The freezing of Russian foreign exchange reserves will have long-term and systemic consequences. This column argues that the dominant role of the dollar as a reserve currency will be unaffected. No other country can provide.. a large, liquid government bond market and a fully open capital account.

Sanctions may have significant long-term effects on the demand for reserves. Countries may reduce their dependence on reserves by limiting their exposure to financial shocks and partially restricting capital movements. The international monetary system may evolve towards to a new architecture, where cross-border financial integration is reduced.

Following

the invasion of Ukraine, the sanctions taken against Russia have been

unprecedented in scale and, above all, in scope. For the first time in

recent history, the foreign exchange reserves held by a major central

bank have been frozen. Reactions by Russian authorities show that this

was totally unexpected on their part (Berner et al. 2022). This column

presents some preliminary thoughts on the potential long-term and

systemic consequences in a context of geopolitical rivalry and

increasing ‘deglobalisation’, at least in respect to financial

transactions.

Sanctions and the dollar

A first question to

consider is whether the status of the dollar as the dominant

international currency could be put in doubt or risk. Our answer is

negative for three reasons.

- The freeze is

taking place in a situation that may be perceived as truly exceptional:

an armed conflict triggered by the invasion carried out by a major

country. No one would expect standard financial relations and

arrangements to hold in those circumstances. In comparable situations,

such as Japan’s war in Asia from 1937, cross-border payments were

eventually blocked. Gold owned by countries occupied or in war was not

handed over to the aggressor by the central banks that held it. Thus,

France and Britain refused to hand over the reserves of the Baltic

countries annexed by the Soviet Union in 1940. These are extreme and

rare circumstances.

- All actions taken

by the US authorities over the last decades demonstrate their commitment

to promote and preserve the dollar as a safe asset. Numerous facilities

have been deployed by the Federal Reserve to ensure the liquidity of

the Treasury market – some of them specially designed for official

foreign holders. The implicit government guarantee benefitting Fanny Mae

and Freddie Mac (which serve as a major instrument of foreign exchange

reserves) has been reaffirmed when necessary. With the possible

exception of the Trump administration, successive US Treasury

secretaries have been adamant that “a strong dollar is in the interest

of the United States”.

- Finally, attractive

alternatives to the US dollar do not exist and hence no realistic

diversification instrument is available. The power of the US to impose

sanctions derives directly from the central role of the dollar. For any

international corporation or financial institution, life without the

dollar is currently impossible. Therefore, any of their operation falls

potentially under US jurisdiction. All will remain under the reach of

sanctions so long as the dollar remains essential. Avoiding and

resisting sanctions means finding alternatives to the dollar. We are

therefore drawn back to an old, and still very acute question: are there

such alternatives?

International money, old and new

Money is about scale

and externalities. They come in two forms: network externalities – the

more people accept a currency the better it is as a medium of exchange;

and liquidity externalities – a true store of value remains tradable and

valuable in times of need (Brunnermeier et al. 2022). In the current

world economy, a crucial question concerns the causality between those

two functions.

The dominant

currency paradigm (Gopinath and Stein 2021) mainly attributes the

essentiality of the dollar to its role in global payments and finance –

emphasising the medium of exchange role and its function as a vehicle

currency for international financial flows. In the same vein,

Eichengreen (2010), based on his analysis of history of the interwar

period, sees a logical sequencing in the emergence of a global currency:

(1) invoicing and settling trade, (2) use in private financial

transactions (vehicle currency), (3) use by central banks as reserves.

If that sequence is

still valid, there are real prospects of alternative reserve currencies

emerging. China is the world’s major trading power. It has leverage to

push for the use of its currency as a medium of exchange and unit of

account. It could exploit its advance in the development of digital

currencies. A possible scenario would see both Alipay and Tencent expand

their international operations, progressively shifting their

denomination from local currencies to the renminbi. China is the most

advanced in developing a central bank digital currency. The introduction

of the e-yuan, already past its pilot phase, is often interpreted as an

offensive move to promote the RMB internationalisation.

Another, somehow

opposite, approach attributes the dollar dominance to its unique role as

a store of value, being the ultimate safe asset. There is nowhere else

to park several hundred billion with almost total security and

liquidity. That function is central in a financially globalised world

where both private and public entities must protect their liquidity.

From that role as a store of value, other functions derive, reversing

the causality that may have prevailed in other periods. Because it is a

reserve asset, it is convenient to also use the dollar for invoicing and

payments. It serves as a global unit of account. Significantly, even

China overseas lending by official entities is still 70% denominated in

dollars and only 10% in renminbi.

If, as we think,

that second approach is correct, no other money is positioned to

dislodge the dollar in the foreseeable future. Being a reserve currency

certainly brings privileges and power. It is also very demanding. Two

major requirements must be met, which no other country can do: a large

and liquid Treasury bond market (which Europe does not currently have)

and a fully and unconditionally open capital account (which China will

not have). Localised swap and barter agreements, such as developed by

China, can help but will not dispense of those two basic requirements.

(A columnist recently remarked that a credit line in renminbi is

financially equivalent to being fluent in Esperanto).

A quick look at other possible mentioned alternatives confirms that diagnosis:

- Currencies such as the Australian dollar are mentioned as possible reserve instruments.1 While fully open and accessible, the size of the Australian Treasury Bond market is only 2.5% of the US.

- There have been

recurrent attempts to make the Special Drawing Rights into a genuine

alternative to reserves – a course actively promoted by China in the

aftermath of the Global Crisis (Zhou 2009). They have largely stalled,

for reasons of size and accessibility (the possible use of Special

Drawing Rights is closely restricted by design).

- Some observers

stress the potentialities of cryptocurrencies, pointing to their role to

channel funds to Ukraine after the Russian invasion (Danielsson 2022).

However, they have no ability to process transactions on a large scale

(daily amounts mentioned in relation with Ukraine are in the tens of

millions of dollars). Despite some fascinating technological features,

cryptocurrencies are even further from having any significant role as

reserves. Managers are aware of the peculiarities of these money

systems. Their day-to-day functioning relies on the initiatives and

incentives of private operators, whose activity is purely voluntary and

profit-motivated. It is doubtful that they would entrust public reserves

to groups of ‘miners’ scattered all over the world, with a

non-negligible proportion having migrated to Kazakhstan after having

been prohibited to operate in China.

Globalisation and the demand for reserves

Sanctions may still

have significant longer-term effects – not on the composition, but on

the demand for reserves. The international monetary system may

ultimately adjust by moving to a new architecture, where financial

integration is reduced and, consequently, the need for reserves is

smaller.

Leaving aside the

reciprocal relation between the US and China – famously qualified by

Larry Summers as a “financial balance of terror” – it is useful to

consider the situation

of other emerging

countries. Around twenty countries have foreign exchange reserves above

$100 billion, most of them emerging economies. Borrowing from the

finance and climate literature, those countries clearly face a new ‘tail

risk’ of sanctions, with a very low probability but very high impact.

The same climate literature tells us that one cannot diversify against

those risks. The only way to buy insurance is to reduce one’s exposure.

In climate, it means bringing down CO2 emissions and

concentrations to low levels. For emerging economies, it means reducing

the need for (and dependence upon) foreign exchange reserves.

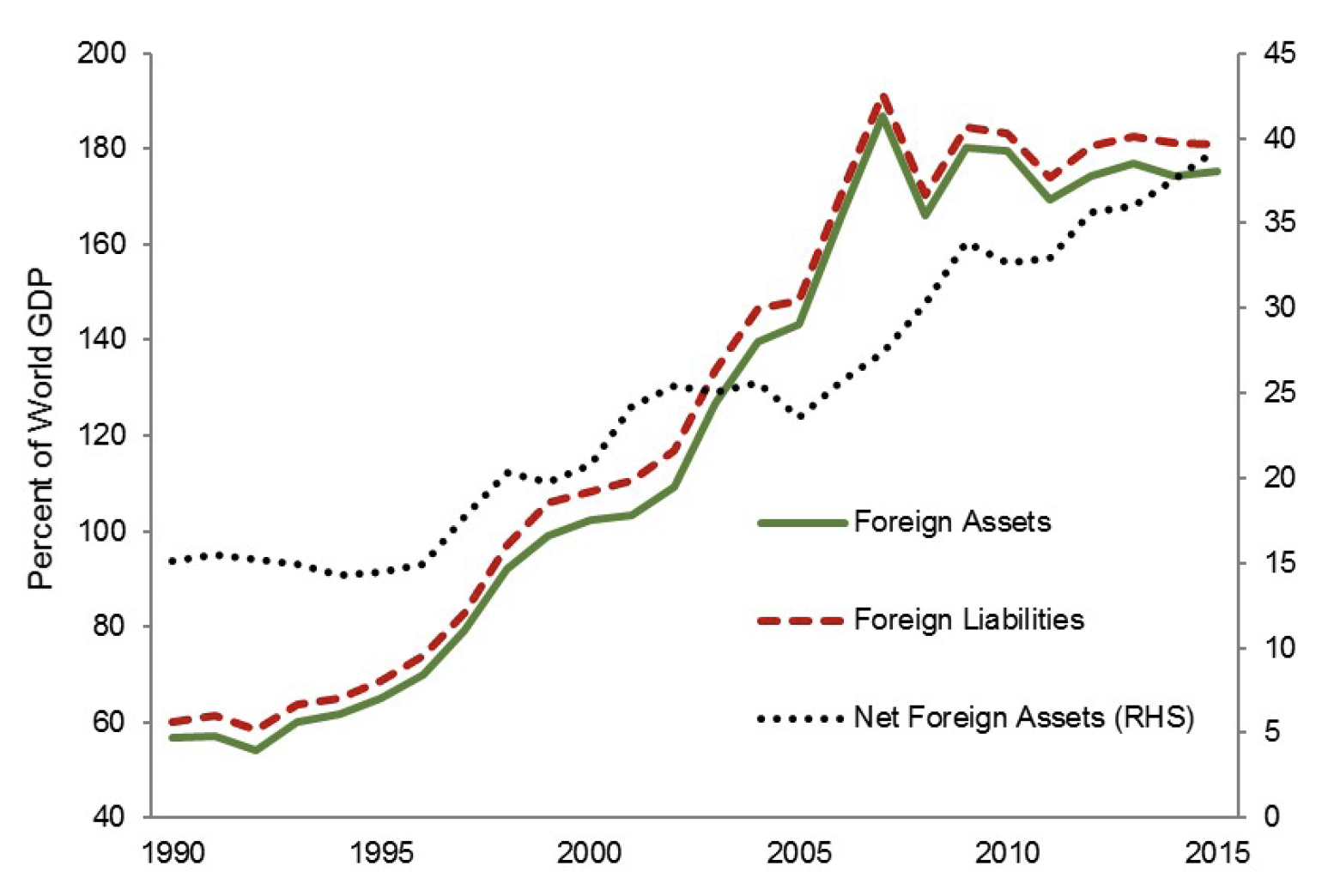

There has been a

constant increase in foreign exchange reserves until 2015 and a

plateauing since then. That evolution almost mirrors (with a lag of a

few years) the trends in gross cross-border capital flows and

international exposures, which expanded until 2010 and then stabilised

as a consequence of the Global Crisis.

Figure 1

a) Foreign exchange reserves

Source: ECB Economic Bulletin issue 7/2019.

b) Gross international assets and liabilities

Source: Adler and Garcia-Macia (2018).

This is not a

coincidence. With the exception of China, countries’ demand for reserves

is a direct result of their financial integration with the world.

Reserves are traditionally viewed as a tool for exchange rate

management. But they play a broader role. In many emerging economies,

the productive and financial sector is partially ‘dollarised’. As a

consequence of capital account liberalisation, both corporate and

financial institutions are able to borrow and lend in foreign currency.

Consequently, they may be facing maturity and liquidity mismatch in

dollars. Foreign reserves allow central banks in those countries to act

as lenders of last resort in foreign currency and protect domestic, as

well as external, financial stability. This is the fundamental reason

why reserves have, over the two last decades, expanded to levels that

are impossible to explain and rationalise by traditional metrics of

trade and financial openness.

Those policy choices

may well be reversed if and when reserves are carrying new risks.

Financial globalisation had essentially come to a halt well before the

invasion of Ukraine.

New forms of

sanctions, even if very rare, may lead to a further retreat and

segmentation of the world financial system (Harding 2022).

Ultimately,

sanctions, and their implications, reveal a basic, and forgotten, truth:

the movement towards greater financial globalisation has been

underpinned by a long-term commonality of purposes, standards and

understanding between countries. By supplying a reserve currency (and

benefiting from it), by augmenting it in crisis moments such as 2008 or

2020 by swap lines, the US has provided the world with a global public

good (Wolf 2022): widespread access to a safe asset, which can be used

as a buffer against financial shocks. Whether that equilibrium can be

preserved in a geopolitically divided world is a major question for the

future.

Vox

© VoxEU.org

Key

Hover over the blue highlighted

text to view the acronym meaning

Hover

over these icons for more information

Comments:

No Comments for this Article