As an international currency, the euro has always been a distant second to the dollar. The idea of a greater international role for the euro has been floated, but without major institutional reform, the euro will not become a dominant currency.

When created two decades ago, the euro

immediately became the world’s second most important currency. But it

has remained a distant second to the US dollar. Its internationalisation

peaked in 2005 and went into reverse with the euro crisis, never fully

recovering since. Although some predict the demise of the dollar, its global hegemony persists.

The European Union is now

considering promoting a greater international role for the euro, in

particular in the context of an ambition for the EU to play a more

strategic geopolitical role

Faced with a United States administration

less inclined towards multilateral solutions and willing to use its

currency to extend its domestic policies beyond its borders (for

instance by forcing European firms to cut ties with Crimea, Cuba or

Iran), the European Union is considering promoting

a greater international role for the euro. Regular attention is now

paid to it in policy speeches, in particular in the context of the

European Commission’s stated desire for the EU to play a more strategic

geopolitical role. The European Central Bank, meanwhile, has abandoned

its traditional neutral stance on this question.

Pros and cons of a dominant currency

Despite being an international currency,

the euro is not a dominant one. Does this matter and would it be

beneficial for the EU if the euro had a greater international role? As a

dominant currency, the dollar enjoys certain advantages: seigniorage

revenues from the significant holdings of cash abroad (as long as rates

are positive); lower yields for the government from a safety and

liquidity premium; an aggregate return on foreign assets superior to the

cost of foreign liabilities; lower transaction costs for its citizens

and companies; a competitive advantage for domestic banks which issue

international currency; a lower dependence on the US driven global

financial cycle; and an additional geopolitical instrument to ensure

financial and economic autonomy.

However, a dominant currency also entails

costs. In times of global uncertainty, the dominant currency needs to

provide some form of insurance to the rest of the world in two ways.

First, the appreciation of the dominant currency, caused by an increase

in demand for a ‘safe’ currency during times of uncertainty, can lead to

negative wealth effects for the country if its debt is denominated in

the dominant currency but its assets are invested abroad in local

currencies. Second, to avoid the collapse of the global financial

system, the central bank issuing the dominant currency needs to play the

role of international ‘lender of last resort’ (e.g. via currency swap

lines with other central banks), which could interfere with its domestic

policy objectives. Finally, to achieve the status of globally dominant

currency, a global safe asset needs to be provided, which results in

periods of significant capital inflows that combine with current account

deficits.

The euro area does not provide a large and elastic supply of a safe asset

These cons explain why some countries,

such as Germany, were reluctant to promote the internationalisation of

their currencies in the past. They feared it could weaken control over

monetary policy, generate undesirable exchange rate volatility and

result in excessive appreciation of the currency, thus undermining their

export-dependent growth model. The euro area and the ECB inherited this

pre-euro German position and left the role of the euro to be determined

by market forces and other central banks. This is now changing in

official communications, but are the steps taken sufficient?

Determinants of global currency status

Historically, countries issuing dominant

currencies have been characterised by a large and growing economy, free

movement of capital, an explicit willingness to play an international

role, stability (monetary, financial, fiscal, institutional, political

and judicial), an ability to provide a large and elastic supply of safe

assets, developed financial markets, and significant geopolitical and/or

military power. How does the euro area measure up?

Thanks to a large economic base, the euro

area partially fulfils the first criterion. Though not the foremost

global economic power, the monetary union represents one of the largest

economic blocs in the world even if it lacks economic dynamism. It also

fulfils the second criterion, as free movement of capital is solidly

entrenched in European Treaties. The willingness to play an

international role was previously not there, but this has changed.

The stability criterion is only partly met

in the euro area. Despite missing its inflation target in recent years,

the ECB has ensured a stable value of the currency in the last two

decades. Financial stability risks, after being at the root of the euro

crisis, have been reduced. And most euro-area countries fare pretty well

in terms of judicial and political stability, despite some setbacks in

some countries in recent years.

Nevertheless, flaws in the architecture of

the monetary union have sometimes led investors to doubt its long-term

durability, or the irreversible participation of some countries. These

doubts came to the fore during the euro crisis and redenomination risks

have periodically resurfaced since then, notably in Greece in 2015 and

in Italy in 2018. Finally, fiscal stability is a more complex issue in

the euro area than in other jurisdictions due to decentralised fiscal

and centralised monetary policy. The European Stability Mechanism (ESM)

and the ECB’s Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) programme have

addressed this issue to some extent.

However, the euro area does not provide a

large and elastic supply of a safe asset. Safe assets are liquid assets

that credibly store value at all times, in particular during systemic

crises, and there is a high demand for them. Sovereign debt securities

from advanced countries play this role, as long as public finances are

considered sound by the markets.

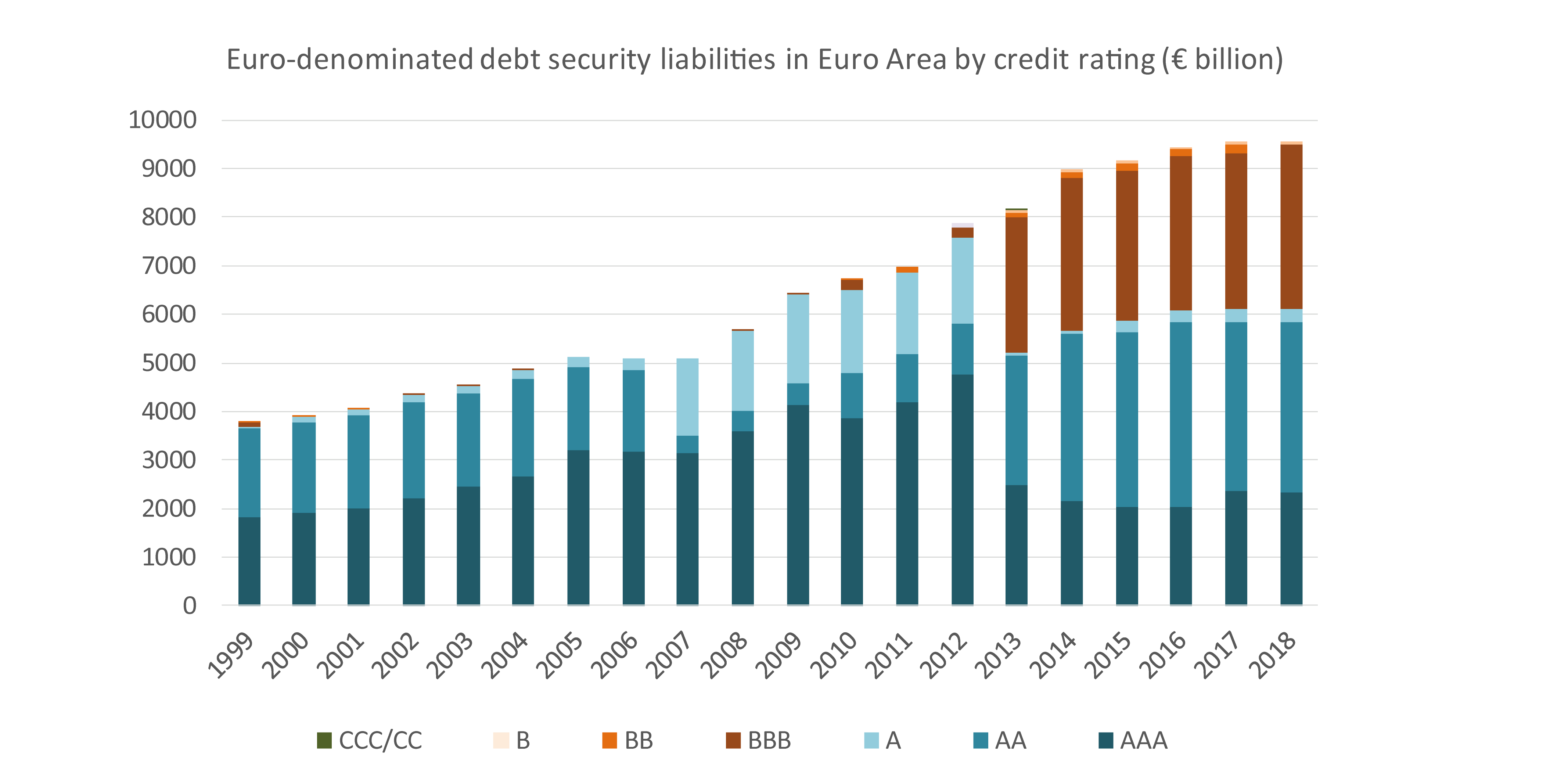

From the creation of the euro to the euro

crisis, sovereign bonds from euro-area countries enjoyed this status –

but several lost it during the euro crisis. The stock of AAA-rated debt

securities from the euro area declined from around 40% of its GDP in

2008 to 20% in 2018 (Figure 1), while the supply of AAA-rated US Federal

debt securities increased from 65% of GDP to more than 100%.

Figure 1: Supply of safe assets from the euro-area (€ billions)

Source: Bruegel based on Bloomberg for

bonds issued by EFSF, EU, ESM and EIB, S&P for credit ratings and

Eurostat for government debt securities. Note: includes bonds issued by

the 19 euro-area countries, the European Financial Stability Facility,

the European Union, the European Stability Mechanism and the European

Investment Bank.

As far as the development of financial

markets is concerned, the euro area’s capital markets are much less

developed, less liquid and less deep than in the US. They are still

heavily fragmented along national lines, despite the Capital Markets

Union initiative. Finally, even though Ursula von der Leyen’s European

Commission considers itself a “geopolitical Commission”, the EU is far from being a dominant military power.

No shortcut to dominant status

Overall, the monetary

union does not meet all the criteria for the euro to become a dominant

currency. The only solution is to improve the institutional setup of the

monetary union. Besides completion of the banking union and the

deepening of capital markets, the supply of safe assets is essential. It

is also crucial to boost growth in order to make the euro area an

attractive destination for investment, but also to improve the prospects

of individual countries so that their debt is considered safe. Finally,

a more determined attitude on the part of the ECB (by offering more

easily currency swaps to countries in which euro liquidity is important)

would help, as would progress on an EU external/defence policy and a

more visible geopolitical role.

Overall, the monetary union does not meet all the criteria for the euro to become a dominant currency

Current minor initiatives put forward by

the European Commission – promoting the labelling of energy contracts

and derivative clearings in euro, or encouraging the systematic use of

the euro by institutions such as the European Investment Bank (EIB) and

the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, or by third

countries through diplomacy – are useful, but insufficient.

Two issues should now be prioritised.

The increase in the supply of safe assets during the COVID-19 crisis

Significant steps have been taken to

ensure that the supply of euro-denominated safe assets is increased.

First, the ECB’s Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme has ensured the

stability of the monetary union by allowing governments to issue debt

easily, thereby also increasing the supply of safe assets. Second, the

Eurogroup agreed

on 9 April 2020 to increase joint borrowing by up to €540 billion: €200

billion through the EIB, €100 billion through the new EU ‘SURE’ credit

line to help countries finance temporary lay-off benefits and up to €240

billion through the ESM. Third, the European Council reached

an agreement on 21 July 2020 to issue up to €750 billion-worth of EU

debt to finance its recovery plan, using the EU budget as a mechanism

for borrowing.

As the fall in sovereign spreads shows,

markets have interpreted these decisions as a commitment by EU countries

to stick together, and as an improvement in the institutional set-up of

the Economic and Monetary Union. This should increase its stability and

reinforce the international role of the euro. The euro indeed

appreciated when the €750 billion package was agreed, and when France

and Germany made the initial proposal in May (Figure 2).

Figure 2: US dollar – euro exchange rate

Source: Bruegel based on Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

It is now of central importance that the agreed package clears its final legislative hurdles. Strong governance mechanisms will also bolster the credibility of the package. An important discussion is about the issuance of green bonds (as well as social bonds),

and whether they represent an opportunity to create a new market with

Europe in the lead, or rather a disruption that would fragment the

market for EU bonds. Finally, the EU should reconsider whether it is

sensible to pay back the debt as originally planned or if it is

preferable to roll it over when it matures. Repaying the debt would not

only be a major economic burden without benefit but would also

counteract the strategy to boost the international role of the euro.

Promoting the euro by boosting growth

An ambitious and strategic growth agenda

for the next decade is also needed. Policymakers must ensure that funds

from the recovery plan are used wisely to reboot the European economy

once the coronavirus is defeated. This will provide a double dividend

for the euro as an international currency by increasing the euro-area’s

attractiveness and by boosting ratings of weaker countries, thus

increasing the overall supply of safe assets.

The EU recovery fund will be particularly

crucial in that regard. It should complement national stimulus measures

to prevent a slow recovery, but given the usual sluggishness

in the disbursement of EU funds, its macro effect will only start to

materialise in a couple of years. That’s why the recovery fund should

mainly aim at establishing a new growth model in Europe and focusing on

the necessary reforms.

Overall, the euro is not yet set to

dominate as a global currency as long as no major further

institutional steps are taken. There is no shortcut to becoming a

dominant currency.

© Bruegel

Comments:

No Comments for this Article