It considers a mechanism involving large transfers of euro area sovereigns from the ECB to the ESM as a possible way forward

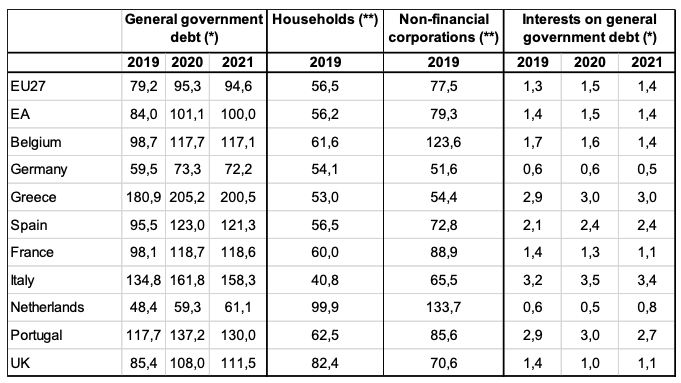

Following the health crisis, fiscal deficits and sovereign

debts in the euro area are projected to deteriorate dramatically (Table

1). The increase in the average debt ratio in the euro area is estimated

to be over 15%, bringing it over 100%. It will climb by about 20% in

France and about 30% in Italy and Spain. Some countries, notably Belgium

and France, also display a large increase in private sector

indebtedness. The rise in private debt is relevant as it may foreshadow a

future increase in sovereign debt, to the extent that the public sector

is forced to take it upon itself to contain damage to the economy from

insolvencies.

Table 1 Government, non-financial private sector debts and interests on general government (% of GDP)

In this column, I argue that sovereign debt externalities remain

important in the euro area, even in the new environment of permanently

lower interest rates and, moreover, that these externalities justify

common euro area policies to deal with excessive sovereign debt

accumulation and attendant risks to the euro area’s financial stability

(Micossi 2020).

Sovereign debt restructuring not a solution

Before turning to feasible policies and policy trade-offs, I need

first to discuss what is not a feasible solution, and that is preventive

debt restructuring country by country. This approach is predicated on

the importance of moral hazard considerations in driving sovereign debts

(as in Benassy-Quéré et al. 2018) but is highly questionable both

analytically and empirically. Indeed, there is scant evidence that

countries’ debt policies are motivated by moral hazard (Tabellini

2017).

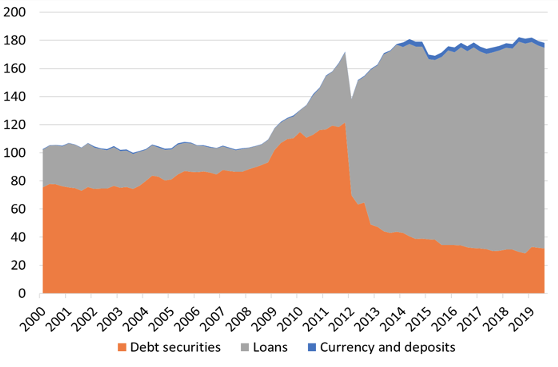

In all cases, within the euro area the experience with debt

restructuring in reducing the debt burden and restoring debt

sustainability was far from encouraging. Figure 1 shows that massive

private debt restructuring in Greece in March 2012 led to an increase in

overall government exposure, owing to the need to fill the gap opened

by vanishing private finance. As Greece had already lost market access,

an increasing role in providing liquidity to the Greek financial system

was then taken up by the ECB, through its emergency liquidity assistance

– which thus evolved from an emergency credit line for individual banks

in difficulty to an emergency macro-financing channel (Micossi 2015).1

Figure 1 Greek government debt (% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat.

Confirmation in the summer of 2011 that Greek private debt would

indeed be restructured triggered the start of contagion to Spain, Italy

and even France. Eventually, it took the ECB’s new OMT programme, which

was launched in September 2012 and promised unlimited purchases of

sovereigns under speculative attack, to halt the run of investors on

indebted countries.

This discussion points to an inevitable conclusion. While debt

restructuring cannot be ruled out eventually as a component of actions

to restore the market access of a country unable to service its public

debt, the notion of preventive debt restructuring when granting ESM

financial assistance should simply be removed from the table as utterly

destabilising.

Macro policy externalities in the euro area

Against this background, the question arises as to whether high

sovereign debt can be left to euro area member states to manage by

themselves, with a repetition of the policies that followed the

financial crisis at the beginning of the decade, or whether instead a

different approach is justified.

In his influential presidential address to the American Economic

Association, Blanchard (2019) argued that in the new environment of low

interest rates expected to last for an indefinite future, policy

trade-offs between debt stabilisation and output stabilisation with

fiscal policy have shifted fundamentally in favour of the latter goal.

Based on this analysis, Blanchard et al. (2020) have proposed

substantial modifications of euro area fiscal rules that confine debt

stabilisation to the backstage.

However, their results may have been overstated owing to their

insufficient consideration of debt policy externalities within the euro

area. An important feature that must be considered in this context was

described in De Grauwe’s (2011) seminal paper – it is the fact that the

common currency is not available to individual euro area member states

to stabilise their sovereign debt market without the consensus of (a

majority of) the governing board of the ECB. Fear that such support may

be withdrawn may generate a financial shock shifting the economy of a

member state to a ‘bad equilibrium’ involving an investor run on his

sovereigns and, as a consequence, fresh threats to the survival of the

euro spreading contagion to other euro area members.2

The problem is kept ‘under the carpet’ at present by the ECB policy

of flooding the system with liquidity to counter the economic impact of

the pandemic, but it is bound to resurface at some stage once economic

output returns to pre-crisis levels, also in view of the large increase

in sovereign debts under way. It is aggravated by the incomplete

architecture of the monetary union, which still lacks cross-border

deposit insurance, a credible crisis resolution mechanism for banks, and

a full public backstop for both in case of a systemic bank crisis,

while banks continue to hold substantial amounts of national sovereigns.

Consequently, the ‘doom loop’ between bank crisis and sovereign crisis

may still reappear following, for example, a rating downgrade of a

highly indebted sovereign below investment grade.

Common policies to mitigate sovereign debt risks in the euro area

The analysis above has left us with some important conclusions that

point to the need to adapt common policies in order to reduce high-debt

risks. A way forward would be offered by engineering large transfers of

euro area sovereigns from the ECB to the ESM, de facto keeping a

substantial part of the debt out of the market for an indefinite future.

The euro area would utilise the credit standing of its institutions to

lower sustainability risks and debt service.

More specifically, the ESM would purchase the sovereigns held by the

European System of Central Banks (ESCB) as a result of its asset

purchase programmes (APP and PEPP). The default risk of sovereigns

purchased from the ESCB would continue to remain with national central

banks, as it is today, and would not be transferred to the ESM. At

maturity, the sovereigns held by the ESM would be renewed into new

securities with very long maturity, de facto turning them into

‘irredeemables’.

The purchases would be funded by the ESM by selling its own

securities in financial markets. Like all outstanding ESM liabilities,

these securities would be guaranteed by its sizeable (callable) capital.

In addition, they would enjoy the guarantee of its member states

already in place for ESM liabilities. This double guarantee, together

with the de facto guarantee maintained by national central banks on

their sovereign paper, should be more than enough to ensure the AAA

rating for ESM securities without any special seniority privilege – a

major drawback of the various proposals for a safe asset that were

formulated in the past would thus be eliminated.3

This scheme has some other attractive properties that are worth

recalling. First, it would over time create suitable conditions for

unwinding the large increase in the ESCB balance sheets after

quantitative easing policies come to an end. Second, by bringing to the

market a large supply of new high-quality assets, the scheme is likely

to relieve the downward pressure on interest rates in the bond markets

of ‘safe’ (low debt) euro area countries, opening the way to interest

rate increases there even with present ECB policies.

References

Alcidi, C, A Capolongo, and D Gros (2020), “Sovereign debt

sustainability in Greece during the economic adjustment programmes:

2010-2018”, study prepared by CEPS in collaboration with NIESR and

ECORYS for the European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and

Financial Affairs, forthcoming.

Bénassy-Quéré, A, M Brunnermeier, H Enderlein, E Farhi, M Fratzscher,

C Fuest, P O Gourinchas, P Martin, J Pisani-Ferry, H Rey, I Schnabel, N

Véron, B Weder di Mauro, and J Zettelmeyer (2018), “Reconciling risk sharing with market discipline: A constructive approach to euro area reform”, CEPR Policy Insight No. 91.

Blanchard, O (2019), "Public Debt and Low Interest Rates", American Economic Review 109(4): 1197-1229.

Blanchard, O, Á Leandro, and J Zettelmeyer (2020), “Revisiting the EU

fiscal framework in an era of low interest rates”, mimeo, 9 March.

Brunnermeier, M, S Langfield, M Pagano, R Reis, S Van Nieuwerburgh, and D Vayanos (2017), “ESBies: safety in the tranches”, Economic Policy 32(90): 175-219.

Corsetti, G, L P Feld, P R Lane, L Reichlin, H Rey, D Vayanos, and B Weder di Mauro (2015), A New Start for the Eurozone: Dealing with Debt, Monitoring the Eurozone Report, CEPR.

De Grauwe, P (2011), “The Governance of a Fragile eurozone”, CEPS Working Document No. 346.

ESRB (2018), “Sovereign bond-backed securities: a feasibility study -

Volume I: main findings”, European Systemic Risk Board, Frankfurt

/Main, January.

Leandro, Á, and J Zettelmeyer (2019), “Creating a Euro Area Safe

Asset without Mutualizing Risk (Much)”, PIIE Working Paper 19-14,

August.

Micossi, S (2015), “The Monetary Policy of the European Central Bank (2002-2015)”, CEPS Special Report No. 109.

Micossi, S (2020), “Sovereign debt management in the euro area as a

common action problem”, CEPS Policy Insight No. 2020-27, October.

PIIE (2020), The Greek Debt Crisis No Easy Way Out, Case Study.

Tabellini, G (2017), “Reforming the Eurozone: Structuring versus restructuring sovereign debts”, VoxEU.org 23 November.

Endnotes

1 Zettelmeyer has argued that the bad outcome of the 2012 Greek debt

restructuring is due to the delay in decisions (PIIE 2020), but his

interpretation is difficult to reconcile with the events that have been

described (cf. Corsetti et al. 2015). In a forthcoming paper prepared

for the European Commission, Alcidi et al. (2020) underline the adverse

effects of restructuring on growth, in turn entailing that, in order to

achieve a large and sustained reduction in the debt-to-GDP ratio, the

haircut on nominal debt must be “very, very large”, thus possibly

unrealistic to be accepted and to happen in an orderly way.

2 For the modifications of Blanchard’ model required to take account of this dimension of the problem, see Micossi (2020).

3 Brunnermeier et al. (2017) made an influential proposal for

developing sovereign bond-backed securities (SBBS) with varying

seniority tranches, with the most senior tranche (European Safe Bonds,

or ESBies) being as safe as the German bund. Being based on private

contracts, their SBBS would not entail any risk sharing. A High-Level

Task Force on Safe Assets, established by the ESRB, was set up to assess

the feasibility and impact on financial stability of creating a market

for SBBS. They concluded (ESRB 2018) that the development of a

demand-led market for SBBS might be feasible ‘under certain conditions’,

but could not agree either on its desirability (for the feared impact

on sovereign debt markets) or its viability without regulatory support

(including the introduction of concentration charges to penalise banks’

holdings of national sovereigns, the usability of ESBies as collateral

in ECB operations, and complex enabling product legislation). Further

possibilities for the creation of a European safe asset are discussed by

Leandro and Zettelmeyer (2019).