Initial portfolio investment reverted quickly and intra-euro area

cross-border portfolio investment exhibited low volatility. Only

cross-border public flows have been limited. This suggests that the

provision of unprecedented policy support has prevented private

risk-sharing channels from collapsing, reducing the risk of a sudden

stop in cross-border financial flows and a further exacerbation of the

crisis.

The COVID-19 crisis represents a unique litmus test for the

European Monetary Union’s (EMU) risk-sharing capacities in allowing us

to assess whether the institutional progress made since the global

crisis and the subsequent euro area sovereign debt crisis has borne any

fruit.

Despite the progress in recent years, the European banking and

capital markets unions are still incomplete. The decentralized nature of

European fiscal policies has historically been an impediment to

increasing and more resilient financial integration and stability in the

EMU (Bénasse-Quéré et al. 2018, Constâncio 2018 and Berger et al.

2018). Enhancing the EMU’s private and public risk-sharing capacities

has therefore been a central element of the policy debate on the

euro-area reform (Pisani-Ferry and Zettelmeyer 2019).

The COVID-19 crisis has unique characteristics, and it is not over

yet. While definitive answers can thus not yet be provided, we offer

some preliminary – but important – policy insights on the evolution of

risk-sharing among the EMU countries during the pandemic.

The case for intra-euro area risk sharing during the crisis

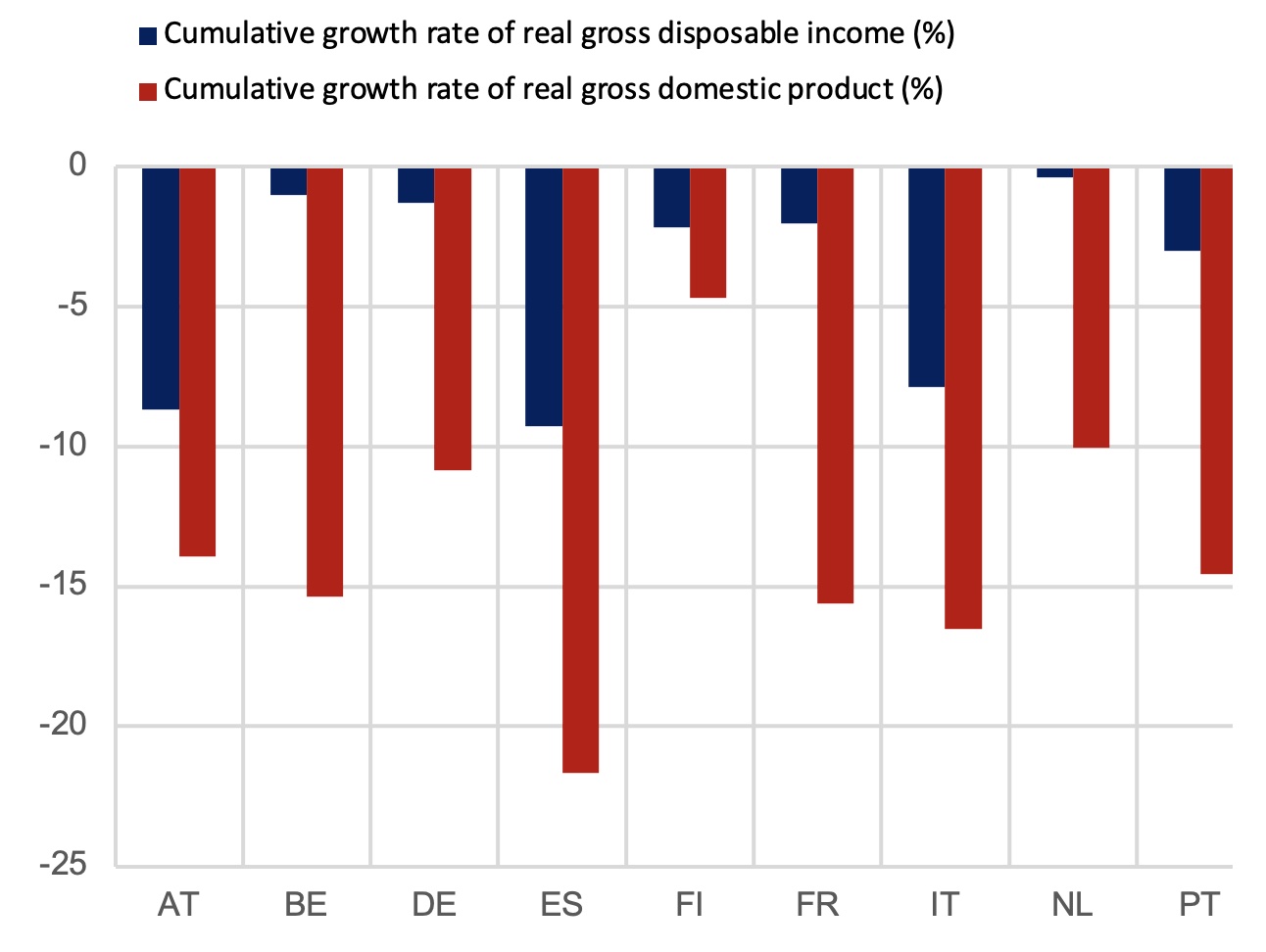

Given the common source of the COVID-19 crisis, one might prima facie

expect only limited room for cross-country risk-sharing among euro area

countries. Yet, despite its common cause, the economic fallout from the

COVID-19 pandemic has been quite heterogeneous across euro area

countries (see Figure 1), leaving room for cross-border risk-sharing.

Figure 1 Level and dispersion of growth rates of

real GDP and real gross disposable income (quarterly data, top panel: Q4

2019 – Q2 2020, bottom panel: Q1 2019 – Q2 2020)

Source: Authors’ calculations using Eurostat data:

Notes:

The top panel shows the cumulative growth rates of the real GDP and

real gross disposable income for Austria, Belgium, Germany, Spain,

Finland, France, Italy, Netherlands, and Portugal from Q4 2019 to Q2

2020. For the other EMU countries gross disposable income data for

2020Q2 is not yet available. The bottom panel shows the dispersion,

measured as the standard deviation, of the quarterly real gross domestic

product growth rate and the quarterly real gross disposable income

growth rate across the same set of countries.

As shown by Dossche and Zlatanos (2020), the strict health measures

taken in response to the spread of COVID-19 prevented households from

consuming a large share of their normal consumption basket. Therefore,

the procedure introduced by Asdrubali et al. (1996) and often used to

analyse risk-sharing within the euro area cannot be applied in the

current context. We thus focus on income risk-sharing (or income

smoothing), as opposed to consumption risk-sharing. In other words, we

look at the ability to separate a country’s change in gross national

income from changes in its output.

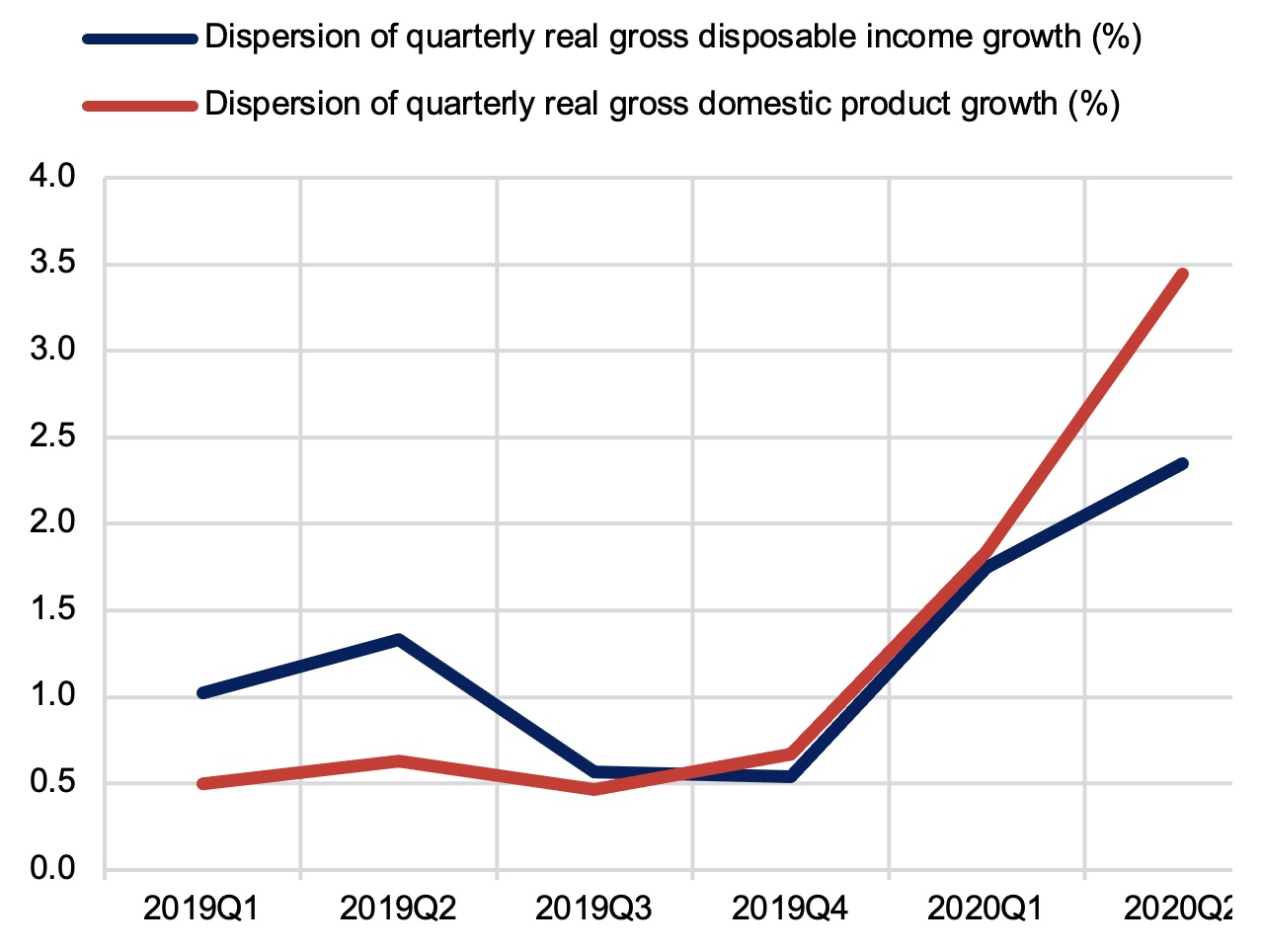

How has income risk-sharing evolved during the COVID-19 crisis?

We first look at the contemporaneous co-movement between disposable

income and output across euro area countries using a 12-quarter

rolling-window panel and adapting the methodology usually employed for

consumption risk sharing (ECB 2016). The results suggest that the amount

of income risk-sharing has been relatively stable over recent years,

albeit at low levels. Including the first six months of the current

crisis in the two most recent estimation windows does not lead to a

significant deterioration in the point estimate of income risk-sharing

(Figure 2). This suggests that the overall income risk-sharing among

euro area countries has been resilient so far throughout this crisis.

Figure 2 Comovement of disposable income and output in the euro area (percentage)

Source: Authors’ calculations using Eurostat data.

Notes:

The chart plots point estimates (dots) and confidence intervals

(whiskers) from a panel regression of changes in country per capita

gross disposable income on changes in country per capita GDP. Each dot

and whisker are estimated for data from the twelve quarters preceding

the time indicated on the horizontal axis (rolling window). Ireland is

excluded due to the major change in its GDP reporting in 2015. The

analysis is based on the following countries: Austria, Belgium, Germany,

Spain, Finland, France, Italy, Netherlands, and Portugal. For the other

EMU countries gross disposable income data for 2020Q2 is not yet

available.

Risk sharing channels during the crisis

In a second step, we examine the financial flows through which risk

sharing should operate – i.e. cross-border private and public financial

flows.

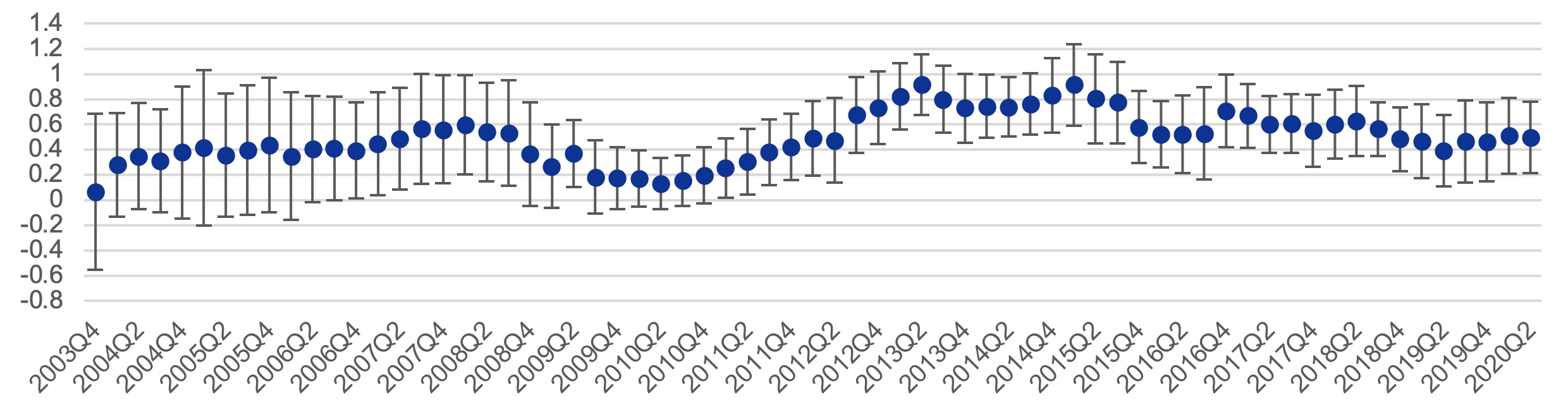

Figure 3 shows that intra-euro area cross-border private flows

exhibited a high degree of resilience during the peak of the COVID-19

crisis. This is in sharp contrast with the experience during the

previous crisis, when some euro area countries experienced a sudden stop

in capital inflows (Gros and Alcidi 2013). While a strong outflow in

intra-euro area portfolio investments was recorded in March 2020, this

has been more than compensated by strong inflows in the following months

(see Figure 3). Looking at intra-euro area direct investments, the

flows appear less volatile, in line with the prediction of the

literature (ECB 2016). The same pattern can be seen when looking at

financial flows coming from outside the euro area (Lane 2020).

Figure 3 Intra-euro area cross border financial flows

Source: Authors’ calculations on ECB data.

Intra-euro area cross-border public flows were limited during the

first peak of the crisis between March and June 2020. The depth of the

COVID-19 shock triggered sizable fiscal responses at the national level,

leading to a drastic deterioration of fiscal deficits. This is not new,

and quite in line with the previous global crisis and euro area crises

(Milano and Reichlin 2017).

Nevertheless, from the very onset of the COVID-19 crisis, there was a

clear recognition that national measures should be supported by a

common financing programme at the European level. This marked a key

difference compared to the previous crises.

Already in April, the European Commission rapidly set up the

Coronavirus Response Investment Initiative to provide €8 billion in

immediate liquidity to the countries in greatest need. Not long after,

the three EU safety nets, worth €540 billion, were established. Two of

the three schemes – the Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an

Emergency (SURE) and the European Stability Mechanism’s Pandemic Crisis

Support credit line – provide loan-based support to governments. The

third pillar – the pan-European guarantee fund of the European

Investment Bank – provides support to companies. As this fund is

expected to make losses over the course of its operations (at 20% in net

terms; see Eurostat 2020), it is expected to produce direct

cross-border transfers.

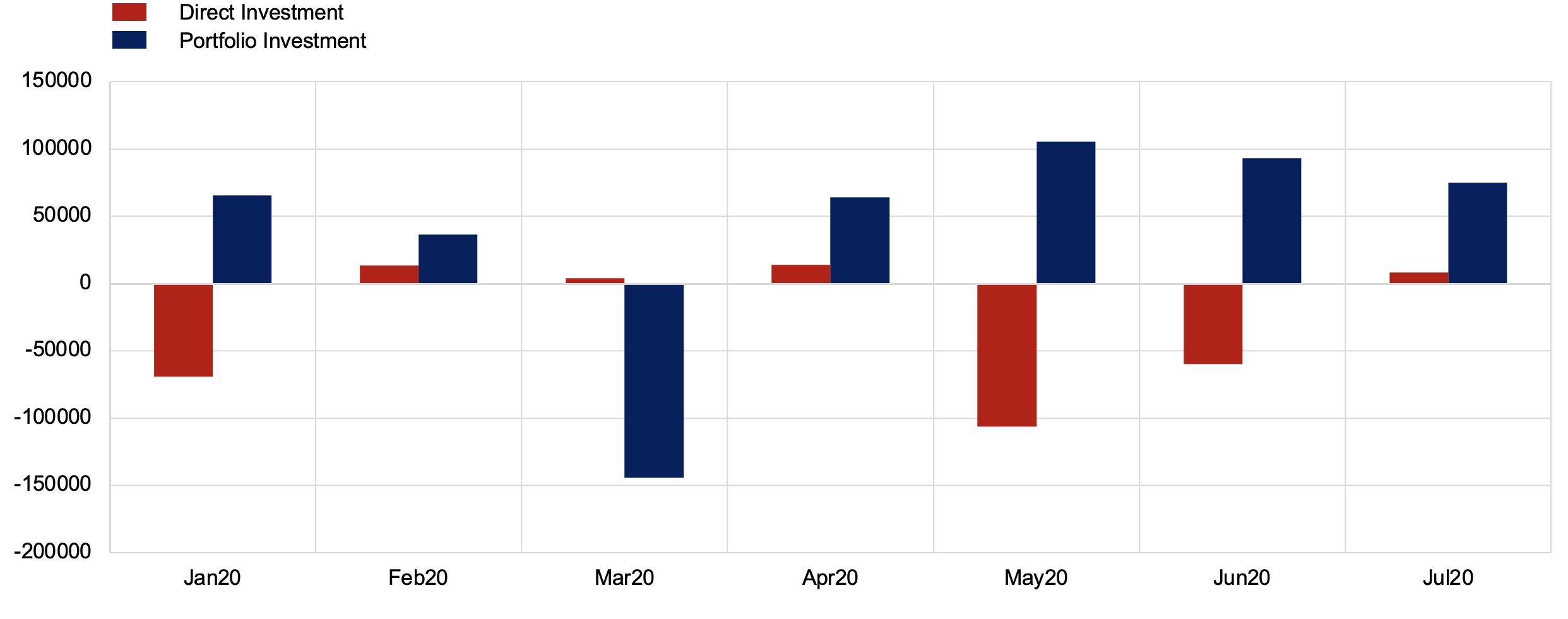

The most sizable programme of cross-border public support will be the

Next Generation EU. The agreed distribution of funds will imply

sizeable net financial support for those euro-area countries which face

the biggest economic and fiscal challenges after the pandemic (ECB

2020a). The loan-based component will provide additional risk sharing

via cross-border borrowing whereas the grant component will constitute

of direct fiscal transfers. While the majority of the EU support will be

provided only once the peak of the pandemic will be over, the fact that

EU funding could act as a substitute for sovereign issuance in the

future (especially for those countries facing the biggest economic and

fiscal challenges) has played an important stabilising role and has been

seen as a contributory factor to the decline in these countries’

sovereign yields.

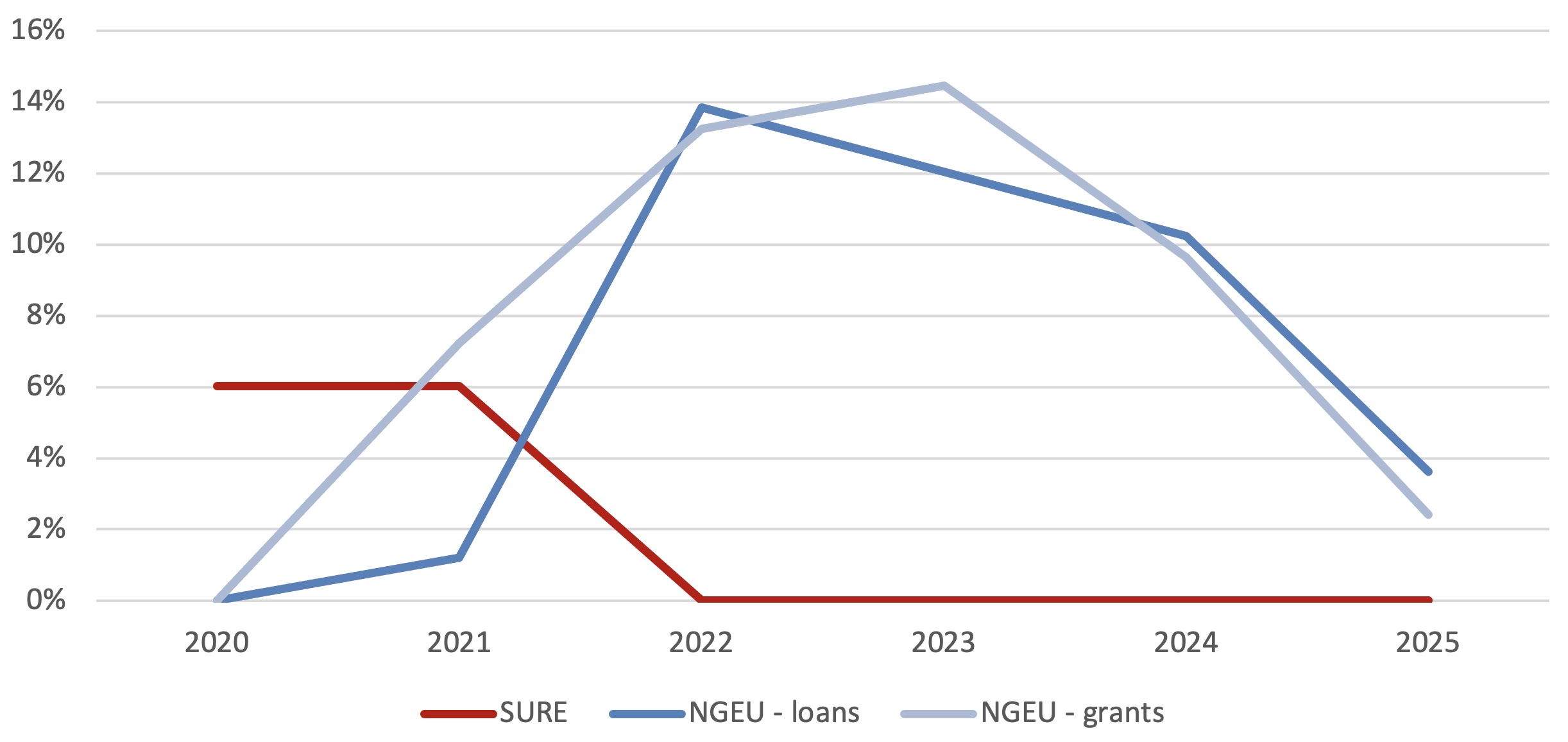

Figure 4 Evolution of the EU-budget based support (% of total support)

Source: authors’ calculations on Commission RRF proposal and European Council conclusions.

Notes:

This estimate is based on several assumptions on how the expected

commitments in loans and grants translate into payments over the years.

It also assumes that 100% of the RRF loans will be used be used by

Member States.

Preliminary – yet important – policy considerations

As the COVID-19 crisis is not yet over, it is only possible to draw some preliminary policy considerations at this stage.

While some challenges for the resilience of the euro area financial

integration emerged during the outbreak of the crisis (Borgioli et al.

2020), the unprecedented amount of fiscal and monetary policy measures

provided timely support to the economies, stabilising financial markets

and preventing private risk-sharing channels from collapsing. This, in

turn, has reduced the risk of ‘sudden stops’ that would have further

exacerbated the crisis. The mistakes that have characterised past

episodes have been avoided thus far.

The key questions are now whether the unprecedented policy response

to the ongoing crisis could provide the momentum for an ambitious

overhaul of the EMU financial and fiscal architecture that would be

conducive to more sustainable private and public risk sharing within the

euro area.

Authors’ note: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Central Bank.

References

Asdrubali, P, B Sorensen and O Yosha (1996), “Channels of interstate risk sharing: United States 1963‑1990”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 111(4): 1081‑1110.

Beck, R, L Dedola, A Giovannini and A Popov (2016), “Financial

integration and risk sharing in a monetary union”, ECB Report Financial

Integration in Europe, Special Feature A.

Bénassy-Quéré, A, M Brunnermeier, H Enderlein, E Farhi, M Fratzscher,

C Fuest, P-O Gourinchas, P Martin, J Pisani-Ferry, H Rey, I Schnabel,N

Véron, B Weder di Mauro, J Zettelmeyer (2018), “Reconciling risk sharing with market discipline: A constructive approach to euro area reform”, CEPR Policy Insight No 91.

Berger, H, G Dell'Ariccia and M Obstfeld (2018), “Revisiting the

Economic Case for Fiscal Union in the Euro Area”, IMF Departmental Paper

No 18/03, International Monetary Fund.

Borgioli, S, C-W Horn, U Kochanska, P Molitor, F P Mongelli, E Mulder, A Zito (2020), “European financial integration during the COVID-19 crisis: Insights from a new indicator”, VoxEU.org, 3 December.

Constâncio, V (2018), “Why EMU requires more financial integration”,

Speech at joint conference of the European Commission and European

Central Bank, Frankfurt am Main, 3 May.

Dossche, M and S Zlatanos (2020), “COVID-19 and the increase in

household savings: precautionary or forced?“, ECB Economic Bulletin

Issue 6.

ECB (2016), “ECB Financial Integration Report 2016”, April.

ECB (2020a), “Financial Integration and Structure in the Euro Area”, March.

Eurostat (2020), “Methodological note Guidance Note on the recording of the future EIB Pan-European Guarantee Fund”.

Giovannini, A, S Hauptmeier, N Leiner-Killinger and V Valenta (2020),

“The fiscal implications of the EU’s recovery package“, ECB Economic

Bulletin Issue 6.

Gros, D and A Alcidi (2013), “Country adjustment to a ‘sudden stop’:

Does the euro make a difference?”, European Commission Economic Papers

492, April.

Haroutunian, S, S Hauptmeier and N Leiner-Killinger (2020), “The

COVID-19 crisis and its implications for fiscal policies”, ECB Economic

Bulletin Issue 4.

Lane, P (2020) “International flows and the pandemic: evidence from

the euro area”, Bank of England / Banque de France / IMF / OECD workshop

on ‘International capital flows and financial policies’, 21 October.

Milano, V and P Reichlin (2017), “Risk sharing across the US and Eurozone: The role of public institutions”, VoxEU.org, 23 January.

Pisani-Ferry, J and J Zettelmeyer (2019), Risk Sharing Plus Market Discipline: A New Paradigm for Euro Area Reform? A Debate, VoxEU eBook.