for the second and third quarters of 2020

(percentages)

Source: Bloomberg.

Notes:

Private forecasts are provided by the 29 largest commercial and

investment banks. “Mean” refers to the average of the forecast among

private banks. The latest observations are for 29 July 2020.

In

analysing the prospects for the third quarter, the containment of the

virus remains the most important factor. The rise of new coronavirus

(COVID-19) cases in parts of Europe over the past couple of weeks has

led to renewed local containment efforts and revised travel guidelines.

In addition to the direct adverse impact on some sectors (especially

tourism), setbacks in the containment of the virus are also weighing on

consumer and investor sentiment. In a similar vein, the resurgence in

COVID-19 transmission rates in a number of major non-euro area economies

is dampening sentiment and impairing spending in those economies, with a

measureable impact on the external demand for euro area exports.

More

generally, the exceptionally-elevated uncertainty about the evolution

of the pandemic continues to dampen business investment. Taken together,

actual and expected declines in employment and income can be expected

to keep precautionary household savings at elevated levels. Moreover,

while overall bank lending conditions remain favourable, the second

quarter bank lending survey signals that banks expect a net tightening

of credit standards for loans to firms, in part related to the projected

tapering-off of state credit guarantee schemes. These factors help to

explain why the economy is expected to take a significant amount of time

to recover fully from the pandemic shock and why significant fiscal and

monetary policy support is necessary.

The role of the PEPP in supporting the euro area economy

As

the severity of the economic and financial implications of the pandemic

crisis became apparent, the ECB adopted a series of measures to ease

financial conditions in order to avoid adverse feedback loops between

the financial system and the real economy, support confidence and

proactively respond to the downward shift in the outlook for growth and

inflation.

More specifically, the ECB acted through its liquidity operations and

asset purchases, which included the establishment of the PEPP.

As I described in an earlier blog post, the PEPP has a dual role.

First, alongside the ECB’s other monetary policy instruments, asset

purchases are the most important mechanism for delivering the additional

monetary accommodation required to support the economic recovery and

safeguard price stability in the medium term. Second, the flexibility

embedded in the PEPP – across time, asset classes and jurisdictions – is

essential in enabling the ECB to stabilise financial markets in an

efficient and effective manner.

Let me begin by discussing the

latter role in more detail. The PEPP’s market stabilisation function has

proved successful in recent months, with the ECB making use of the

PEPP’s flexibility by frontloading asset purchases and directing them to

those market segments where they have been most warranted. The risk of

fragmentation has been significantly reduced since the onset of the

pandemic crisis.

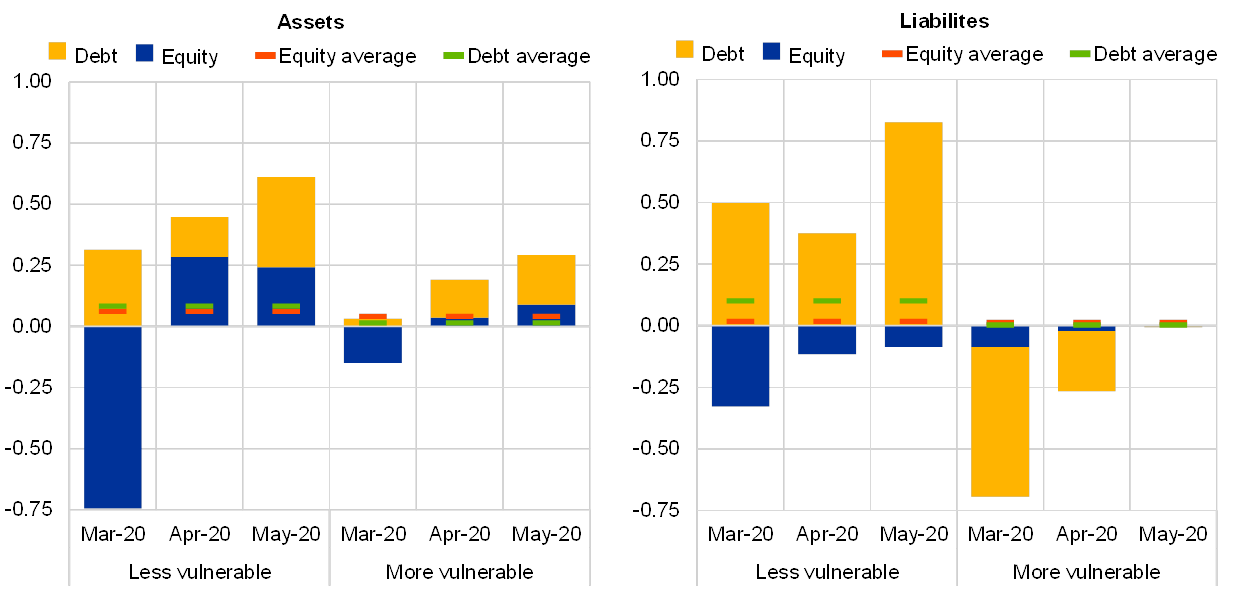

Chart 3 illustrates this point with balance of

payments data for March, April and May across two country groups (less

vulnerable and more vulnerable). Following the severe fragmentation

patterns that began to develop in March – patterns consistent with the

nature of a flight-to-safety episode – signs of stabilisation emerged in

April and were even more evident in the May data. On the asset side,

net inflows into both less and more vulnerable countries increased (left

panel); on the liability side, net outflows of debt securities issued

by more vulnerable countries came to a halt, after two months of

sizeable net sales (right panel).

Chart 3

Cross-border portfolio investment flows by country group – assets and liabilities

(monthly flows as a percentage of euro area GDP)

Sources: ECB and Eurostat.

Notes:

Data recorded on the basis of the Sixth Edition of the IMF Balance of

Payments and International Investment Position Manual (BPM6). Averages

calculated from January 2008 to May 2020. “Less vulnerable” countries

are Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany and the Netherlands;

“more vulnerable” countries are Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain.

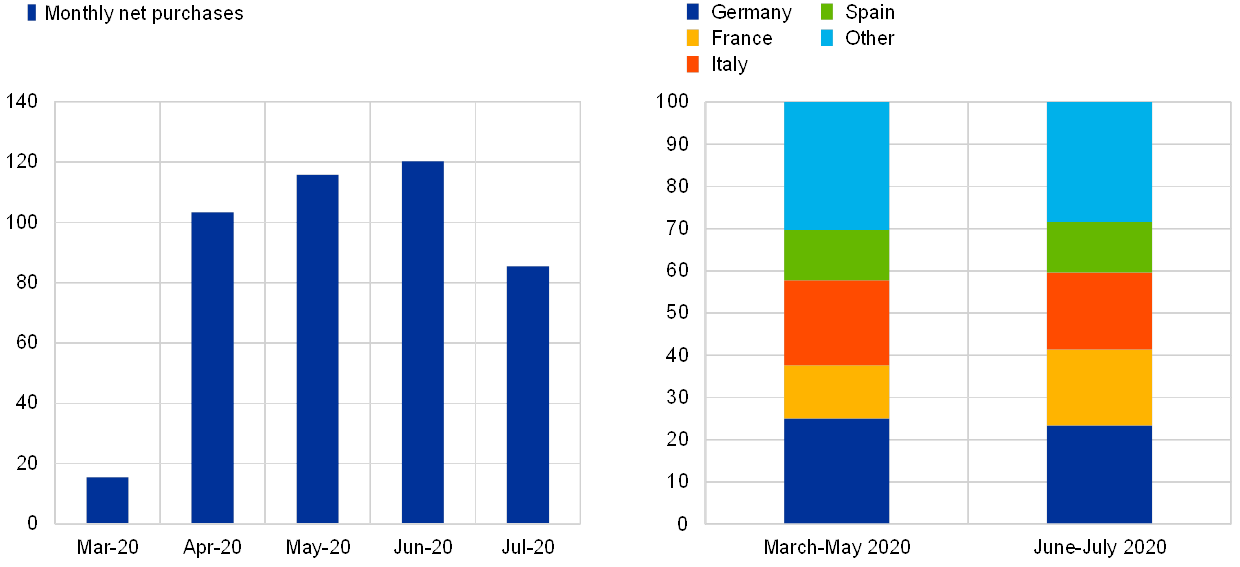

The

success of the PEPP’s market stabilisation role to date, combined with

the flexibility embedded in the programme, has allowed for adjustments

in the timing and composition of purchases in line with the evolution of

market conditions. Taking this into account, and keeping in mind the

usual summer lull in market activity, the latest PEPP data releases show

that there has been a reduction in the pace of PEPP purchases in July

(see Chart 4, left panel). Purchases of public sector securities in

those countries that were most affected early on by the pandemic have

also been adjusted as market conditions have improved (see Chart 4,

right panel).

However, while the monthly pace and composition of

the PEPP can be flexibly adjusted in line with the risks to market

stability and the transmission mechanism, the overall envelope of PEPP

purchases is a core determinant of the ECB’s overall monetary stance.

In line with the ECB’s price stability mandate, the inflation outlook

plays the central role in determining the appropriate monetary stance.

Prior to the pandemic, the December 2019 Eurosystem staff projections

for the euro area foresaw annual HICP inflation at 1.6 percent in 2022.

In the June 2020 staff projections, the outlook for HICP inflation in

2022 had been revised downwards to 1.3 percent. This downward revision

to the inflation outlook motivated the scaling-up of the PEPP envelope

from €750 billion to €1,350 billion at the June meeting of the ECB’s

Governing Council.

Chart 4

Eurosystem purchases under the PEPP

(left

panel: total monthly net purchases, EUR billions; right panel:

geographical distribution of public sector securities purchases,

percentages of total public sector securities purchases during

respective period)

Source: ECB.

Notes:

End-of-period book values. Figures are preliminary and may be subject

to revision. The monthly purchase volumes are reported on a settlement

basis and net of redemptions.

Conclusion

In summary,

while there has been some rebound in economic activity, the level of

economic slack remains extraordinarily high and the outlook highly

uncertain. Further progress in persistently containing the virus will be

central in determining the size and speed of the economic recovery,

together with sufficiently-supportive fiscal and monetary policies. In

tandem with the appropriate calibration of national fiscal policies and

the various EU-level initiatives already announced in April, the

recently agreed Next Generation EU (NGEU) instrument will be vitally

important in ensuring sufficient fiscal support across EU Member States

in the coming years. For our part, the ECB is committed to providing the

monetary stimulus needed to support the economic recovery and secure a

robust convergence of inflation towards our medium-term aim.

ECB

© ECB - European Central Bank

Key

Hover over the blue highlighted

text to view the acronym meaning

Hover

over these icons for more information

Comments:

No Comments for this Article