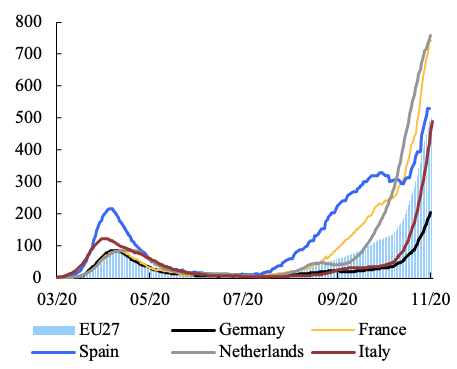

The European economy remains firmly in the grip of the

Covid-19 pandemic. Since September, the number of new infections has

been on the rise again in most European member states. By the time the

books were closed on our autumn forecast on 22 October, a second wave of

the pandemic was in full swing across much of Europe. With infections

spreading and hospitals under pressure once more, governments are left

with little choice but to put in place new restrictions to curb the

rapidly rising epidemiological trend and bring it back to more tolerable

levels. But the economy is still suffering from the deep contraction in

the first half of the year and authorities are striving to keep the

scope and duration of the restrictions to social life and economic

activity as limited as possible.

Figure 1 Covid-19 infections, 14-day incidence, selected member states

Notes: Reported new cases per 1000 persons

Source: European Centre for Disease Control, Eurostat

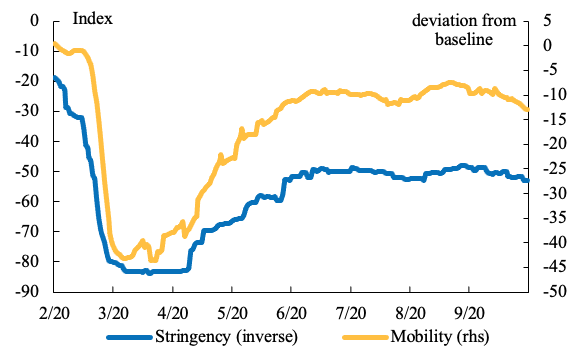

Figure 2 Stringency of restrictions and mobility, euro area composite

Note: Indicators weighted by the share of countries

in euro area GDP. Baseline = for each day of the week, the median

between 3 January and 6 February.

Source: Oxford Government Response dataset, Google.

Economic rebound interrupted as containment measures intensify

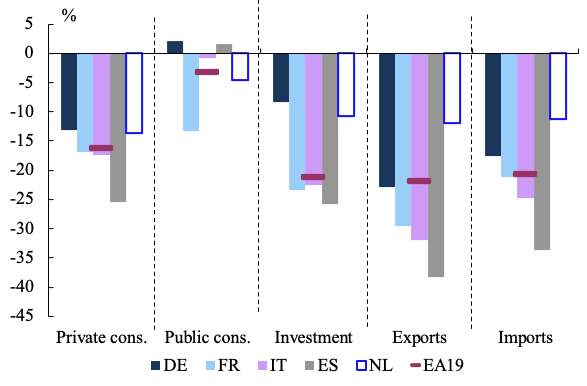

Nevertheless, we expect the measures to weigh substantially on

economic activity and sentiment this quarter and the next. Private

consumption and investment will again suffer, though to a lesser extent

than in the spring. As a result, the exceptionally strong rebound

observed in the third quarter is set to be interrupted abruptly in the

fourth quarter and growth momentum will be weak at the start of 2021

before a gradual resumption of the recovery can be expected.

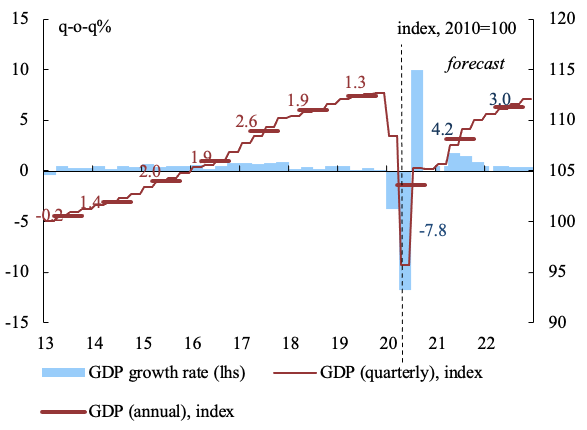

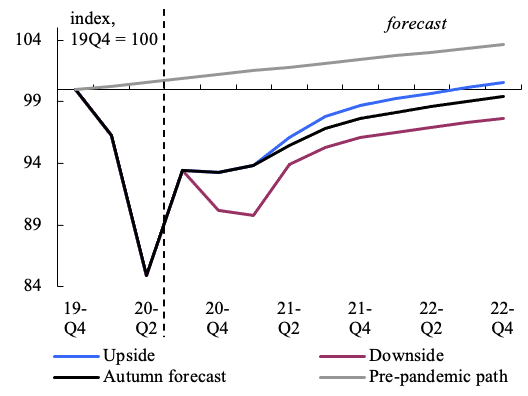

For 2020 as a whole, EU GDP is forecast to contract by about 7½%

before rebounding by 4% in 2021, which is some 2 percentage points less

than previously forecast, and by 3% in 2022. This implies that output in

the European economy would barely return to pre-pandemic levels in

2022. Moreover, the depth of the recession in 2020 and the speed of the

recovery in 2021 and 2022 are expected to vary widely across member

states. This reflects not only the severity of the pandemic and the

stringency of containment measures but also differences in economic

structures and domestic policy responses.

Figure 3 Real GDP, euro area

Source: DG ECFIN.

Figure 4 Expenditure breakdown, change between 2019-Q4 and 2020-Q2

Source: DG ECFIN.

Unprecedented drop in hours worked is set to delay rebound in employment

EU labour markets have come under severe strain. The decrease in

employment during the first half of the year was unprecedented. Thanks

to the prompt implementation in all member states of substantial support

measures, such as short-time work schemes, mass lay-offs have so far

been avoided, household incomes have been propped up, and unemployment

has increased only moderately. Looking ahead, the prospects for

employment are challenging. A significant amount of labour market slack

has accumulated since March, reflecting the sharp drop in hours worked

as well as workers leaving the labour force. As activity resumes, hours

worked are set to increase faster than headcount employment, limiting

the potential for net job creation, while the re-entry of workers into

the labour market could partly translate into an increase in

unemployment. Employment may also experience further losses when

short-time work schemes are discontinued. Despite the expected economic

rebound next year, employment is therefore expected to decline slightly

and the EU unemployment rate is set to rise further from 7.7% this year

to 8.6% next year, before declining to 8.0% in 2022. Labour markets are

expected to perform very differently across the member states over the

forecast horizon.

Figure 5 GDP, employed persons, and hours worked, euro area

Note: Pre-recession quarter = 100; only historical data.

Source: DG ECFIN

Resurgence of pandemic deepens uncertainty

The economic outlook is characterised by exceptionally high

uncertainty. For the baseline of our forecast, we assume that virus

containment measures are significantly tightened in the fourth quarter

of 2020 and that the stringency of these measures is subsequently eased

gradually in 2021. But a certain level of containment measures will

remain throughout the forecast horizon. The economic impact of a given

level of restrictions is assumed to diminish over time as the health

system and economic agents adapt to the COVID-19 environment. However,

as long as the pandemic hangs over the economy, the downside risks to

economic activity remain unusually large. In particular, the renewed

surge of the pandemic observed since October and the related containment

measures are already turning out to be stronger and more restrictive

than what we have assumed in our baseline.

The autumn forecast therefore features the simulation of a downside

scenario that assumes stricter and more protracted restrictions to

economic activity. Under such conditions, confidence would further

decline, holding back private consumption and investment more than

expected in our forecast. Financing conditions would also turn more

difficult as the liquidity and balance sheet positions of firms

deteriorate. Employment would weaken more too. In this downside

scenario, the euro area would fall into recession again with GDP levels

between 3 ½ and 4 percentage points lower in the fourth quarter of 2020

and the first quarter of 2021 than forecast in the baseline scenario.

The annual growth rates for 2020 and 2021 would be around -8 ½ % and 2 ¾

%, i.e. around ¾ percentage points and 1 ½ percentage points below the

baseline forecast. The level of economic activity would remain severely

depressed throughout the forecast horizon. And despite a gradual

recovery starting in the second quarter 2021, by the end of 2022, output

in the euro area would remain well below its pre-pandemic level.

Obviously, a more positive scenario cannot be excluded either. A

faster-than-expected decline in infection rates coupled with

faster-than-expected progress in the development of a vaccine and

advances in the medical treatment of the virus, would allow an earlier

easing of containment measures and lift confidence among households and

firms. Pent-up demand would boost consumption and bring forward private

investment. As a result, real GDP growth rates would be around half a

percentage point higher than expected in both 2021 and 2022, implying a

return to the pre-crisis output level over the course of 2022.

Figure 6 Real GDP, euro area, upside and downside scenarios

Note: The pre-pandemic path is based on growth rates

forecast in the winter 2020 interim forecast, and which were

extrapolated for 2022.

Source: DG ECFIN

Since our cut-off date, GDP flash estimates for Q3 have come out

higher than expected, demonstrating the responsiveness of the economy to

a relaxation of confinement measures. Ceteris paribus, the higher

turnout in the third quarter implies a higher growth momentum for the

expected recovery next year. A rapid implementation of the Recovery and

Resilience Facility of Next Generation EU and a last-minute trade deal

with the UK could also provide an additional lift to growth. By

contrast, the recent surge in infections and the resulting tightening of

virus containment rules since our cut-off date, point to further

downward risks to the economy in the short run.

Important patterns emerging from the forecast

In the face of so much uncertainty, forecasters must be modest about

the accuracy of their projections. Nevertheless, a few patterns are

emerging:

- First, the pandemic will continue to dominate the economic

trajectory. In the absence of an effective vaccine or medical treatment,

governments will continue to impose restrictions as needed to protect

their national health systems and this will continue to weigh on

economic prospects.

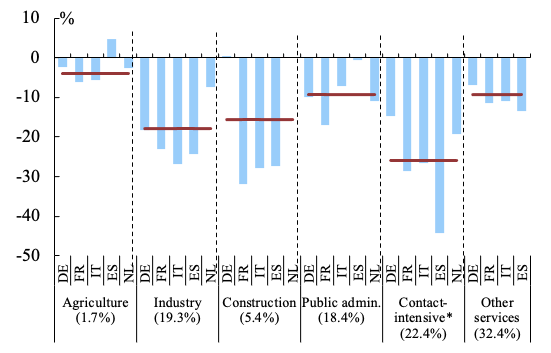

- Second, the economic consequences differ greatly between sectors,

socio economic groups, and member states. Unlike in past recessions, the

Covid-19 shock is hitting contact-intensive services in particular,

including tourism and leisure but also to some extent retail and

transport. Agriculture, goods manufacturing and construction tend to be

much less affected. The leisure and tourism sectors were shut down

almost completely in the spring, benefitted from only a short-lived and

partial rebound during the summer, and are now again subject to tight

restrictions. Countries where the tourism sector carries an important

weight in the economy, including Greece, Spain, Portugal and Croatia,

are therefore particularly affected, with negative consequences for the

speed of recovery and employment. Services such as tourism, restaurant,

and accommodation tend to be employment intensive and characterised by a

high share of low-skilled and temporary workers who frequently are less

covered by formal employment support schemes.

Figure 7 Gross value added, change between 2019-Q4 and 2020-Q2, EA and selected countries

Note: *Wholesale and retail trade, transport,

accommodation and food service activities; arts, entertainment and

recreation. Red line for euro area average. Figures in brackets are

shares of a sector in euro area gross value added.

Source: DG ECFIN.

Figure 8 GDP levels compared to 2019-Q4

Note: No GDP quarterly forecasts are reported for CY, EL, MY and LU.

Source: DG ECFIN.

- Third, the economic and social consequences of the pandemic will

be felt well beyond the forecast horizon. The combination of the deep

drop in economic activity with the necessary massive fiscal support put

in place by all member states is leading to a surge in general

government deficits and debt levels. According to the autumn forecast,

the average general government deficit in the EU will rise from 0.5% of

GDP in 2019 to 8.4% this year before starting to decline again and the

public debt ratio will rise above 100% of GDP for the euro area as a

whole. The European corporate sector is seeing its equity base eroding,

with knock on effect on investment and the quality of bank assets.

Labour markets will also take time to recover. This means that continued

policy support is essential to limit permanent damage to the economy.

Beyond the immediate crisis response, policies should be put in place to

support potential growth in order to make sure that our economies can

generate the jobs and revenues needed for the future.

Policy matters

In contrast to the previous crisis, the economic policy response in

the EU has been swift, sizeable and coordinated. The ECB reacted

immediately with a very sizeable Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme

(PEPP). The Commission triggered the activation of the ‘general escape

clause’ in the Stability and Growth Pact to allow member states to

provide a strong fiscal response to the crisis.

Rapid agreements were also reached on a number of important EU

support instruments for citizens, companies and economies. These

included the unlocking and frontloading of €37 billion in unallocated

cohesion policy funding (the Corona Response Investment Initiative) and

the creation of the temporary €100 billion loan instrument SURE

(‘Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency’). SURE enables

member states, in particular those with relatively high borrowing

costs, to provide necessary income support to more workers and for

longer than would have otherwise been possible.

Most importantly, the European Council in July reached a landmark

agreement on the on the €750 billion Next Generation EU (NGEU)

programme. This strong demonstration of European solidarity and resolve

has cushioned the shock of the pandemic on businesses, people and

financial markets. It has kept people in their jobs, businesses open,

and financial markets calm, limiting the damage to the economy.

With the pandemic flaring up, the key task of economic policy makers

is to limit uncertainty. In the current juncture, this means above all a

rapid approval and a speedy implementation of Next Generation EU. We

are ready.

References

Battistini, N and G Stoevsky (2020), “Alternative scenarios for the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on economic activity in the euro area”, ECB Economic Bulletin 3: 25-30 (Box 1)

Botelho, V, A Consolo and A Dias da Silva (2020), “A preliminary assessment of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the euro area labour market”, ECB Economic Bulletin 5: 51-56 (Box 5).

European Commission (DG ECFIN) (2020), European Economic Forecast – Spring 2020. Institutional Paper 125

Hale, T et al. (2020), “Variation in government responses to COVID-19”, Blavatnik School of Government Working Papers 32 (Version 8.0), University of Oxford, October.

IMF (2000), World Economic Outlook, October 2020, Chapter 2.

Kozlowski, J, L Veldkamp and V Venkateswaran (2020), “Scarring Body and Mind: The Long-Term Belief-Scarring Effects of COVID-19”, NBER Working Paper 27439.

Pfeiffer, P, W Roeger and J in ’t Veld (2020), “The COVID19-Pandemic in the EU: Macroeconomic transmission and economic policy response”, European Economy Discussion Paper 127 (European Commission, DG ECFIN), July.