Some countries have issued their own central bank digital currencies, and many European economists favour such a currency too. This column shows that when properly designed, central bank digital currencies can help stabilise the financial and monetary system.

Furthermore, a complementary currency backed by a central bank digital currency can not only compensate for the demise of commercial bank money, but it can also democratise money creation. The authors also show that complementary currencies can have higher multiplier effects on local expenditure, allow central banks to control circulation velocity, and help countries in currency crises.

China has banned

private cryptocurrencies (Olcott 2021) and launched its own central bank

digital currency (CBDC). We now have a race between countries to issue

their own CBDC.

In the UK, the House

of Lords committee has concluded there is no convincing case for the

creation of a CBDC (Mozée 2022) and that it could cause bank runs.

According to the Centre for Macroeconomics, however, 84% of the European

economists surveyed favour a CBDC (Crumpton and Ilzetki 2021), and so

do we. We are economists specialising in the management and study of

electronic community or ‘complementary’ currencies on a regional scale

in Spain, Switzerland, and Germany. Our experience shows that CBDCs,

properly designed, can help stabilise our financial and monetary system.

But first, what is

likely from the introduction of CBDCs? It could just mean that central

bank accounts would be available to everyone, not just to banks. Most

people would probably opt to move their money from their checking

account to a central bank deposit, since the latter is safer. This could

cause bank runs, which worries the House of Lords. But runs can be

avoided if there is a gradual transition to the amount of CBDC each

citizen is permitted. Establishing such limits is only possible if the

CBDC is not a private cryptocurrency but rather a central bank deposit.

Making central bank

deposits available to all citizens is a simple change that can

eventually transform the monetary system as we know it. Given that banks

create new money (deposits) out of thin air whenever they make loans,

any public preference for central bank deposits over commercial banks

could make this old money creation mechanism non-viable. Banks would

have to generate new credit products, transforming themselves into more

‘normal’ businesses in the process.

If most people hold

CBDCs instead of checking accounts, banks would no longer be ‘too big to

fail’. In the event of bankruptcy, the system of electronic payments

would continue, hosted by the central bank, eliminating the need for a

public bailout. This point is stressed by Miguel Angel Fernández

Ordóñez, the Bank of Spain’s former governor, in his book, Adiós a los bancos.

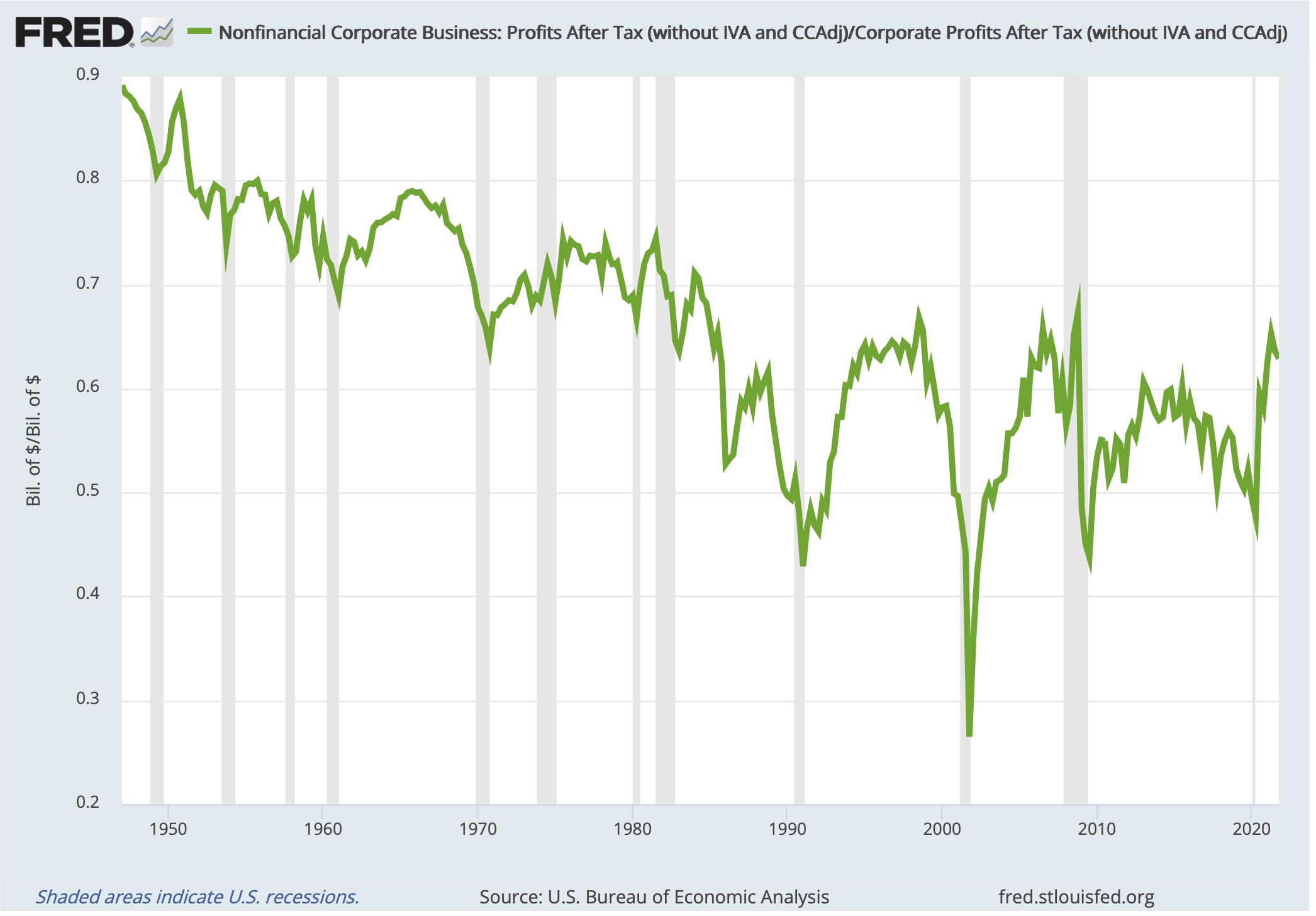

Because they are insured against their outsized risks, banks regularly

earn outsized profits. With a CBDC, the long-term trend of nonfinancial

corporations earning an ever-smaller share of corporate profits would be

curbed, resulting in a more balanced distribution of income, as seen in

the following US series (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Nonfinancial corporate business: Profits after tax

Source: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=Nprc

The implementation

of CBDC and less money creation by banks would mean greater systemic

stability for another reason: bank money is highly ‘pro-cyclical’.

Central banks could issue CBDCs counter-cyclically, moderating economic

cycles rather than magnifying them. As Yale economist Irving Fisher

wrote in 1935, ending private banks’ ability to create money would both

nationalise money and fully privatise banking. More recently, former

Bank of England Governor Mervyn King (2010) argued that “[o]f all the

many ways of organising banking, the worst is the one we have today”.

Nonetheless, many

fear that a CBDC will give the government a window on every transaction,

ending the anonymity of cash. But with almost three-quarters of the

value of US consumer purchases now electronic (Federal Reserve Bank of

San Francisco 2019), this window is already open to a valid search

warrant. Legitimate purchases with a CBDC can be similarly shielded. On

the other hand, there is a real security gain in combating laundered

money. Current efforts to track the assets of Russian oligarchs have

brought this to the fore. Novokmet (2018) and his colleagues conclude

that Russian secretion of private wealth abroad is unparalleled in

modern history and now totals as much as 100% of their country’s annual

GDP.

There is much more

hidden wealth to be taxed. The 2020 UN High-Level Panel on International

Financial Accountability, Transparency and Integrity (FACTI) estimates

show a 2019 tax loss of about $600 billion. Using World Bank figures on

global tax/GDP ratios and global GDP,1 one can estimate this loss at 4.61% of global tax revenues. This global tax to GDP ratio is an average,

so the progressivity of statutory tax rates, both within and between

countries, means this estimate of tax loss is highly conservative. ...

more at VOX

© VoxEU.org

Key

Hover over the blue highlighted

text to view the acronym meaning

Hover

over these icons for more information

Comments:

No Comments for this Article