The EU’s ambitious emissions reduction targets will require a major increase in green investments. This column considers options for increasing public green investment when major consolidations are needed after the fiscal support provided during the pandemic.

The authors make the case for a green golden rule allowing green investment to be funded by deficits that would not count in the fiscal rules. Concerns about ‘greenwashing’ could be addressed through a narrow definition of green investments and strong institutional scrutiny, while countries with debt sustainability concerns could initially rely only on NGEU for their green investment.

Increasing

green public investment while consolidating budget deficits will be a

central challenge of this decade. The EU has set the ambitious goal of a

55% greenhouse gas emissions reduction by 2030 compared to 1990 and

zero net emissions by 2050. This will require a major increase in green

investments, of which is a sizeable part should be public investment. At

the same time, major fiscal consolidations are needed after the

extraordinary fiscal support during the Covid-19 crisis. The

consolidations will be framed by European fiscal rules. Past

consolidation episodes resulted in major public investment cuts. How can

the EU ensure that public investment will increase when fiscal

consolidation is implemented?1

The fiscal rules debate

A buoyant academic

and policy analysis literature has assessed the EU fiscal rules. We see a

broad consensus on the fact that the current rules face technical

problems (measurement of potential output and structural balances) and

are not well implemented, but not on other questions, including on the

role of judgement, country-specificity, and the degree of centralisation

in fiscal surveillance (e.g. Martin et al. 2021).

A comprehensive and

broad-based reform will hence take time and is unlikely to be completed

by the reinstatement of fiscal rules in 2023, but the need to increase

green public investment is imminent. In this column, we assess the

scope for adapting the rules to make room for increased public green

investment.

Green investment needs to meet EU targets

European Commission

scenarios suggest an immediate expansion of annual investment in clean

and efficient energy use and transport by about 2% of GDP in order to

reach the EU’s climate targets (European Commission 2020). This estimate

is in line with those of D’Aprile et al. (2020) for the EU and the

International Energy Agency (2020) for the world, among others. It does

not include the cost of flanking social policies which cannot be

regarded as green investment.

The share of the public and private sectors in green investment needs

Most of the new

investment has to be private, but the public share will be significant.

For overall climate-related investments in energy and transport, the

2019 National Energy and Climate Plans foresaw an average 28% public

funding share in the EU (European Investment Bank 2020).2 If

one assumes that the new additional green investments were in line with

this 28% public share, an annual additional public investment of about

0.6% of EU GDP would result. This is a major fiscal effort that will

need to be financed.

The share of public

funding can be reduced by appropriate government regulation, taxation

policy and, in particular, a higher carbon price. However, a drastic

carbon price increase might not be socially sustainable and the European

industry might not cope with that either. Moreover, some green

investments cannot be done by the private sector because of market

failures.

It is also crucial

to remove distortions in the taxation and subsidisation of the energy

system to incentivise more private investment. But the updated estimates3 of

Coady et al. (2019) show that they amounted to a mere 0.15% of GDP in

the EU in 2020. Eliminating explicit subsidies could cover about

one-fourth of the new public investment need.

Lessons from the past

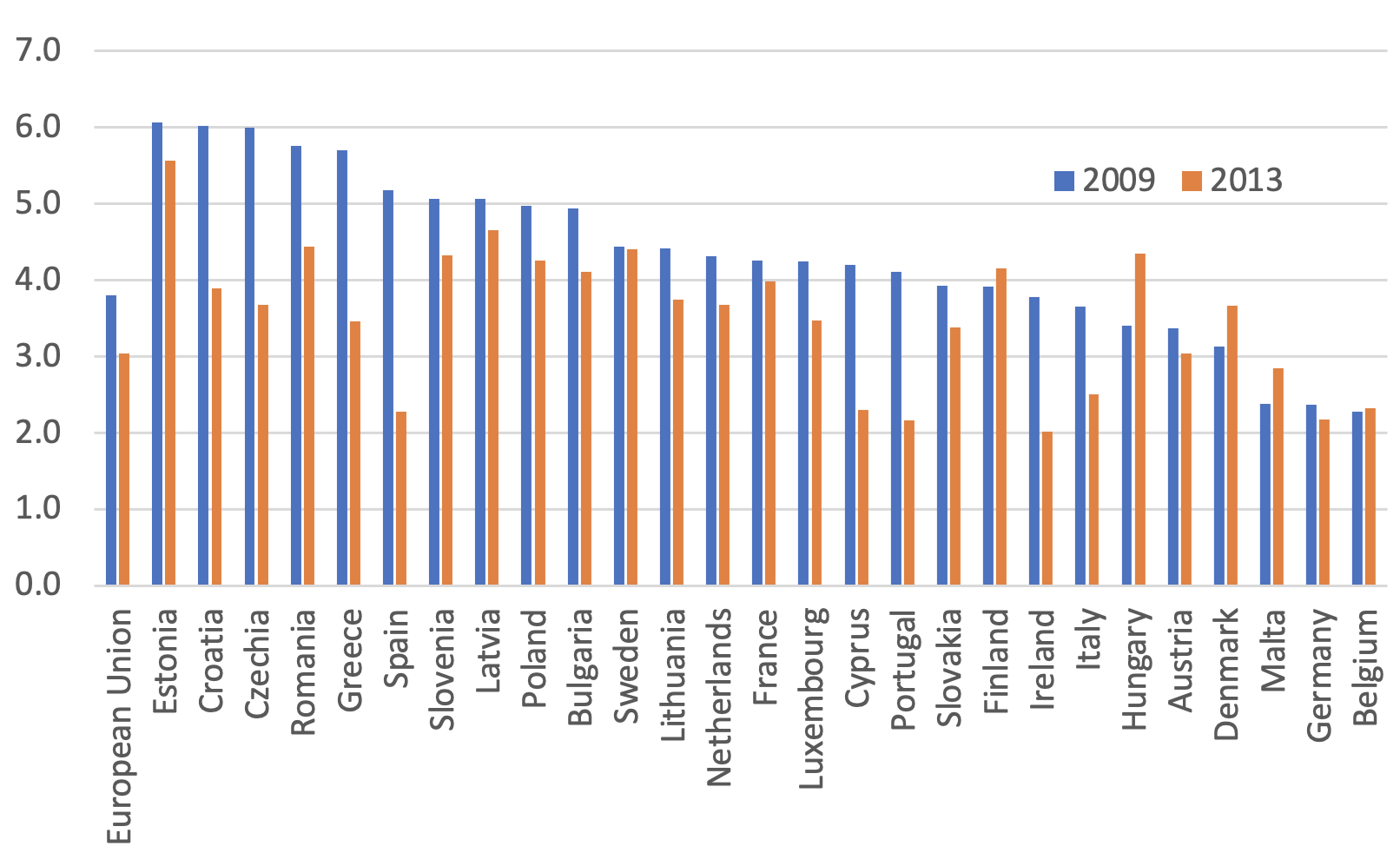

Public investment

was a victim of fiscal consolidation in previous episodes (Figure 1).

Gross public investment fell by 0.8 percentage points of GDP from 2009

to 2013 in the EU, and fell even further by 2016. Even in the group of

long-standing EU members that did not face market pressure, the real

value of public investment was slightly lower in 2013 than in 2009,

while overall primary expenditures increased by about 5% in this period.

There were only a few countries where public investment as a share of

GDP remained unchanged or increased (Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Hungary,

Sweden). In countries under market pressure, investment cut was more

dramatic. Other more future-oriented spending items, such as research

and development and education spending, were also cut.

Figure 1 Gross public investment, 2009 and 2013 (% GDP)

Source: November 2021 AMECO dataset.

There are reasons

why politicians prefer cutting investment over current spending. First,

in ageing societies, the interests of future generations have less

electoral support. Vote-maximising politicians are likely to decide

against the future, as seen in previous fiscal consolidation episodes.

Second, fiscal rules disadvantage investments by treating them fully as

current expenses, even though the benefits of investments accrue over

long periods. This biases the political economy further against

investment. Basic accounting logic would allow net investments to be

funded by deficits as they increase the stock of assets (Blanchard and

Giavazzi 2004).

Options for dealing with the trade-off between fiscal consolidation and increased green public investment

Fiscal consolidation

will have to start when EU fiscal rules are reinstated from 2023.

According to our simulations (Darvas and Wolff 2021), the speed of

consolidation can be moderate – half a percent per year – under a

flexible interpretation of current EU fiscal rules. This flexible

interpretation would neglect the 1/20th debt reduction rule (a rule that

de facto has not been implemented on account of other relevant factors

such as the implementation of structural reforms).

However, to increase

climate spending by 0.6% of GDP, governments would need to cut other

spending by 1.1 percentage points, so that the 0.5% overall

consolidation is achieved. Such deep cuts to non-climate spending simply

will not happen given our political systems.

Thus, policymakers

will face a hard choice between scaling back climate ambitions, amending

fiscal rules to make public climate investment possible, or designing a

new redistributive EU climate fund to circumvent fiscal rules. In our

view, climate targets must prevail, for two main reasons. First,

European backtracking on emission reduction targets might be followed by

similar backtracking in non-EU countries, which would risk irreversible

deterioration of the environment. Second, for most EU countries, there

is negligible risk of fiscal unsustainability. For these countries,

financing public climate investment by debt is sensible.

This leaves the EU

with three options for fostering green public investment. One would be a

general relaxation of EU fiscal rules. However, this would not provide

incentives to increase public investment, and additional fiscal

resources could well be used for recurrent consumptive spending given

the political economy reality.

A second option

would be to centrally fund all EU climate expenditure, possibly via EU

borrowing. In our simulations (Darvas and Wolff 2021), we show that this

is already the road undertaken for a number of southern and eastern EU

countries via the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RFF) until 2024. An

advantage of continuing with this approach and widening it to all EU

countries would be the approval of national green investment plans by

the Commission and the Council. This could help ensure consistency with

EU goals and prevent greenwashing. However, such a fund would need to

have a much larger capacity than NextGenerationEU (NGEU) and would need

to be in place for decades.

The treatment of the

RRF in EU fiscal indicators and fiscal rules provides lessons on how a

new EU climate fund would be treated. In line with the European System

of Accounts and a Council legal option, in September 2021, Eurostat4 concluded

that national spending financed by RRF grants will not be included in

national deficit and debt indicators, but spending financed by RRF loans

will be (Darvas 2022).

The justification

for excluding RRF grants is that EU borrowing to finance these grants

should not be counted as member-state debt because “there is no

match between the grants received from the RRF by the individual Member

States and the amounts that potentially will have to be repaid by each

individual Member State, as the two elements are calculated on the basis

of different criteria” and “there is great uncertainty on what amount each Member State will be liable for” (para. 38 of the Eurostat guidance). Thus, EU debt used to finance the grants constitutes only “a contingent liability for the Union budgetary planning”,

but not a national debt (para. 42). RRF grants do not matter for

deficits either. RRF grants are thus exempt from EU fiscal rules.

It is different for

spending financed by RRF loans. A country that borrowed from the EU is

liable to repay the full amount of the loan (along with its interest) to

the EU. Thus, spending financed by RRF loans is not exempt from fiscal

rules.

An EU climate fund

would be recorded the same way as the RRF. If it entailed major

cross-country redistribution, its political feasibility looks difficult.

Yet, without any re-distributive elements, spending by this fund would

not alleviate the constraint coming from fiscal consolidation

requirements.

The third option,

which we favour, would be a green golden rule: allowing green investment

to be funded by deficits that would not count in the fiscal rules. This

would provide incentives to undertake them, because such investment

would be excluded from the consolidation requirements. The critical

issue is the definition of green investment. A defining criterion of

climate investment should be a direct reduction of harmful emissions.

National fiscal councils and audit offices, the European Commission, the

European Court of Auditors, and the Council should play a role in

assessing compliance with the green golden rule.

A further advantage

of a green golden rule is that it could be utilised by all EU countries.

In contrast, a non-redistributive EU climate fund offering only loans

might not incur significant demand, partly because some EU countries can

borrow at a cheaper rate than the EU, and partly because demand for RRF

loans was also moderate, suggesting that borrowing from the EU is not a

popular action.

Contrary to public

investment, where the positive growth effects are well established in

the literature (e.g. Tenhofen et al. 2010), the impact of green

investment on growth is uncertain as many green investments would only

replace functioning ‘brown’ infrastructure. A green golden rule can

therefore be problematic in countries with debt sustainability problems.

Such countries should, initially, rely only on NGEU for their green

investment as they cannot ignore risks to budget constraints. Only after

NGEU expires after 2026 will the question of a green golden rule become

relevant for these countries.

Legal options

Ultimately, certain elements of the 2011 Six-Pack legislation5 and the 2012 Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance (TSCG)6 should

be revised to include a green golden rule in the EU fiscal framework.

This might take years. But until that is achieved, there are pragmatic

options for fostering such a rule in the preventive arm of the SGP,

though not in the corrective arm. This requires a revision of:

- the existing ‘investment clause’ to alter the adjustment path in the next years, and

- the medium-term objective (MTO) to change the long-run anchor for the structural balance.

A Council decision would be sufficient for these changes.

The current

investment clause allows for temporary deviations from the MTO (or from

the adjustment path towards it), amounting to at most 0.5% of GDP under

rather strict conditions, such that a negative GDP growth or a level of

GDP more than 1.5% below its potential. When all conditions are met,

only national co-financing of projects co-funded by the EU under certain

EU funds can be considered. The temporary deviation must be corrected

by the fourth year. These conditions are not specified in any EU

legislation, but are based on a Council decision, informed by a

Commission proposal,7 a Council legal service option and an EFC compromise agreement.8

Possible revisions

of the investment clause could include the removal of the GDP condition,

extending the scope to new green public investment, increasing the 0.5%

maximum deviation, and allowing a longer time to correct the temporary

deviation.

The determination of the MTO is codified in Article 2a of Regulation 1466/97,9 and

public investment is explicitly mentioned as a consideration for the

MTO. We propose that a first calculation of the MTOs follows the

procedure described in the latest (2017) version of the Code of Conduct

of the Stability and Growth Pact,10 and then in a second

step, these MTOs are lowered by the increase in the net green investment

the country aims to implement. Fiscal surveillance should ensure that

the extra fiscal space provided by a lowered MTO is solely used for net

green investment. A limitation of the proposed MTO correction is that

the floor of the MTO is minus 1% for euro-area and ERM2 members with

public debt below 60%, and minus 0.5% when debt is over 60% of GDP.

Conclusions

Increasing green

investments in periods of budget consolidation will prove politically

close to impossible if these investments are undertaken by cutting

current expenditures or raising taxes. It is also not recommended that

long-term capital investments be funded from current revenues. Instead,

economic and accounting logic suggests that net capital investments be

funded by deficits, reflecting the long lifetime of green

infrastructure. A green golden rule would provide the right incentives

for this. A major and justified worry is ‘greenwashing’, or the desire

of governments to declare current spending as green capital investments.

This needs to be addressed through a narrow definition of green

investments and strong institutional scrutiny. A second worry is that

green investments have uncertain growth effects. In countries with debt

sustainability concerns, such investments should therefore not be funded

with national deficits. And indeed, until 2026, it is the EU recovery

fund that will provide for that funding. Until a green golden rule is

agreed on and legally implemented, there is scope to allow for some of

such investment to take place by using the existing flexibilities.

References

Blanchard, O and F Giavazzi (2004) “Improving the SGP through a proper accounting of public investment”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 4220.

Coady, D, I Parry, N P Le and B Shang (2019), “Global Fossil Fuel Subsidies Remain Large: An Update Based on Country-Level Estimates”, IMF Working Paper 19/89.

Darvas, Z (2022), “A European climate fund or a green golden rule: not as different as they seem”, Bruegel Blog, 3 February.

Darvas Z and G Wolff (2021), “A Green Fiscal Pact: climate investment in times of budget consolidation” Bruegel Policy Contribution 18/2021.

D’Aprile, P, H Engel, G van Gendt et al .(2020), Net-zero Europe: Decarbonisation pathways and socioeconomic implications, McKinsey & Company.

European Commission (2020), Impact

assessment accompanying the document ‘Stepping up Europe’s 2030 climate

ambition. Investing in a climate-neutral future for the benefit of our

people’, SWD/2020/176 final.

International Energy Agency (2021), Net Zero by 2050. A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector.

Martin, P, J Pisani-Ferry and X Ragot (2021), “A new template for the European fiscal framework”, VoxEU.org, 26 May

Tenhofen, J, G Wolff

and K H Heppke-Falk (2010), “The Macroeconomic Effects of Exogenous

Fiscal Policy Shocks in Germany: A Disaggregated SVAR Analysis”, Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik 230(3): 328-355.

Endnotes

1 This column was written before the outbreak of the war in Ukraine.

2 The EIB (2021)

reported a 45% unweighted average public share in the EU. We calculate

the weighted average at 28%. IRENA’s (2021) 1.5°C scenario estimated a

22% public share at the global level in 2019, which would decline to 17%

beyond 2030.

3 https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/climate-change/energy-subsidies

4 https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/10186/10693286/GFS-guidance-note-statistical-recording-recovery-resilience-facility.pdf

5 https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/economic-and-fiscal-policy-coordination/eu-economic-governance-monitoring-prevention-correction/stability-and-growth-pact/legal-basis-stability-and-growth-pact_en

6 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:42012A0302(01)

7 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52015DC0012&from=EN

8 http://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-14345-2015-INIT/en/pdf

9 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:01997R1466-20111213

10 http://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-9344-2017-INIT/en/pdf

Senior Fellow, Bruegel; Senior Research Fellow, Corvinus University of Budapest

Vox

© VoxEU.org