This column provides a comprehensive taxonomy for categorising central

bank digital currency design options, and evaluates these options based

on their allocative efficiency and attractiveness for users. The

analysis shows that digital cash substitutes cannot be justified from

either perspective. Instead, there is huge potential for central bank

digital currencies in a retail payment system organised by the central

bank, but without a new, independent payment object.

The discussion about central bank digital currency (CBDC)

has gained an impressive momentum. Auer et al. (2020) report that many

central banks have published retail or wholesale CBDC work and that in

speeches of central bank governors and board members about CBDC there

have now been more speeches with a positive than a negative stance. The

ECB has recently published a comprehensive report on ‘a digital euro’

(ECB 2020).

These activities have led to a growing literature, with a focus on

the macroeconomic dimensions of CBDCs. Key topics are the effects of

CBDCs on commercial banks, especially the risk of disintermediation, and

on monetary policy and financial stability (Carapella and Flemming

2020, Brunnermeier and Niepelt 2019, Fernández-Villaverde et al. 2020,

Andolfatto 2018).

In contrast, the microeconomic aspects of CBDCs have received

relatively little attention. Our study (Bofinger and Haas 2020) provides

a microeconomic analysis of CBDC, which in our view is of central

importance for a comprehensive discussion of CBDCs. Specifically, two

questions are at stake:

- What is the market failure that would justify central banks

entering business areas that have so far been operated by commercial

banks and private retail payment system providers?

- Are the options discussed so far by central banks attractive enough

for CBDCs to compete successfully with the products offered by private

providers?

Finally, the microeconomic analysis shows that there is no such

thing as a CBDC per se, but rather a variety of different design

options. Therefore, a macroeconomic analysis can only make sense if we

have first clarified what we mean by CBDC.

CBDC design options

A systemic perspective is required for a comprehensive taxonomy of

CBDC design options. From the systemic perspective, CBDC concepts can be

presented in two separate but interrelated ways. CBDCs can be discussed

from the perspective of:

- new payment or settlement objects made available by central banks, and/or

- new payment infrastructures or systems operated by central banks.

A CBDC can thus be understood as a purely monetary object, i.e. a

deposit with the central bank that is used within the framework of

existing real-time gross settlement (RTGS) payment systems. However, it

can also be understood as an independent payment system that operates in

parallel to the existing system using deposits held with the central

bank. The systemic perspective also opens the view for solutions where

central banks create new retail payment systems which would not

necessarily require deposits that are held with central banks.

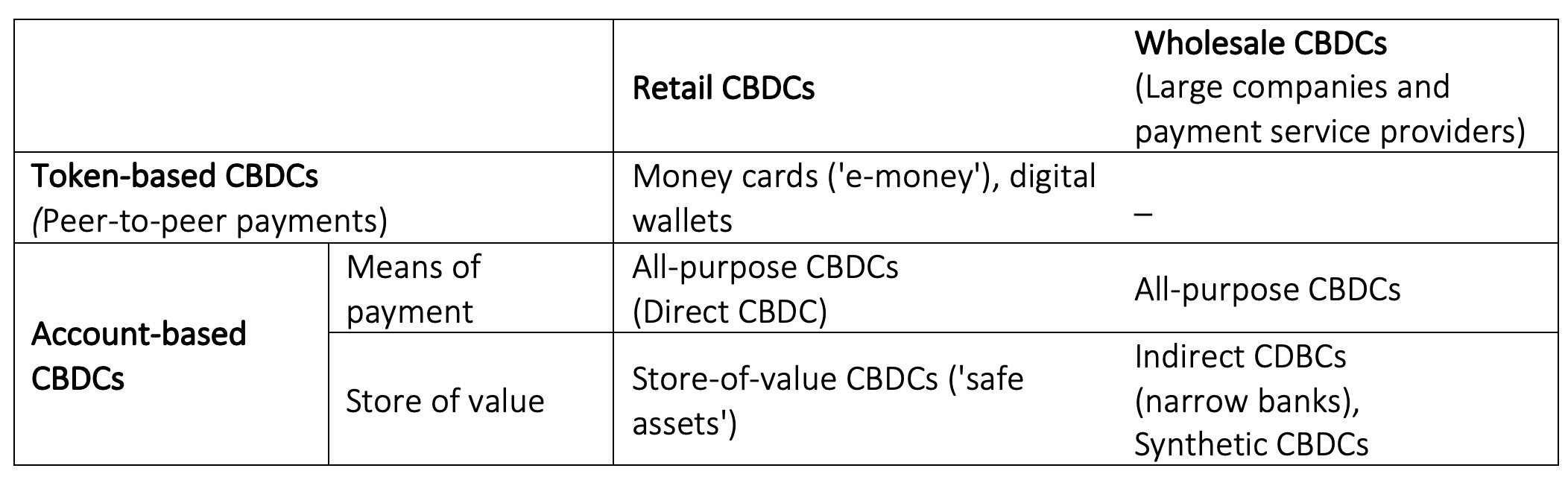

Table 1 Options for digital central bank projects

A further differentiation arises in the case of CBDC objects. Here, a

distinction must be made between account-based and token-based CBDCs.

In addition, one can also differentiate between central bank balances,

which can be used primarily as a means of payment, and balances which

can be used primarily as a store of value. Finally, one can

differentiate between retail CBDCs designed for private households and

wholesale CBDCs designed for firms or for payment service providers.

Table 2 Options for CBDC objects

Evaluation

For our microeconomic evaluation of CBDC design options we use two criteria:

- Allocative efficiency: Any government

interference with the market process requires the diagnosis of market

failure (Carletti et al. 2020). The burden of proof lies with the

central banks. They have to show that the objectives which they pursue

with CBDCs are currently not satisfactorily met by the private

providers. And even if public goods like financial stability or

stability of the payment system are not optimally met, it is not obvious

that CBDC is the adequate solution.

- Attractiveness for users: If CBDCs are designed as

new payment objects that are used within existing payment systems, the

user perspective implies that CBDCs must compete with existing payment

objects (above all cash and traditional bank deposits). If CBDCs

constitute new payment systems, their acceptance by private users must

be analysed within the context of the existing payments ecosystem. For

the reputation and credibility of central banks, it is important that

any CBDC solution is attractive enough for potential users to adopt it.

A narrow CBDC approach is the provision of CBDC objects as means

of payment that are used within the existing payment systems, above all

the real-time gross settlement systems operated by central banks. As

the model by Bindseil (2020) shows, account-based CBDCs can be designed

in a way that they are mainly suitable as a payment object. But from the

allocative perspective there is no obvious market failure that could

justify the provision of an ordinary bank deposit by a central bank.

From a user perspective, having a direct account with the central bank

could be attractive because of its absolute safety. But as bank deposits

below €100,000 are protected by the deposit insurance schemes, holding

smaller amounts of CBDCs – Bindseil (2020) speaks of a limit of €3,000 –

is not an obvious reason to switch from a traditional bank account to a

central bank account. In addition, it is unlikely that central banks

would be able to offer the same spectrum of services that are associated

with a private bank account. And if they decided to do so, this

interference with private banks could hardly be justified by a market

failure.

The case for a token-based CBDC that could serve as a digital

substitute for cash is also not obvious. While the allocative

perspective could justify that central banks provide a digital

substitute for cash for which they already have a monopoly, the need to

comply with anti-money laundering (AML) regulations sets rigid

quantitative limitations for such products. Accordingly, from a user

perspective the demand for a token CBDC will be very low as they would

only provide an imperfect substitute for cash, which today is especially

attractive for payments in the shadow economy and as a store value in

periods of financial instability.

An option that has received little attention so far is a CBDC that is

designed solely as a store of value. Such a CBDC could only be used for

payments to and from the commercial bank account of its holder. From

the allocative perspective, the supply of such a CBDC could be justified

by the need of (nominally) safe assets which can only be provided by

central banks. The demand for a store-of-value CBDC would come from

firms and large investors with bank deposits of more than €100,000,

which would be bailed-in in the case of a bank restructuring. From the

user perspective, this demand would depend on the interest rate for such

deposits. Central banks could auction store-of-value deposits which

would give them a perfect control over their amount. While there could

be a high demand for such a CBDC, central banks do not seem to be

interested in this option, as they fear that this could lead to a strong

disintermediation of the banking system (Bindseil 2020).

Store-of-value CBDCs could also be designed as collateral for large

payment service providers. In China, Alipay is required to hold deposits

with the central bank. Libra/Diem (2020, p.11) has expressed the “hope

(…) that as central banks develop central bank digital currencies

(CBDCs), these CBDCs could be directly integrated with the Libra

network, removing the need for Libra Networks to manage the associated

Reserves (…)”. This approach would prevent the Libra/Diem system from

getting disconnected from central banks and their control over the

monetary system. From an allocative perspective, such central bank

intervention can be justified as it would de facto include payment

service providers under the umbrella of the central bank’s reserve

requirements and hence improve financial stability.

More ambitious CBDC models, like the Swedish e-krona (Sveriges

Riksbank 2018), envisage a stand-alone payment system within which new

CBDC objects can be transferred. For the attractiveness of CBDC bank

deposits this is not necessarily an advantage. Without a specific

payment system, CBDC deposits could be used like a commercial bank

deposit. With a stand-alone payment system, CBDC deposits could only be

used for payments to other CBDC accounts. The lack of interoperability

constitutes a major drawback of such CBDC solutions. Especially in a

small country like Sweden, the domestic focus is another major

disadvantage.

Therefore, if central banks want to develop a serious answer to the

dynamic activities of global payment service providers, they must

rethink their whole approach to CBDCs. The benchmark is set by PayPal

which is the ‘elephant in the room’ of global payments. It shows that

instead of national schemes that can only operate with the national

currency and can only make transactions with system-specific accounts,

the solution must be supranational with a multicurrency operability and

an openness to payment objects that are not system-specific.

But even if central banks realise that their task is not to develop a

digital substitute for cash but a digital alternative for global

payment systems, it will not be easy to achieve the high level of

sophistication and the broad spectrum of services, especially for

e-commerce, of such payment systems. But in contrast to narrow CBDC

models, from an allocative point of view there would be an obvious

justification for supranational retail payment networks operated by

central banks.

In sum, we argue that there is no obvious justification for digital

cash substitutes from the point of view of allocative efficiency. In

addition, from a user perspective, the narrow solutions that are

discussed by central banks so far do not seem attractive enough to

compete successfully with private bank deposits and private retail

payment systems like PayPal. The key advantage of CBDC, its absolute

safety, is irrelevant for retail payments. These findings mainly concern

advanced countries with a large share of the population having access

to bank accounts. For emerging and developing economies, such CBDC

solutions could be a suitable tool to approach the problem of a large

share of people without access to bank accounts.

However, there is a huge potential for CBDCs as a store of value for

retail payment service providers, like Libra/Diem. Astonishingly,

central banks have so far not discussed this option, although it would

help them to maintain control over private retail payment networks

outside the existing bank-based payment system that relies on central

bank reserves and the existing central bank settlement systems.

Finally, a clear market failure can be identified for global retail

payment networks which are based on monopolistic or oligopolistic

structures. However, the central banks' response would then have to be

supranational rather than national. Moreover, successful networks such

as PayPal show that such systems are not tied to a system-specific

currency or system-specific payment objects.

Thus, if central banks stick to their current approach, the risk is

high that CBDCs will become a gigantic flop. This would be anything but

beneficial for the reputation of central banks.

References

Andolfatto, D (2018), "Assessing the impact of central bank digital

currency on private banks", FRB St. Louis Working Paper 2018-26b.

Auer, R, G Cornelli and J Frost (2020), "Rise of the central bank

digital currencies: drivers, approaches and technologies", BIS Working

Papers, August, No. 880.

Bindseil, U (2020), "Tiered CBDC and the financial system", ECB Working Paper Series, January, No. 2351.

Bofinger, P and T Haas (2020), "CBDC: Can central banks succeed in the marketplace for digital monies?", CEPR Discussion Paper No 15489.

Brunnermeier, M K and D Niepelt (2019), "On the equivalence of private and public money", Journal of Monetary Economics 106: 27-41.

Carapella, F and J Flemming (2020), "Central Bank Digital Currency: A Literature Review", FEDS Notes, Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 9 November.

Carletti, E, S Claessens, A Fatás and X Vives (2020), The Bank Business Model in the Post-Covid-19 World, The Future of Banking 2, CEPR Press, 18 June.

European Central Bank (2020), "Report on a digital euro", 2 October.

Fernández-Villaverde, J, D Sanches, L Schilling and H Uhlig (2020),

"Central Bank Digital Currency: Central Banking For All?", NBER Working

Paper Series No 26753.

Kumhof, M and C Noone (2018), "Central bank digital currencies —

design principles and balance sheet implications", Bank of England Staff

Working Paper, May, No. 725.

Libra/Diem Association (2020), “Cover Letter – White Paper V2.0”, April.

Sveriges Riksbank (2018), "The Riksbank’s e-krona project - Report 2", October.