The 2020 ECB Forum on Central Banking addressed some key issues from the ongoing monetary policy strategy review and embedded them in discussions of major structural changes in advanced economies and the post-COVID recovery.

In this column, two of the organisers highlight some of the main points

from the papers and debates, including whether globalisation is

reversing, implications of climate change, options for formulating the

ECB's inflation aim, challenges with informal monetary policy

communication, relationships between financial stability and monetary

policy, how to make a monetary policy framework robust to deflation or

inflation traps and the role of fiscal policy for the recovery from the

pandemic.

The 2020 ECB Forum was one of the “ECB listens” events through which

the ECB collects the views of relevant outside parties on its monetary

policy framework. Policymakers, academics and market economists debated

the implications of selected key structural changes that have a bearing

for how monetary policy works in the euro area, combined with

discussions on core topics featuring in the strategy review. We group

some of the main issues debated in five sections below. All papers,

discussions and speeches can be found in the conference e-book (ECB 2021). Video recordings of all sessions are available on the ECB website.

Fundamental structural changes in the world economy: ‘Slowbalisation’ and climate change

One of the key structural changes in the world economy over the last

decades was globalisation. But since the Global Financial Crisis and

with the rise of populism, the issue has emerged as to whether this

process is reversing to ‘de-globalisation’. Pol Antras (in Antras 2021)

argues that international trade and supply chains have slowed but not

reversed (‘slowbalisation’) and may be regarded as not likely to turn to

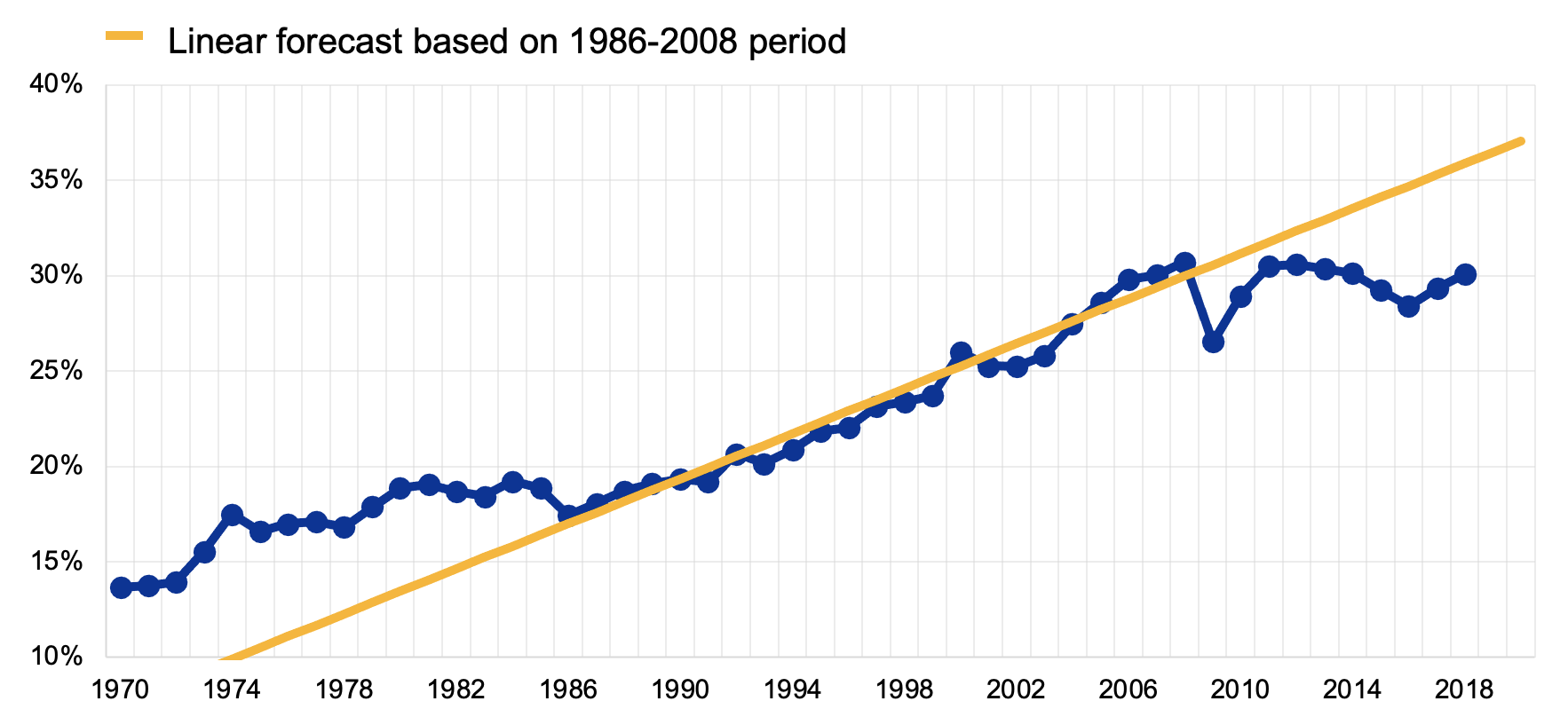

de-globalisation. The backward-looking part is illustrated in Figure 1,

which shows that after a period of very fast ‘hyperglobalisation’

between the mid-1980s and 2008, the share of world trade in world GDP

has stayed roughly constant.

Figure 1 World trade relative to world GDP (1970-2018)

Note: Trade is defined as the sum of exports and imports of goods and services.

Source: Antras (2021), based on World Bank’s World Development Indicators (link).

Looking forward, Antras argues that two out of three main factors

that explained ‘hyperglobalisation’ are unlikely to reverse. First, new

technologies will continue to foster trade, because those substituting

(foreign) labour (such as robotisation or 3D printing) still generate

increased demand for traded goods (such as machines or IT parts).

Second, the high sunk costs of establishing global supply chains make

them resilient to temporary shocks and re-shoring only attractive for

very persistent shocks. The only hyperglobalisation factor risking to

reverse is multilateral trade liberalisation. To the extent that agents

perceive the COVID-19 pandemic as temporary, it is unlikely to become a

persistent de-globalisation force.

Susan Lund added that China rotating from exports to domestic

consumption and building domestic supply chains can account for most of

the global trade slowdown over the last decade (Lund 2021). As both

reflect economic development, it may be regarded as a positive story,

one other emerging economies may also go through in the future.

Climate change is likely to set in motion another set of major

structural changes in the world economy. But Frederick van der Ploeg

strongly warns of the great risk that policy responses will be too timid

and too late, implying an unsmooth carbon transition with stranded

assets and financial instability (van der Ploeg 2021). A sudden shift in

climate policy or a technological breakthrough can lead to sudden

changes in the market valuation of firms (so-called tipping events).

Figure 2 (taken from van der Ploeg 2018) illustrates that the route of a

cap to global warming taken by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate

Change (dotted line) would increase the carbon price (and therefore

reduce carbon emissions and increase renewables) much faster than

economists' preferred approach of pricing carbon at its estimated social

costs (solid line). The reason is that economists' ‘Pigouvian’ approach

does not take peak temperature constraints into account, and thus

prices do not have to rise so fiercely under it....

more at Vox

© VoxEU.org

Key

Hover over the blue highlighted

text to view the acronym meaning

Hover

over these icons for more information

Comments:

No Comments for this Article