The European Union’s proposed Digital Markets Act will attempt to control online gatekeepers by subjecting them to a wider range of upfront constraints.

Digital

market forces drive huge efficiency gains. But they also create

winner-take-all dynamics that can, left unchecked, lead to monopolistic

markets and hurt consumers in the long-run. Slow-moving competition

policy tools are ill-equipped to fully address these digital concerns.

(1) The DMA was proposed alongside the

Digital Services Act (DSA) which targets illegal goods, services and

content, abuse of platforms, advertising and algorithmic transparency.

The DSA concerns most online businesses.

In December 2020 the European Commission

proposed the Digital Markets Act (DMA) to regulate the gatekeepers of

the digital world by imposing direct restrictions on the behaviour of

tech giants (1). While the Commission has not named any companies, it

has proposed criteria that are sure to catch Google, Facebook, Amazon,

Apple, Microsoft and SAP, among others.

This blog unpacks the different provisions of the DMA and explains why the Commission chose to regulate big tech.

What is a digital gatekeeper?

A gatekeeper is a company that acts as an

important nexus between two or more groups of users – say buyers and

sellers. When they attract a large share of users on one side of the

platform (say buyers) gatekeepers can become unavoidable tolls on routes

to certain markets or customers. Users on the other side of the

platform (say sellers) may have little choice but to use the

gatekeepers’ infrastructure.

The EU has thought in terms of ‘digital gatekeeper’ for as long as Google has existed.

In the DMA, it defines a gatekeeper as a platform that operates in one

(or more) of the digital world’s eight core services (including search,

social networking, advertising and marketplaces) in at least three EU

countries and:

- Has a significant impact on the internal market (defined

quantitatively as an annual turnover of €6.5 billion or a market

capitalisation of €65 billion);

- Serves as an important gateway for business users to reach end-users

(user base larger than 45 million monthly end-users and 10,000 business

users yearly); and

- Enjoys an entrenched and durable position or is likely to continue

to enjoy such a position (meets the first and second criteria over three

consecutive years).

A platform that meets these quantitative

thresholds is labelled a gatekeeper. However, the Commission would

retain the right to remove (or confer) ‘gatekeeper’ status by

qualitative assessment. The Commission would also be empowered to alter

the thresholds as technologies change, and to conduct market

investigations to look for new gatekeepers.

Why big tech is big

Digital hubs are a time drain. In December 2019 (pre-COVID-19), the average Italian

spent 45 hours a month on Facebook, and 24 hours on Google. The same

may be true for physical marketplaces and social venues, but online, the

hubs are controlled by only a handful of global players. British

internet users spend 40%

of their online time on sites owned by just two providers (Google and

Facebook). These same two providers are frequented by 96% and 87% of

British users each month. 58% of Germans book their holidays through just one site (Booking.com).

For a long time, policymakers were not

especially worried about high concentration in digital markets. They

assumed digital champions faced competition ‘for the market’, that is,

competition from outside players keen on becoming tomorrow’s winners.

After all, Facebook outcompeted MySpace. Google overtook AltaVista.

Nokia once looked unassailable.

But the competitive dynamics of the early

days of the internet no longer seem to apply. While the primacy of

AltaVista lasted one year (and Myspace three years), a decade

of that of Google and Facebook has now passed. The persistence of

today’s digital leaders has become concerning: have they found a way out

of the competitive race?

There are several explanations for the

unusual persistence of digital leadership. For one, digital markets

feature characteristics of ‘tipping markets’, or markets in which there

is room for only a few players. These characteristics are the

combination of:

- Consumer inertia (why bother shop for a new email provider when the current one works just fine?);

- Increasing returns to scale (recommendation algorithms become better with more users);

- Low marginal costs (it costs close to nothing to distribute one extra app);

- Strong direct and indirect network effects (the more users frequent a

social media site, the more attractive it becomes to other users and to

advertisers).

To illustrate, consider the market for

mobile operating systems (OS). OS with more end-users are naturally more

attractive to app developers than OS with fewer end-users. Developers

thus tend to prioritise the largest OS (an example of indirect network

effects). Over time, the gap in what larger and smaller OS can offer

grows. The large OS gather more user data which helps them improve the

quality of their recommendations. The small OS become even less

attractive, until they go bust and the winners take all. One of the

reasons Microsoft abandoned the mobile market in 2017 is that it could not attract enough app makers to its OS.

Masses of data, cheap machine learning technologies and the refining of ecosystem business models have

further entrenched leading positions, conferring incredible bargaining

power to set commercial conditions and terms unilaterally (eg to expel,

charge high fees, manipulate rankings and control reputations). Such

power leaves platform users vulnerable to abuse.

Online gatekeepers are a source of concern

Success is by no means illegal. But

practices that lock it in might well become unlawful. The DMA would

constrain gatekeepers’ behaviour while forcing them to proactively open

up to more competition. Those in breach of the rules face penalties of

up to 10% of their yearly turnover and repeat offenders face being

broken-up. The DMA addresses two problems: high barriers to entry and

anticompetitive practices by gatekeepers. The objective is to make

digital markets both contestable and fair for existing and future

rivals.

To illustrate, consider the DMA’s

prohibition on combining end-user data from different sources without

consent. Combining data from multiple sources can give gatekeepers a

significant advantage over smaller rivals. Indeed, data gleaned from one

source, say online searches, can be used to predict users’ preferences

in other market, say music streaming. A gatekeeper that knows the web

browsing history of a user is much better positioned to predict her

musical tastes than a data-poor rival. Restricting the combination of

data from multiple sources, therefore, restricts the ability of

gatekeepers to leverage their market power from one market to another to

the detriment of small players.

Other prominent rules include:

- No self-preferencing: a prohibition on ranking their own products over others;

- Data portability: an obligation to facilitate the portability of continuous and real-time data;

- No ‘spying’: a prohibition on gatekeepers on using the data of their business users to compete with them;

- Interoperability of ancillary services: an obligation to allow

third-party ancillary service providers (eg payment providers) to run on

their platforms;

- Open software: an obligation to permit third-party app stores and software to operate on their OS.

The proposal also includes a requirement

that gatekeepers inform the regulator of all mergers and acquisitions,

even when the target is too small to be subject to merger control. It

does not include any powers to intervene to block these mergers however

(unlike the equivalent UK proposal).

As with the definition of ‘gatekeeper’,

the DMA’s list of obligations is a balancing act between enforceability

and flexibility. Indeed, while seven rules apply equally to all

gatekeepers, the majority (eleven rules) will be tailored to each.

The practical consequences of unconstrained power

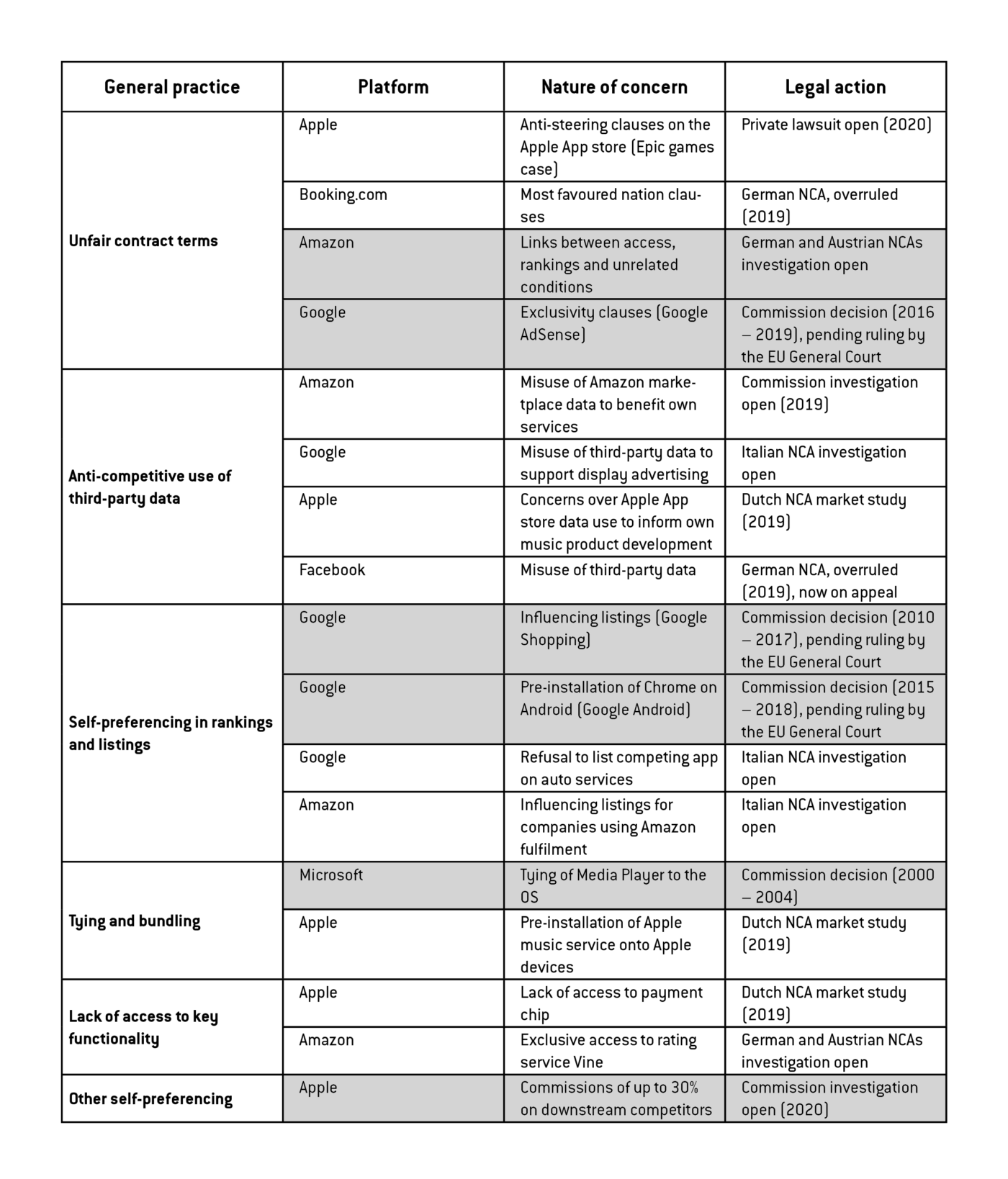

In the last few years, numerous studies (twenty-two of which are summarised here)

and antitrust investigations have suggested that some gatekeepers

adopted questionable practices from a competition standpoint (Table 1).

In setting the DMA list of obligations,

the Commission drew on the knowledge it acquired through the various

antitrust investigations: the DMA rulebook targets most of the unfair

practices listed in Table 1. Take the Amazon case for example. The

Commission suspects the e-retailer of gathering data on the activities

of third-party sellers in order to outcompete them. One DMA obligation –

for gatekeepers not to use the data of business users to compete with

them – would clearly addresses the problematic practice.

Table 1: Alleged unfair practices by large digital platforms investigated by EU or national competition authorities (NCA)

Source: Bruegel based on European Commission’s DMA Impact Assessment (2020). Note: Cases investigated by the European Commission are highlighted in grey.

Stepping-up with ex-ante regulation

The DMA takes a diametrically opposite

approach to antitrust enforcement (which is currently the United States’

favoured approach). It is an ex-ante set of rules that constrains operators before any bad behaviour can materialise, as opposed to antitrust which kicks in after an infringement (ex-post).

Antitrust (ex-post) enforcement

has a number of advantages: by proceeding on a case-by-case basis it can

be applied to a variety of business models, avoiding the imprecision of

regulation. However examples like the Google shopping case, now in its

tenth year, show that this approach isn’t fit for digital markets.

Google’s business model has changed considerably over the past decade,

aside from the fact that for the competitors hurt by Google’s conduct in

2010, the damage has been done. In fast-moving markets prone to

tipping, ten years is a lifetime. On average, successful start-ups that

reach a valuation of $1 billion do so in one year less than it takes the

Commission to run an investigation into large digital platforms (Figure

1).

The analytical pillars of antitrust cases

are: market definition (eg the market for music streaming) and

assessment of market dominance (ie how much power the investigated firm

has in said market). As highlighted in the DMA’s impact assessment,

both are notoriously difficult to establish in multisided digital

markets: what may amount to a market on one side of the platform (eg the

side of music streamers) may not clearly extend as a market on the

other (eg the side of music publishers). The fact that many digital

goods are provided for free also challenges traditional methods for

assessing market power. The EU’s competition authority’s resources are already stretched: this can only exacerbate the great asymmetries in technology and knowledge between the authorities and market players.

Even if competition enforcement could

somehow be sped up in digital cases, it would fail to adequately address

the systemic failures that stem from the behaviour of digital users,

for example the tendency to stick to the default option. Online

platforms have developed sophisticated tools to monitor users’ behaviour

in real-time and are uniquely positioned to leverage behavioural biases

to solidify their market positions. Consider, for instance, that on a

smartphone where Google is the default search browser, 97% of searches

are made on Google versus 86% on desktops where Bing is the default,

according to a CMA report. Forcing one platform to change its default setting will do little to prevent every other digital player from doing the same.

Regulation can address some of these

limitations: by setting out clear rules from the outset, regulators

would be empowered to act quickly when these rules are violated. The

creation of a digital market centre of knowledge and expertise would

ensure speedy detection. Regulation is also more far-reaching: it

concerns all gatekeepers, all of the time.

True, regulation is more prone to capture

by industry than competition policy. Over-enforcement is also a concern

as rules could fail to account for consumer benefits from seemingly

anti-competitive behaviour. In a very dynamic environment, regulation

can be rendered useless.

These are risks EU policymakers are

willing to take after what they have judged to be years of

underenforcement. And the proposed DMA offers more flexibility than the

stereotypically-rigid regulatory approach. As described above, the terms

of the DMA would evolve alongside markets and adapt to individual

business models. More fundamentally, the aim of the DMA is to protect

the competitive process, not to prescribe specific outcomes. The

Commission does not propose to regulate big tech as natural monopolists,

but rather to make sure it never has to.

Bruegel

© Bruegel

Key

Hover over the blue highlighted

text to view the acronym meaning

Hover

over these icons for more information

Comments:

No Comments for this Article