Central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) offer in digital form the unique advantages of central bank money: settlement finality, liquidity and integrity. They are an advanced representation of money for the digital economy.

- Digital money should be designed with the

public interest in mind. Like the latest generation of instant retail

payment systems, retail CBDCs could ensure open payment platforms and a

competitive level playing field that is conducive to innovation.

- The ultimate benefits of adopting a new

payment technology will depend on the competitive structure of the

underlying payment system and data governance arrangements. The same

technology that can encourage a virtuous circle of greater access, lower

costs and better services might equally induce a vicious circle of data

silos, market power and anti-competitive practices. CBDCs and open

platforms are the most conducive to a virtuous circle.

- CBDCs built on digital identification

could improve cross-border payments, and limit the risks of currency

substitution. Multi-CBDC arrangements could surmount the hurdles of

sharing digital IDs across borders, but will require international

cooperation.

Introduction

Digital innovation has wrought far-reaching changes in all sectors of

the economy. Alongside a broader trend towards greater digitalisation, a

wave of innovation in consumer payments has placed money and payment

services at the vanguard of this development. An essential by-product of

the digital economy is the huge volume of personal data that are

collected and processed as an input into business activity. This raises

issues of data governance, consumer protection and anti-competitive

practices arising from data silos.

This chapter examines how central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) can

contribute to an open, safe and competitive monetary system that

supports innovation and serves the public interest. CBDCs are a form of

digital money, denominated in the national unit of account, which is a

direct liability of the central bank.1

CBDCs can be designed for use either among financial intermediaries

only (ie wholesale CBDCs), or by the wider economy (ie retail CBDCs).

The chapter sets out the unique features of CBDCs, asking what their

issuance would mean for users, financial intermediaries, central banks

and the international monetary system. It presents the design choices

and the associated implications for data governance and privacy in the

digital economy. The chapter also outlines how CBDCs compare with the

latest generation of retail fast payment systems (FPS, see glossary).2

To set the stage, the first section discusses the public interest

case for digital money. The second section lays out the unique

properties of CBDCs as an advanced representation of central bank money,

focusing on their role as a means of payment and comparing them with

cash and the latest generation of retail FPS. The third section

discusses the appropriate division of labour between the central bank

and the private sector in payments and financial intermediation, and the

associated CBDC design considerations. The fourth section explores the

principles behind design choices on digital identification and user

privacy. The fifth section discusses the international dimension of

CBDCs, including the opportunities for improving cross-border payments

and the role of international cooperation.

Money in the digital era

Throughout the long arc of history, money and its institutional

foundations have evolved in parallel with the technology available. Many

recent payment innovations have built on improvements to underlying

infrastructures that have been many years in the making. Central banks

around the world have instituted real-time gross settlement (RTGS)

systems over the past decades. A growing number of jurisdictions (over

55 at the time of writing)3

have introduced retail FPS, which allow instant settlement of payments

between households and businesses around the clock. FPS also support a

vibrant ecosystem of private bank and non-bank payment service providers

(PSPs, see glossary).

Examples of FPS include TIPS in the euro area, the Unified Payments

Interface (UPI) in India, PIX in Brazil, CoDi in Mexico and the FedNow

proposal in the United States, among many others. These developments

show how innovation can thrive on the basis of sound money provided by

central banks.

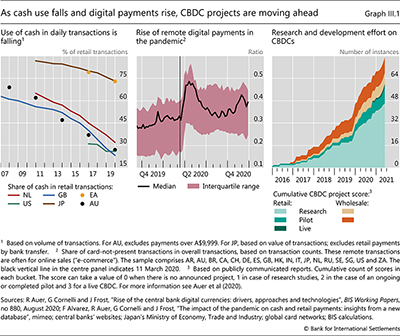

Yet further-reaching changes to the existing monetary system are

burgeoning. Demands on retail payments are changing, with fewer cash

transactions and a shift towards digital payments, in particular since

the start of the Covid-19 pandemic (Graph III 1,

left-hand and centre panels). In addition to incremental improvements,

many central banks are actively engaged in work on CBDCs as an advanced

representation of central bank money for the digital economy. CBDCs may

give further impetus to innovations that promote the efficiency,

convenience and safety of the payment system. While CBDC projects and

pilots have been under way since 2014, efforts have recently shifted

into higher gear (Graph III.1, right-hand panel).

The overriding criterion when evaluating a change to something as

central as the monetary system should be whether it serves the public

interest. Here, the public interest should be taken broadly to encompass

not only the economic benefits flowing from a competitive market

structure, but also the quality of governance arrangements and basic

rights, such as the right to data privacy.

It is in this context that the exploration of CBDCs provides an

opportunity to review and reaffirm the public interest case for digital

money. The monetary system is a public good that permeates people's

everyday lives and underpins the economy. Technological development in

money and payments could bring wide benefits, but the ultimate

consequences for the well-being of individuals in society depend on the

market structure and governance arrangements that underpin it. The same

technology could encourage either a virtuous circle of equal access,

greater competition and innovation, or it could foment a vicious circle

of entrenched market power and data concentration. The outcome will

depend on the rules governing the payment system and whether these will

result in open payment platforms and a competitive level playing field.

DC

DC projects are moving ahead" border="0">

Central bank interest in CBDCs comes at a critical time. Several

recent developments have placed a number of potential innovations

involving digital currencies high on the agenda. The first of these is

the growing attention received by Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies;

the second is the debate on stablecoins; and the third is the entry of

large technology firms (big techs) into payment services and financial

services more generally.

By now, it is clear that cryptocurrencies are speculative assets

rather than money, and in many cases are used to facilitate money

laundering, ransomware attacks and other financial crimes.4 Bitcoin in particular has few redeeming public interest attributes when also considering its wasteful energy footprint.5

Stablecoins attempt to import credibility by being backed by real

currencies. As such, these are only as good as the governance behind the

promise of the backing.6

They also have the potential to fragment the liquidity of the monetary

system and detract from the role of money as a coordination device. In

any case, to the extent that the purported backing involves conventional

money, stablecoins are ultimately only an appendage to the conventional

monetary system and not a game changer.

Perhaps the most significant recent development has been the entry of

big techs into financial services. Their business model rests on the

direct interactions of users, as well as the data that are an essential

by-product of these interactions. As big techs make inroads into

financial services, the user data in their existing businesses in

e-commerce, messaging, social media or search give them a competitive

edge through strong network effects. The more users flock to a

particular platform, the more attractive it is for a new user to join

that same network, leading to a "data-network-activities" or "DNA" loop

(see glossary). ...

more at BIS

© BIS - Bank for International Settlements

Key

Hover over the blue highlighted

text to view the acronym meaning

Hover

over these icons for more information

Comments:

No Comments for this Article