How European policymakers solve the policy mix trilemma of asymmetric fiscal rules, no central fiscal capacity and constrained monetary policy in the post-pandemic economy will define the resilience of the euro area in the face of future shocks and the transition to a more sustainable growth model.

In a new CEPR Policy Insight, the authors argue that moving to a structured vertical coordination between national and EU budgets would help ensure an adequate fiscal stance and avoid the overburdening of the single monetary policy.

During the past 13 years, the EU has undergone two major

‘existential’ crises: the Great Recession that reached the peak after

the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 and culminated with

the sovereign debt crisis of 2011-2012 (Reinhart and Felton 2008a,

2008b, Baldwin and Giavazzi 2015), and the COVID-19 crisis which erupted

in spring 2020 (Baldwin and Weder di Mauro 2020a, 2020b). It is now

largely acknowledged that the responses of the EU and its member states

were radically different between the two crises. During the Great

Recession, after an initial monetary and fiscal expansion, the focus

quickly turned to government debt sustainability and fiscal prudence to

reassure the markets, so that the onus of sustaining the economy fell

mainly on the shoulders of the ECB. Instead, during the pandemic a much

more forceful monetary and fiscal response was enacted. The ECB adopted

the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) and strengthened its

utilisation of other monetary tools, and national fiscal authorities

implemented sizeable fiscal expansions on the back of the suspension of

the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP)’s adjustment requirements via the

General Escape Clause (GEC) and the temporary state aid framework. Most

importantly, the Union agreed on a programme of direct support via the

EU multiannual balance, Next Generation EU (NGEU), with at its core the

Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF).

It is important to stress that, in the pandemic crisis, the

combination of national and EU budgets coupled with the rapid and

determined ECB measures have led to a more expansionary policy stance

compared to previous crisis episodes. Moreover, for the first time, the

EU rule-based framework has been complemented by direct policy support

at the central level. In CEPR Policy Insight 113,

we argue that this forceful policy response and, in particular, the

move to a more structured ‘vertical’ coordination between national and

EU fiscal policies has led to a more balanced policy mix and has, thus,

allowed the rapid absorption of the euro area’s dramatic recession and

favoured a strong bouncing back of its economy in the current year (Buti

and Messori 2021b).

The different policy stance between the two crises can be explained

by the different nature of the shocks and the learning from the past

failures (Buti 2020, Buti and Papacostantinou 2021). However, these

changes in the policy stance also raise fundamental issues.

Conceptually, in any currency area, policymakers need to supply an

‘adequate’ amount of cyclical stabilisation, either via the common

monetary policy, via fiscal policy at central or decentralised level,

or, most likely, via a combination of these different policies. Within

the Maastricht framework, policy authorities face what can be dubbed the

euro area’s “policy-mix trilemma”: one cannot have, at the same time,

(a) asymmetric fiscal rules of the Maastricht type, (b) monetary policy

constrained by the effective lower bound (ELB), and (c) no-central

fiscal capacity.

The Maastricht Treaty and, a fortiori, the SGP are

fundamentally asymmetric in their call to avoid excessive government

deficits without any constraint on the corresponding balance surpluses.

These rules ‘proscribe’ excessive government deficit even if this

entails a pro-cyclical fiscal behaviour, but do not have any

‘prescribing’ power over policies by countries with fiscal space. This

asymmetry reflects the ‘Brussels-Frankfurt consensus’ prevailing at the

time of the negotiations of Maastricht Treaty and of the SGP. The focus

was on the risk of a deficit bias aggravated by the common pool problem

(Buti and Sapir 1998, Buti and Gaspar 2021).

The Commission and the EU Council could credibly enforce the

Excessive Deficit Procedure in the absence of a central fiscal capacity

only if monetary policy had an unconstrained space to respond to shocks.

This is not the case in the euro area, because the monetary policy is

limited by the ELB on interest rates. Hence, the fiscal stabilisation

should be necessarily supplied either by the violation of the Maastricht

fiscal requirements or by the setting up of a central fiscal response. A

related implication is that the proscribing (as opposed to prescribing)

nature of Maastricht fiscal rules makes it exceedingly difficult to

achieve the right fiscal stance for the EU solely via ‘horizontal’

coordination of national fiscal policies. The experiences of the last

decade before the pandemic shock has shown that either the EU fiscal

stance was not adequate, or the achievement of a satisfactory fiscal

stance took place, most of the times, via a wrong distribution of

national fiscal positions – i.e. too restrictive in countries with

fiscal space and too relaxed in countries with high government deficits

and debts.

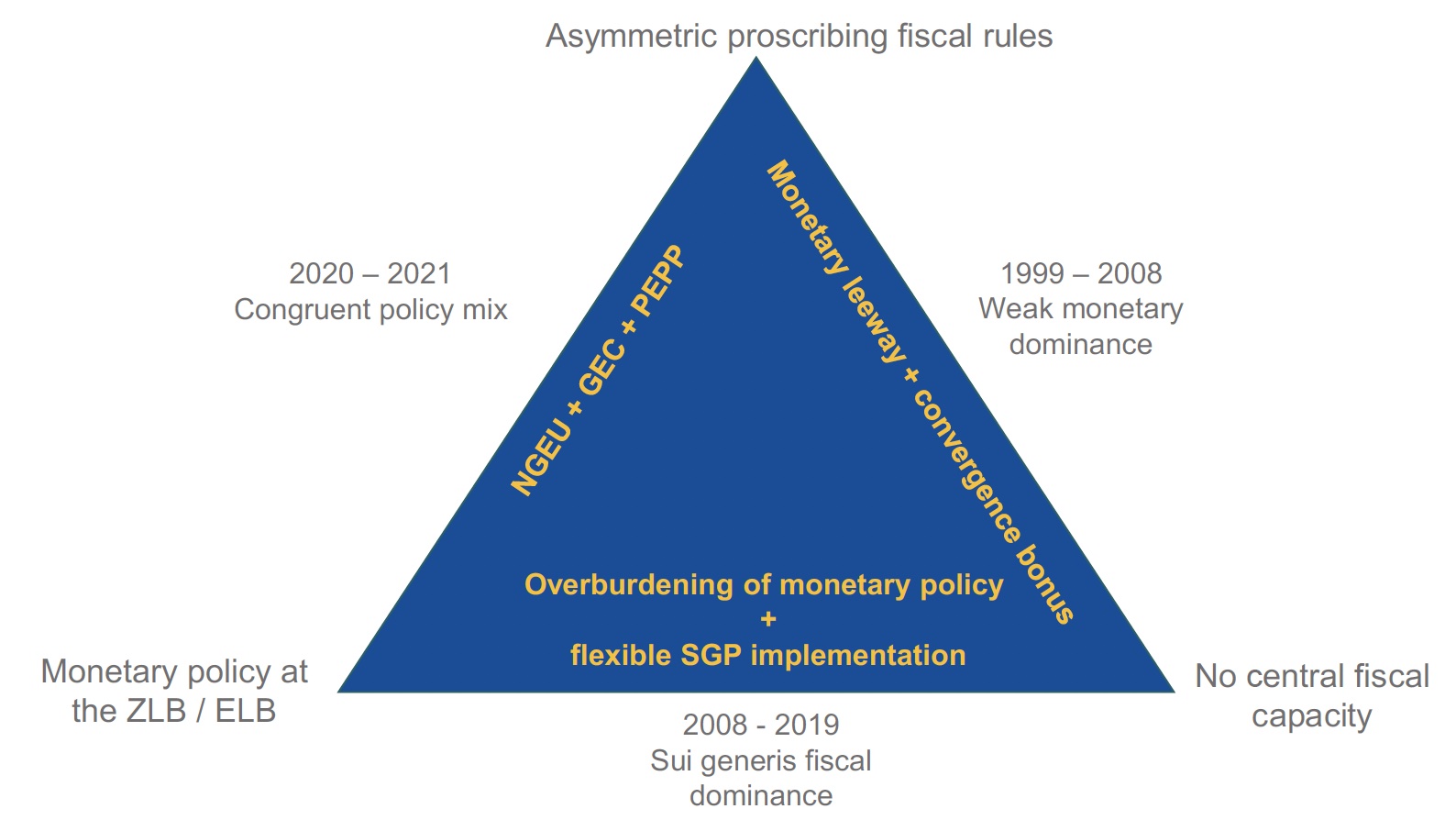

Figure 1 summarises how the policy mix trilemma has been tackled so far. After a period of weak monetary dominance

during the euro area’s first decade (1999-2007) and a short episode of

coordinated expansion at the outset of the global financial crisis, sui generis fiscal dominance

prevailed during and after the sovereign debt crisis (2011-2019). In

that period, monetary policy progressively became ‘the only game in

town’ (El-Erian 2016). During the pandemic instead, the trilemma was

resolved at the two corners characterised, respectively, by the ECB’s

attainment of the ELB and by the implementation of a central fiscal

capacity. The latter was complemented by the suspension of the SGP

adjustment requirements via the triggering of the GEC. The combination

between these initiatives, the strengthening of unconventional monetary

policies (most notably the PEPP), and the action at EU level which

showed strong solidarity among member states (SURE, NGEU), favoured the

adoption of expansionary fiscal policies even in euro area countries

without fiscal space (Messori 2021).

This exceptional policy response has entailed a more congruent policy

mix. However, given the one-off nature of NGEU and the large

accumulation of government bonds in the ECB’s balance sheet, even this

solution of the trilemma is temporary and does not ensure stable

equilibria going forward. Going forward, supplementing national fiscal

policies with a permanent central fiscal capacity would allow to attain

an adequate fiscal stance and a more balanced policy mix that would

overcome the risk of fiscal dominance. In this new policy mix with

vertical fiscal coordination, the unconventional monetary policy would

not be constrained to support the sustainability of national fiscal

policies and, thus, it would not fall again into a distortionary fiscal

dominance condition. This would ease the gradual winding down of the

government bonds accumulated in ECB’s balance sheet, when required by

monetary policy considerations. As a result, the ECB will be able to

escape the ELB as well as a distortionary and unsustainable composition

of its assets.

Figure 1 How the policy mix trilemma has been solved so far

Source: own elaboration.

The EU’s vertical fiscal coordination in practice

We have argued above that a ‘vertical’ fiscal policy coordination

between the national and the EU level will appear the appropriate way

forward, if one does not want to continue relying on the monetary arm,

with the high risk of pushing the ECB beyond its mandate. This

coordination requires building a central fiscal capacity within a

coherent ‘European budgetary system’. The EU’s current governance is

far from this solution. In response to the dramatic economic fallout of

the pandemic, vertical coordination has taken the form of setting up

NGEU, with the RRF at its core. Many observers, including the German

Finance Minister, Olaf Scholz, hailed the building of NGEU as Europe’s

Hamiltonian moment. This led to calls for making the new central fiscal

capacity a permanent feature of the EU’s post-pandemic fiscal

architecture. However, NGEU and its main programmes were explicitly

conceived as a ‘large one-off, whereas an effective central fiscal

capacity requires a permanent and stable institutional design.

The Commission has called in the past for setting up a central fiscal

capacity (European Commission 2017). What form could such capacity

take? There are, in principle, three non-mutually exclusive options:

a) creating a central stabilisation function

b) increasing the supply of EU public goods and

c) setting up conditional transfers from the EU budget.

The pros and cons of these three options are assessed in Table 1.

The first option – that is, creating a central stabilisation capacity

– would be the most rational one for the completion of the EU economic

governance, but probably also the most contentious politically. In 2018,

the Commission proposed an embryo of a stabilisation capacity based on

loans, the European Investment Stabilisation Function (EISF) (European

Commission 2018), which fell on deaf ears. The most cumbersome issue of

this option could be the ‘moral hazard’ risks characterising the

implicit contract under imperfect information between the European

fiscal supervisors and national governments. If the national governments

anticipated the support by a central fiscal instrument in case of

negative shocks or of negative cyclical phases, they would have a weaker

incentive to create national fiscal room for manoeuvre in periods of

strong growth. This is what allegedly occurred during the euro area’s

‘good times’. ...

more at VOX

© VoxEU.org

Key

Hover over the blue highlighted

text to view the acronym meaning

Hover

over these icons for more information

Comments:

No Comments for this Article