his column surveys the drivers, policy approaches and technical designs,

based on a comprehensive and publicly available database. It finds that

all Central bank digital currency projects aim to complement cash

rather than replace it. Many projects would allow for an important role

of the private sector in the payment system.

Central

banks around the world are researching a new form of money: central bank

digital currency (CBDC). While the concept was proposed decades ago

(Tobin 1987), central banks were initially slow to embrace it. This has

changed with the declining use of cash – more so during the Covid-19

pandemic, the emergence of cryptocurrencies and the possible entry of

private ‘stablecoins’ (G7 Working Group on Stablecoins 2019, FSB 2020).1 CBDCs

could become a new, third form of central bank money, alongside

physical cash (accessible to the public) and central bank reserves

(accessible to many financial institutions).

National interest in

the topic differs, as do the policy approaches and technologies being

considered. Some central banks are experimenting with CBDCs, while

others have decided that they see no need. And even where CBDCs are

being studied, technological and economic designs differ, with very

different implications for the monetary and financial system (more on

this in a companion column to be published on Vox tomorrow).

In recent research

(Auer et al. 2020c), we analyse the economic and institutional drivers

of CBDC projects, thus shedding light on their motivations. We then

assess the policy approaches and technical design of projects, and

commonalities and differences across countries.

The drivers of CBDC developments: Assembling a new database

We assemble a comprehensive, publicly available database from three sources of information.2 First,

to measure the stance on issuance, we use the database of central bank

speeches maintained by the BIS. We search the universe of over 16,000

speeches for terms such as “CBDC” or “digital money”. We then classify

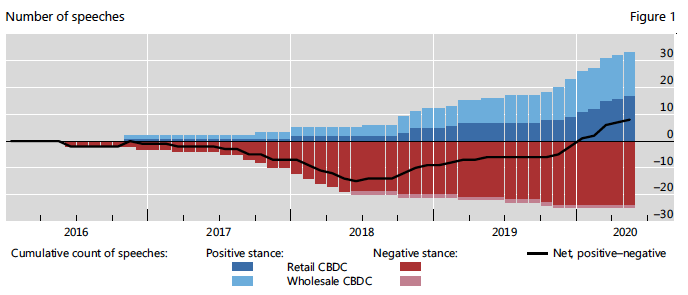

the stance as either negative, neutral, or positive.3 We differentiate the stance by wholesale and retail CBDC.4 The result is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Speeches on CBDCs have turned more positive since late 2018

Notes:

Search on keywords “CBDC”, “digital currency” and “digital money”. The

classification is based on the authors’ judgment. The score takes a

value of –1 if the speech stance was clearly negative or in case it was

explicitly said that there was no specific plan at present to issue

digital currencies. It takes a value of +1 if the speech stance was

clearly positive or a project/pilot was launched or was in the pipeline.

Other speeches (not displayed) have been classified as neutral.

Source: Auer et al. (2020c).

The second source is

published CBDC project reports and in-depth interviews we conducted

with the respective authors. Starting from the BIS-hosted list of

central bank webpages, we consult all published reports by central banks

on wholesale and retail CBDC projects. We only use official reports,

not rumours and unconfirmed press articles. We have classified these

into four buckets: no project, research, a pilot, or a live CBDC (at the

time of writing, hypothetical). A growing number of central banks has

communicated on their CBDC work, and several are actively piloting a

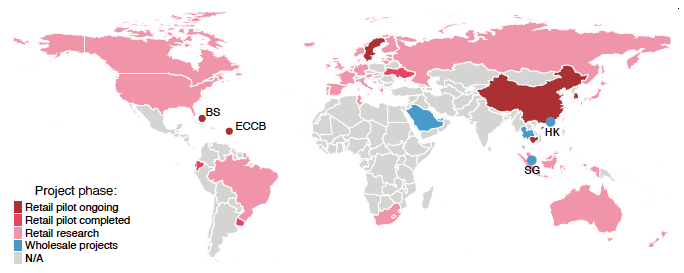

retail or wholesale CBDC (Figure 2).

Figure 2 CBDC projects status

Notes:

BS = The Bahamas; ECCB = Eastern Caribbean central bank; HK = Hong Kong

SAR; SG = Singapore. The use of this map does not constitute, and

should not be construed as constituting, an expression of a position by

the BIS regarding the legal status of, or sovereignty of any territory

or its authorities, to the delimitation of international frontiers and

boundaries and/or to the name and designation of any territory, city or

area.

Source: Auer et al. (2020c).

The third source is

internet search interest. In the paper, we use Google Trends and Baidu

trends to gauge the search intensity of keywords like “CBDC” for the

period 2013–20.

Stock-taking drivers and technical designs of CBDCs

We next look into

the drivers and commonalities. What do the countries with advanced CBDC

projects have in common? With regression analysis, we show that CBDC

projects are found more often in more digitised economies with a higher

capacity for innovation. In these economies, there may be higher demand

for new digital means of payment backed by the central bank. Other

things equal, work on retail CBDCs is also more common where the

informal or ‘shadow’ economy is larger. This may reflect greater

interest by these central banks in creating a ‘data trail’ for

transactions, and thus in promoting the use of digital payments.

We also find that

work on wholesale CBDCs is more advanced where there is higher financial

development. This may reflect the focus of wholesale CBDC projects on

increasing the efficiency of wholesale settlement in economies with deep

financial markets.

The technical

designs of CBDC can vary. This requires us to distil the main attributes

of different CBDC projects. One way to do so is the ‘CBDC pyramid’ of

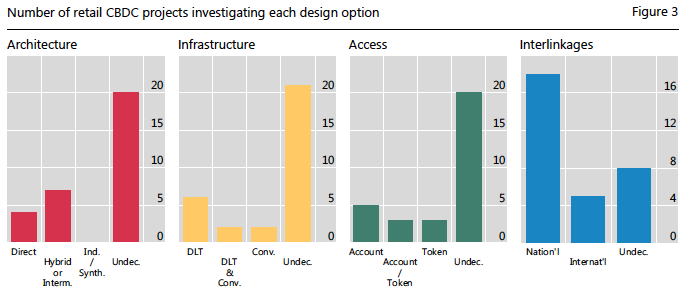

Auer and Böhme (2020).5 Figure 3 classifies the attributes of

ongoing retail CBDC projects. Among the retail CBDC projects in our

sample, we find a wide variety of approaches across jurisdictions to

architecture, infrastructure, access and cross-border (retail or

wholesale) interlinkages.

Figure 3 Attributes of retail CBDC projects

Notes:

Interm. = Intermediated; Ind. = Indirect; Synth. = Synthetic; Undec. =

undecided/unspecified or multiple options under consideration; DLT =

distributed ledger technology; Conv. = Conventional; Nation’l = national

use; Internat’l = international use.

Source: Auer et al. (2020c).

The first and foundational design choice is the architecture,

i.e. which operational role the central bank and private intermediaries

play in a CBDC. In the ‘Direct CDBC’ architecture, the central bank

directly operates the payment system, offers retail services directly,

and maintains the ledger of all transactions. In the ‘Hybrid CBDC’

architecture, the payment system can run on two engines: private sector

intermediaries handle retail payments, but the CBDC is a direct claim on

the central bank.6 In our stocktake, we find that four

central banks consider the Direct model (often with the goal to enhance

financial inclusion), seven are considering the Hybrid or Intermediated

options, and a larger group have not yet specified the architecture.7

The second technical design choice is the infrastructure.

This can be based on a conventional centralised database or on

distributed ledger technology (DLT). These technologies differ in their

efficiency and degree of protection from single points of failure. DLT

often aims to replace trust in intermediaries with trust in an

underlying technology. Yet no central bank we examined aims to rely on

permissionless DLT, as used for Bitcoin and many other private

cryptocurrencies. We find six central banks running prototypes on DLT,

two with conventional technology, and two considering both. Yet these

infrastructure choices are often for first proofs of concept and pilots.

Only time will tell if the same choices are made for large-scale

designs.

A third choice concerns how consumers can access

the CBDC. Account-based CBDCs are tied to an identity scheme, which can

serve as the basis for well-functioning payments with good law

enforcement. Yet access is likely to be difficult for one core target

group – the unbanked and individuals who rely on cash. This allows for

token-based payment options, for example pre-paid CBDC ‘banknotes’ that

can be exchanged both physically and digitally. Yet this also brings new

risks of illicit activity and counterfeiting. In our stocktake,

account-based access is more common, with five central banks clearly

leaning toward account-based, three toward token-based, and a further

three looking at both account and token-based access.

The fourth design choice is retail and wholesale interlinkages

in a CBDC’s design, including accessibility for cross-border payments.

Some designs may allow for use by non-residents. most of the projects in

our sample are for domestic use. Yet several – by the ECB, the French,

Spanish and Dutch central banks, and the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank –

are by construction focused on use among the members of a multi-country

currency area.

Case study: The People’s Bank of China’s e-CNY initiative

Among all CBDC projects, that of the People’s Bank of China (PBC) is perhaps the most advanced.8 Experimentation

with the e-CNY should be seen in the context of widespread use of

private digital payment services and a current mobile payments duopoly

of Alipay and WeChat Pay, together controlling 94% of the mobile

payments market.

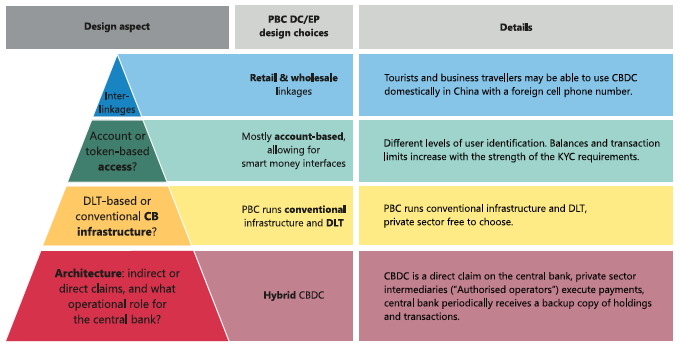

Figure 4 shows the

main design characteristics of the e-CNY, following the CBDC pyramid.

The architecture is squarely the ‘hybrid CBDC’ model – it is a direct

claim on the PBC, but on-boarding and real-time payment services are

operated by intermediaries (‘authorised operators’). The central bank

periodically receives and stores a copy of retail holdings and

transactions. The backbone of the infrastructure would be a mixed system

with conventional database and DLT. The PBC has, however, emphasised

that DLT is not yet sufficiently mature for such a large-scale

application.

Figure 4 Design characteristics of the PBC’s e-CNY project (pilot phase)

Source: Auer et al. (2020c).

Regarding access,

identity would be based on “loosely coupled account links”, such that

users could use e-CNY anonymously in daily transactions, but that “operating agencies should submit transaction data to the central bank via asynchronous transmission on a timely basis” (Fan 2020).9

The e-CNY would be

connected to existing retail and wholesale systems. The primary aim is

domestic retail use. Nonetheless, if an understanding can be reached

with foreign jurisdictions, non-residents (e.g. tourists and business

travellers who are physically in China) could access the e-CNY with a

foreign mobile phone number for an entry-level wallet.

Finally, if there is

a decision to go beyond the current pilot stage, the e-CNY will become a

complement to M0, which includes banknotes and coins, as well as

central bank depository accounts. It is not intended to fully replace

physical cash.

Conclusion: A new multitude of payments

The PBC pilot is

instructive for a model in which CBDC is a direct cash-like claim on the

central bank, but where the private sector handles all customer-facing

activity. This shows some commonalities, but also key differences with

work by the Riksbank, the Bank of Canada and other leading approaches we

review.

The diversity of

approaches and designs reflects that each central bank is considering a

CBDC that fits the unique needs of their own jurisdiction. Yet our

overview has also shown some key common features. In particular, none of

the designs we survey intends to replace cash; all aim to complement

it. Most projects would allow for an important role of the private

sector in the payment system. To encourage greater learning and allow

for future interoperability, ongoing dialogue and peer learning among

central banks remains important (e.g. CPMI and Markets Committee 2018,

Group of Central Banks 2020).

Authors’ note:

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily

reflect those of the Bank for International Settlements.

References

Auer, R and R Böhme (2020), “The technology of retail central bank digital currency”, BIS Quarterly Review, March: 85–100.

Auer, R, G Cornelli and J Frost (2020a), “Covid-19, cash and the future of payments”, BIS Bulletin 3, April.

Auer, R, J Frost, T

Lammer, T Rice and A Wadsworth (2020b), “Inclusive payments for the

post-pandemic world”, SUERF Policy Note 193.

Auer, R, G Cornelli

and J Frost (2020c), “Rise of the central bank digital currencies:

drivers, approaches and technologies”, CEPR Discussion Paper 15363.

Brunnermeier, M and D Niepelt (2019), “On the equivalence of private and public money”, Journal of Monetary Economics 106: 27-41.

Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI) and Markets Committee (2018), “Central bank digital currencies”, March.

Davoodalhosseini, S and F Rivadeneyra (2020), “A policy framework for e-money”, Canadian Public Policy 46(1): 94–106.

Fan, Y (2020), “Some thoughts on CBDC operations in China”, Central Banking, 1 April.

Fernández-Villaverde,

J, D Sanches, L Schilling and H Uhlig (2020), “Central bank digital

currency: central banking for all?” NBER Working Paper 26753.

Financial Stability Board (2020), “Regulation, Supervision and Oversight of “Global Stablecoin” Arrangements”, October.

G7 Working Group on Stablecoins (2019), “Investigating the impact of global stablecoins”, October.

Group of Central

Banks (2020), “Central bank digital currencies: foundational principles

and core features”, first report in a series of collaborations from a

group of central banks, October.

Keister, T and D Sanches (2019), “Should central banks issue digital currency?”, mimeo.

Tobin, J (1987), “The case for preserving regulatory distinctions”, Proceedings of the Economic Policy Symposium, Jackson Hole, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, pp 167–83.

Endnotes

1 In the Covid-19

pandemic, attention to CBDCs has been enhanced due to concerns about

viral transmission through cash (see Auer et al. (2020a)) and the need

for remote payments and pandemic-related government-to-person payments

that reach the whole population (see Auer et al. (2020b)).

2 The database is available online at https://www.bis.org/publ/work880.htm

3 This is based on

authors’ judgement. A negative stance is when the speech was clearly

negative toward CBDCs or explicitly said there was no plan to issue

CBDCs. A positive stance is when speeches are clearly positive or said

that a pilot or project was in the pipeline.

4 So-called

wholesale CBDCs could become a new instrument for settlement between

financial institutions. Retail (or general purpose) CBDCs would be

cash-like central bank accessible to all. The issuance of CBDCs would be

a far-reaching step, and many open questions remain.

5 The pyramid gives a

taxonomy of technical designs, starting from consumer needs. The scheme

of design choices forms a hierarchy in which the lower, initial layers

represent design decisions that feed into subsequent, higher-level

decisions.

6 The Hybrid CBDC

comes in two variants: the central bank can either keeps a central

ledger of all transactions, which allows it to restart payments, or it

can maintains only a wholesale ledger (the ‘Intermediated’ variant).

7 We also examine

whether central banks pursue the so-called synthetic or indirect CBDC

model. The latter involves claims on private sector intermediaries that

are fully backed by central bank reserves. However, at current, no

public report indicates that a central bank is pursuing this

indirect/synthetic architecture.

8 CBDC development

efforts in China go back to at least 2014. In late 2019, the PBC

announced it would conduct a pilot study for a retail CBDC, the Digital

Currency and Electronic Payment (DC/EP) project. On 20 April 2020, a PBC

spokesperson confirmed that pilot testing was under way in several

cities: Shenzhen, Suzhou, Chengdu, Xiong'an and the “2022 Winter

Olympics Office Area” in Beijing. Recently, PBC has noted that the

project has been renamed to e-CNY, with CNY standing for Chinese Yuan or

renminbi.

9 This would ensure

that users remain anonymous to each other, but allow the central bank

“to keep track of necessary data to implement prudent regulation and

crack down on money laundering and other criminal offences, as well as

easing the workload for commercial banks” (Fan 2020).