In the face of the COVID-19 crisis, massive purchases of

government bonds by the ECB through its Pandemic Emergency Purchase

Programme, or PEPP, were crucial for averting a financial crisis.

However, as a side effect, the PEPP diminishes even further the supply

of euro denominated safe assets available to other central banks.

This creates a conundrum for the ECB. If it continues buying

government bonds to support the euro area economy, it limits the

availability of assets for use as foreign exchange reserves by central

banks still further. Based on Eichengreen and Gros (2020), we propose a

way out: the issuance of ECB Certificates of Deposit (ECBCDs).1

Strengthening the international role of the euro

Strengthening the international role of the euro is official policy

of EU institutions. According to its 2020 work programme, the European

Commission intends to adopt a strategy of “Strengthening Europe’s

Economic and Financial Sovereignty”. The ECB has similarly embraced

this aim (Panetta 2020).

One measure often used to gauge the international role of the euro is

its share in foreign exchange reserves. This share is in the range of

20% to 25%, or about one third of that of the US dollar. It is often

argued that the euro’s share is so low because there do not exist enough

euro-denominated safe assets (e.g. Valla 2019, Habib et al.

2020). Reserve managers, the argument goes, prefer to invest in

low-risk, liquid government bonds. In practice, an AAA/AA rating is

needed to qualify for safe asset status. Only four euro area countries

have this rating (FR, DE, NL and AT), and their combined marketable debt

of €5 trillion is dwarfed by the close to $20 trillion of US Treasury

bonds outstanding.

Moreover, until now, there has not existed a significant supply of

safe common euro area assets. The fiscal measures adopted by the EU and

its member countries hold out promise that this supply might now

increase. However, any such tendency is being offset by the ongoing

asset purchases of the Eurosystem.

ECB bond buying and the supply of safe euro assets

Between 2014 and 2018, the ECB purchased roughly €2.2 trillion of

government bonds under the PSPP. Roughly 60% of this was spent on the

bonds of the four countries supplying safe assets. Since these bonds are

now held by the Eurosystem and are no longer on the market, this has

effectively reduced the scope for international investors to hold euro

assets.

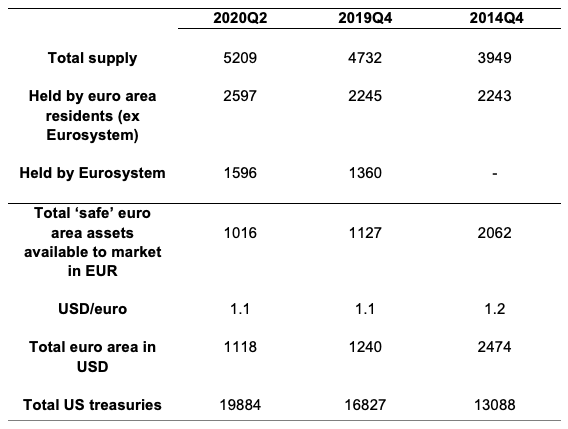

Table 1 shows the impact of the PSPP up to now: a drop in the

marketable amount of about €1.4 trillion between 2014 and 2019. (The

total includes supranational bonds of €200 billion.)

In addition, European banks are required to hold ‘high-quality liquid

assets’ in proportion to their balance sheets, for which public sector

bonds are their main source. Hence another significant fraction of euro

area public debt securities is absorbed by the banks (about €1.5

trillion by end 2019). Together with other euro area sectors

(insurance, etc.) amounts available for international investors, such as

reserve managers, were limited to €1.1 trillion at end-2019 (fourth row

of Table 1).

The PEPP initiated in March 2020 constitutes an extension of the

PSPP. So far this year, the supply of safe government bonds available

to global reserve managers has actually declined (from €1.1 to €1.0

trillion) because the Eurosytem and other euro area residents have been

buying safe assets more quickly than governments have issued them.

Looking forward, the €1.35 trillion of additional purchases planned

by the ECB (equivalent to 12% of euro area GDP) over the next 18 months

are larger than the expected deficits of euro area member states over

the same period.

The continuing operation of the PEPP will also reduce the supply of

common safe assets expected from the Next Generation EU financial

package of support to member states. The Eurosystem is likely to

purchase as much as half of the (maximum of) €850 billion of common

bonds that the EU is planning to issue.2 The additional net

supply of euro safe assets may thus increase only by about €425 billion

(equivalent to 4% of global reserve holdings).3

Table 1 Stock of debt securities outstanding available for the rest of the world (not held by euro area residents)

Note: As supplier of safe euro assets to the market,

we considered the AAA euro area countries (Germany, France, the

Netherlands, and Austria) and the supranationals. To obtain the amounts

displayed in the table we proceeded on three steps. First, from the

Government Finance Statistics (GFS) we retrieved the total amount of

debt securities outstanding for the suppliers of safe assets considered,

for June 2020, December 2019, and December 2014. Second, from the

Securities Holding Statistics (SHS) we retrieved data on the total

amount of debt securities issued by the governments of the safe assets

suppliers mentioned above and held by euro area residents for 2020Q2,

2019Q4, and 2014Q4. These data series do not include the debt securities

held by the Eurosystem, so we considered the PSPP and the PEPP

breakdown history database, to obtain cumulative data until June 2020

and December 2019 on the securities issued by the safe assets suppliers

under analysis and held by Eurosystem under PSPP. Finally, we subtracted

from the total outstanding amount of debt securities, both the amount

held by the Eurosystem under PSPP and PEPP (if applicable) and the

amount held by euro area residents. The numbers on the first four rows

are expressed in billion EUR, the numbers on the last two rows are in

billion USD.

Source: Own calculations based on ECB

Statistical Data Warehouse (Securities Holding Statistics, PSPP

breakdown history and Government Finance Statistics) and TreasuryDirect.

How to increase safe assets

The ECB (or rather the Eurosystem) finances its bond purchases by

issuing bank deposits. These deposits are not tradable outside the

banking system (central banks can’t hold them as foreign

reserves). Thus, the PEPP reduces the supply of euro safe assets to the

market and enlarges bank balance sheets, on both counts making it more

difficult for central banks around the world to invest their reserves in

euros.

We propose a simple solution to this conundrum: the ECB should make

its liabilities tradable. The easiest way would be for the ECB to issue

tradable Certificates of Deposit (ECBCDs). ECBCDs would constitute a

euro area safe asset par excellence. They would be an attractive way for

foreign central banks to hold reserves in euros, provided of course

that the certificates in question can be traded globally and are issued

in a sufficiently large amount to create a liquid market.

One would not need to invent a new legal basis for this instrument.4

Item 4 of the balance sheet of the Eurosystem is 'debt certificates

issued'. The ECB’s own definition for this item is as follows:

“ECB debt certificates’ means a monetary policy instrument used

in conducting open market operations, whereby the ECB issues debt

certificates which represent a debt obligation of the ECB in relation to

the certificate holder”.

ECBCDs would be attractive because they would not be bottled up in

the euro area banking system. Normally only banks (officially monetary

financial institutions, or MFIs) are entitled to hold accounts with the

ECB or the National Central Banks of the Eurosystem. The legal

provision governing the assets in these accounts is clear:

“The ECB shall not impose any restrictions on the transferability of ECB debt certificates”.

This implies that there would be no legal obstacle for a foreign central bank to acquire ECBCDs.5

Neither would market size be a problem. At present,6

liabilities to banks are some €3 trillion euro for the Eurosystem as a

whole. This suggests that the ECB could easily issue €1 trillion in

ECBCDs without having to worry that this amount would have to be reduced

in the foreseeable future.

The present legal basis for ECBCDs limits their maturity to 12

months, which might limit their attraction. IMF data show that central

banks hold about $1.5 trillion of reserves in the form of deposits, with

about two thirds held at other central banks and one third held at

commercial banks. ECBCDs should constitute an attractive substitute for

deposits held at euro area national central banks (or even deposits at

the Bank for International Settlements). This should ensure a small but

significant market for short-term ECBCDs.

However, the market for medium maturities is evidently much larger.

McCauley (2020) shows that Treasury bills (with a maturity of less than

one year) account for only about 1/10th of total Treasury holdings (with

bonds constituting the remainder). The Swiss National Bank reports that

the average maturity of its fixed-income investments is over

four years. All this indicates that it would be important to offer

foreign central banks an instrument with a maturity of several years.

One concern with the ECB in issuing longer-dated CDs is that such

issuances would make it difficult to reverse the asset purchases or to

reduce lending to banks. However, the balance sheet of the Eurosystem is

unlikely to shrink even if the current crisis is overcome. The ECB is

granting loans of three years to banks under the targeted longer-term

refinancing option (TLTRO). There is thus little danger that the amount

of ECBCDs outstanding could be larger than lending to banks and the

amount of assets held, suggesting that it should be possible to issue

three-year ECBCDs.

One objection to this proposal is that issuing these certificates

could be seen as draining liquidity from banks, which could be

interpreted as a tightening policy. But the counterpart of the issuance

of tradable ECBCDs would be lower deposits at the ECB which carry a

negative rate and thus diminish bank profits. Although this problem has

been partially addressed by the tiering of the deposit rate, it could

be reduced further, thus alleviating the tax on bank profits implicit in

negative deposit rates and make the monetary stance more effective. One

could therefore argue that the issuance of ECBCDs is entirely

compatible with the ECB’s primary mandate of maintaining price stability

(as well as its subsidiary mandate of supporting the general policy of

the EU).

Conclusions

Large-scale bond buying under the PEPP reduces the supply of safe

euro assets to the market. This effect could be neutralised, at least

in part, were the ECB were to issue its own Certificates of Deposit.

The legal framework for issuing Certificates of Deposit already

exists. The ECB could immediately issue between €2 trillion and €3

trillion of ECBCDs, thereby significantly increasing the supply of euro

safe assets to the market and helping to internationalise the euro.

Authors’ note: Angela Capolongo is now working at the European

Stability Mechanism (ESM). This column was completed before she joined

the ESM. The views expressed here are solely those of the authors and

are not to be reported as those of the ESM.

References

Eichengreen, B (2011), Exorbitant Privilege: The Rise and Fall of the Dollar and the Future of the International Monetary System, Oxford University Press.

Eichengreen, B and M Flandreau (1996), “Blocs, Zones and Bands:

International Monetary History in Light of Recent Theoretical

Developments”, Scottish Journal of Economics 43(4): 398-418.

Eichengreen, B (2016), “The future of the international monetary and financial architecture”, Conference proceedings.

Eichengreen, B, A Mehl and L Chitu (2018), How Global Currencies Work, Princeton University Press.

Eichengreen, B (2020), “Dollar Sensationalism”, Project-syndicate.org, 12 August.

Eichengreen, B and D Gros (2020), “Post-COVID-19 Global Currency

Order: Risks and Opportunities for the Euro”, Study for the Committee on

Economic and Monetary Affairs, Policy Department for Economic,

Scientific and Quality of Life Policies, European Parliament, September.

Hardy, D C (2020), “ECB Debt Certificates: the European counterpart

to US T-bills”, Department of Economics Discussion Paper No. 193,

University of Oxford.

McCauley, R N (2020), Safe Assets and Reserve Management, Chapter 8 in J Bjorheim (ed.), Asset Management at Central Banks and Monetary Authorities, Springer International Publishing.

Panetta, F (2020), “Unleashing the euro’s untapped potential at global level”, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, Meeting with Members of the European Parliament, 7 July.

Habib, M M, L Stracca and F Venditti (2020), “The Fundamentals of Safe Assets”, ECB Working Paper no.2355, January.

Valla, N (2019), “Safe Assets in a Monetary Union”, Presentation to

the CEPR Research and Policy Network on European Economic Architecture,

16 April.

Endnotes

1 Previously, Hardy (2020) also proposed the introduction of the ECB

certificates, that could serve as counterpart to the short-term US

assets, such as T-bills.

2 The

(self-imposed) limit of Eurosystem holdings of national government

bonds is one third. For so-called ‘supra-national’ debt it is

half. Close to one half of ESM bonds are held by the Eurosystem (though

not by the ECB as a legal entity). Supra-national bonds are important

for national central banks that could not otherwise buy their share of

national debt because they would exceed the one-third limit.

3 Another unknown is the size of bank balance sheets and their demand

for sovereign debt. If households continue to accumulate bank deposits

but the demand for credit remains weak, banks will have little choice

but to accumulate even more government securities (which have a zero

risk weight). Over

the first six months of 2020, commercial banks increased their holdings

of Euro Area government debt securities by more than €300 billion, an

amount similar to purchases by the Eurosystem (somewhat more than 400 billion).

4 The legal base for this instrument was created in 2015 and can be found here (2.4.2015 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 91/21 ).

5 Certificates of Deposit are not unusual instruments for a central

bank to issue. A case in point is Denmark, where the interest rate on

certificates of deposit is the central bank’s main policy instrument. In

the Danish case this instrument is very short term: loans to banks and

CDs have the same maturity, namely one week (https://www.nationalbanken.dk/en/monetarypolicy/instruments/Pages/Default.aspx). The Swedish national bank also uses certificates of deposit as its main policy instrument.

6 August 2020 (https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/wfs/2020/html/ecb.fst200804.en.html)