At the end of 2019 the European Systemic Risk Board General Board mandated a Task Force on Low Interest Rates to revisit the ESRB’s 2016 report on “Macroprudential policy issues arising from low interest rates and structural changes in the EU financial system”, assess subsequent developments, compare these to the risks identified in the report, and assess whether new sources of systemic risk have emerged.

Furthermore,

the Task Force was mandated to review progress in relation to the policy

proposals in the earlier report, as well as propose possible new policy

actions aimed at mitigating potential systemic risks. As this column

discusses, the new report finds that the low interest rate environment

continues to pose risks for financial stability. For instance, since

2016, search-for-yield behaviour has intensified in the banking and

investment fund sectors, and some business models are proving

unsustainable. To address these sources of risk and vulnerabilities, the

report puts forward a wide range of policy options.

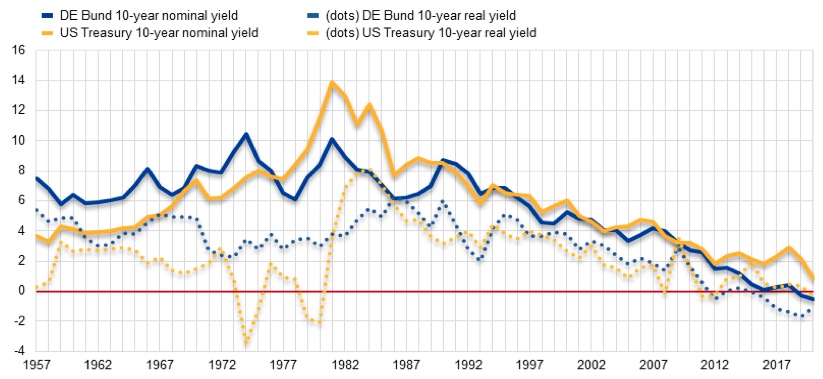

Nominal and real

interest rates in the major advanced economies, short-term and

long-term, have trended downwards since the early 1980s. We see this in

Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1 Short-term nominal and real interest rates in Germany and the US, 1965-2020 (%)

Source: OECD and ESRB calculations.

Note:

Short-term interest rates are based on three-month money market rates.

Real rates are calculated by subtracting the annual CPI inflation rate.

Figure 2 Nominal and real ten-year government bond yields in Germany and the US, 1957-2020 (%)

Source: OECD and ESRB calculations.

Note:

Yields are based on ten-year constant maturity government bond yields.

Real yields are calculated by subtracting the annual CPI inflation rate.

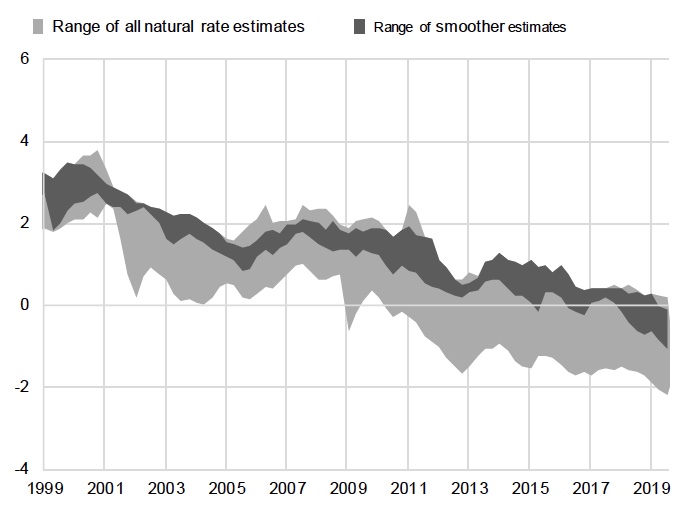

The ‘natural’ or

‘neutral’ equilibrium real interest rate R* that would support full

employment at stable and low inflation is not directly observable. Many

efforts to estimate it reach similar results, however, as shown for the

euro area in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Estimates of euro area equilibrium real interest rate, Q1 1999 to Q4 2019 (%)

Source: Schnabel (2020).

Notes:

Ranges span point estimates across models to reflect model uncertainty

and no other source or R* uncertainty. The dark shaded area highlights

smoother R* estimates that are statistically less affected by cyclical

movements in the real rate of interest. Latest observation: Q4 2019.

With low and stable

inflation, the decline in R* has forced policy rates down towards their

effective lower bound. This now appears to be somewhat though not much

below zero. Market rates too are very low. Whether policy rates or

market rates, the low interest rate environment (LIRE) has implications

for financial stability and therefore raises issues for macroprudential

policy.

The European

Systemic Risk Board (ESRB), which oversees macroprudential policy in the

EU, has just published a second report discussing macroprudential

policy issues arising from the LIRE in the EU financial system (ESRB

2021). This work began at the end of 2019 and builds on an earlier

report, which the ESRB published in 2016.

The time horizon for

our analysis is medium-term: five to ten years ahead. While the report

acknowledges cross-country heterogeneity, its focus is mainly on the EU

financial system as a whole and on interest rates in the EU.

The report begins with an analysis of how the LIRE has been driven mainly by structural factors, such as:

- demographic

developments including rising life expectancy and falling population

growth rates (Acemoglu and Johnson 2007, Backus et al. 2014, Aksoy et

al. 2019);

- falling (relative)

price of investment goods and the rising share of intangible investment

(Karabarbounis and Neiman 2014, Thwaites 2015);

- slowing pace of technological innovation (Gordon 2016);

- falling marginal product of capital (related to demography and technical progress) (Cochrane 2021);

- rising wealth and income inequality (Summers 2014, Rachel and Summers 2019)

- rising savings

rates in developing countries and the consequent rising demand for

assets issued by advanced economies (Bernanke 2005); and

- evolution of the consumption/wealth ratio (Gourinchas et al. 2020)

This literature

is related to the ‘secular stagnation’ hypothesis revived by Summers in

his speech at the IMF Research Conference in 2013. In addition,

regulatory changes and the more risk-averse positioning adopted by

financial institutions after the global financial crisis (GFC) have

further boosted the demand for safe assets, putting more downward

pressure on real interest rates and on risk premia. Many of these

developments (and the trend decline in R*) hold not just for the euro

area, but also for the US and Japan, and to some extent interest rates

are transmitted globally (the ‘global financial cycle’; see Rey 2013).

Two recent analyses

support ‘low for long’. Kiley (2020) reviews the literature and adds his

own econometric study, concluding: “A range of approaches to estimating

the equilibrium real interest rate confirm a pronounced downward trend

among advanced economies in the level of real short-term interest rates

likely to prevail over the longer term.” Gourinchas et al. (2020) agree:

“Our estimates indicate that short-term real risk-free rates are

expected to remain low or even negative for an extended period of time.”

But what about the

COVID-19 shock? The report acknowledges that contractionary monetary

policies (responding to a temporary rise in inflation) and increases in

term premia (due to a temporary surge of uncertainty) could increase

rates. If they were to occur, we would not expect such effects to be

lasting. As long as the structural factors that have exerted downward

pressure on the natural rate of interest persist, the LIRE will remain

in place, at least in the medium term, according to the report. In fact,

the report’s detailed overview of the effects of the COVID-19 shock

concludes that it may have increased the probability and persistence of a

‘low-for-long’ scenario – so ‘even lower for even longer’.

The risk analysis of the report identifies four key areas of concern in the LIRE:

- the profitability and resilience of banks,

as the LIRE accentuates the negative effects of existing structural

problems in the EU banking sector, including overcapacity and cost

inefficiencies;

- the indebtedness and viability of borrowers, as the LIRE facilitates higher leverage and encourages search-for-yield behaviour;

- systemic liquidity risk, as the LIRE and structural changes have made the financial system more sensitive to market shocks;

- the sustainability of the business models of insurers and pension funds offering longer-term return guarantees, as they experience increasing pressures in the LIRE.

More at Vox

© VoxEU.org

Key

Hover over the blue highlighted

text to view the acronym meaning

Hover

over these icons for more information

Comments:

No Comments for this Article