In the

debate on reforming the EU, two needs emerge: securing fiscal space for

EMU countries, and ensuring that a more proactive fiscal policy remains

sustainable even when monetary policy reverts to normal (Buti and

Messori 2022).

Debt is at

record-high levels, but the EU's future challenges involve mostly public

infrastructural investments, with a trade-off between growth and

stability. Within this context, new fiscal rules and adequate forms of

debt management ought to be established jointly (D’Amico et al. 2022a,

2022b).

In a new paper

(Amato et al. 2022), we provide a quantitative simulation-based

assessment of the impact on prices and quantities of government debt in

the euro area of the working of a European Debt Agency (EDA), placed in

the current EU debate in Amato and Saraceno (2022).

The EDA operating model

The EDA collects

liquid funds on the market by issuing finite maturity bonds. When the

EDA begins its operations, member states stop issuing bonds. The agency

provides credit to member states to finance the repayment of their

maturing bonds as well as their primary budget deficit. This credit

facility takes the form of perpetual loans, priced using a risk-adjusted

unit cost differentiated according to the member states'

creditworthiness. EDA bonds are traded, while perpetual loans are not

traded,1 thus overcoming the difficulties of creating a

market for perpetuities. An adequate initial capital endowment and a

pricing policy aimed at achieving intertemporal financial equilibrium

would allow EDA to enjoy AAA status. The perpetual loans’ instalments

charged by the EDA would be calculated (1) by considering their

fundamental risk only, and (2) by including an amortisation quota of the loan itself.

But ‘perpetual’ does not mean ‘irredeemable’, since the EDA has the

possibility to reduce its balance sheet by drawing resources from its

reserves. By progressively raising a screen between markets and member

states, the EDA would eventually filter all member states’ liquidity and

refinancing risk, transforming all the euro area debt into a safe debt.

Nevertheless, since

the EDA would differentiate the price of its loans, the cost of debt for

each member state would depend on an assessment of its fundamental

risk, leaving each member state fully accountable for its fiscal policy decisions.

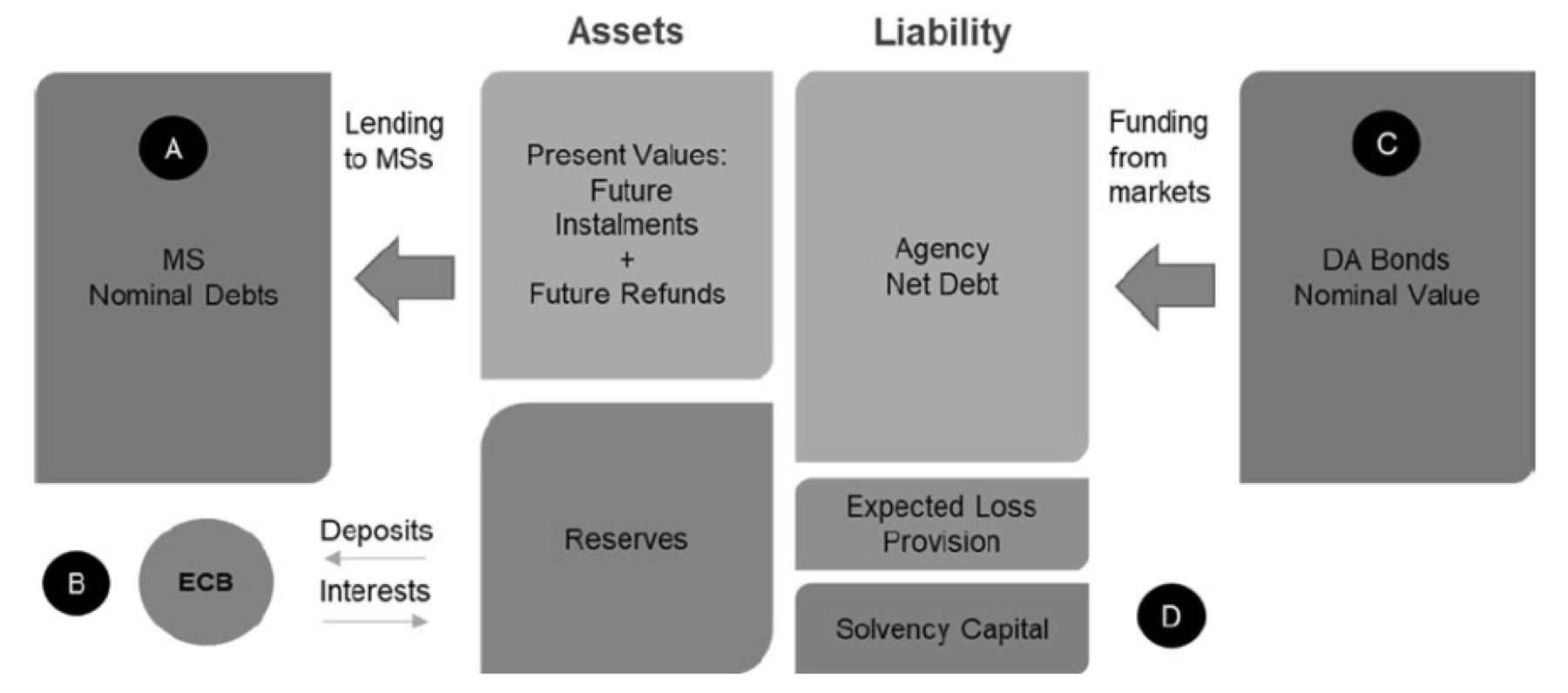

The operating model of the EDA is reflected in its balance sheet structure (see Figure 1, from Amato et al. 2021).

Figure 1 The EDA's balance sheet

A simulation exercise

We compute

historical series of the unit costs of loans with EDA for each member

state by applying the pricing framework for risky perpetual loans. We

assume that in the first period, initial capital is conferred to EDA

equal to the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) capital, reallocated

among member states according to the ESM weights. Reserve dynamics

depend then on the new inflows, annual payments on the perpetual loans,

and the remuneration of the stock. Reserves are remunerated by the ECB

at the rate paid by EDA on its bonds. Heterogeneous and independent

pricing of each country’s loans (which we label ‘idiomatic fundamental

pricing’) generates a total payment that is structurally higher than the

equilibrium payment computed by ‘pooling’ the debt of all member states

in the EDA. So, the EDA accumulates reserves in excess of the debt in

bonds that can be precisely attributed to each country. In the

simulation, the EDA absorbs all the member states’ outstanding bonds in a

decade.

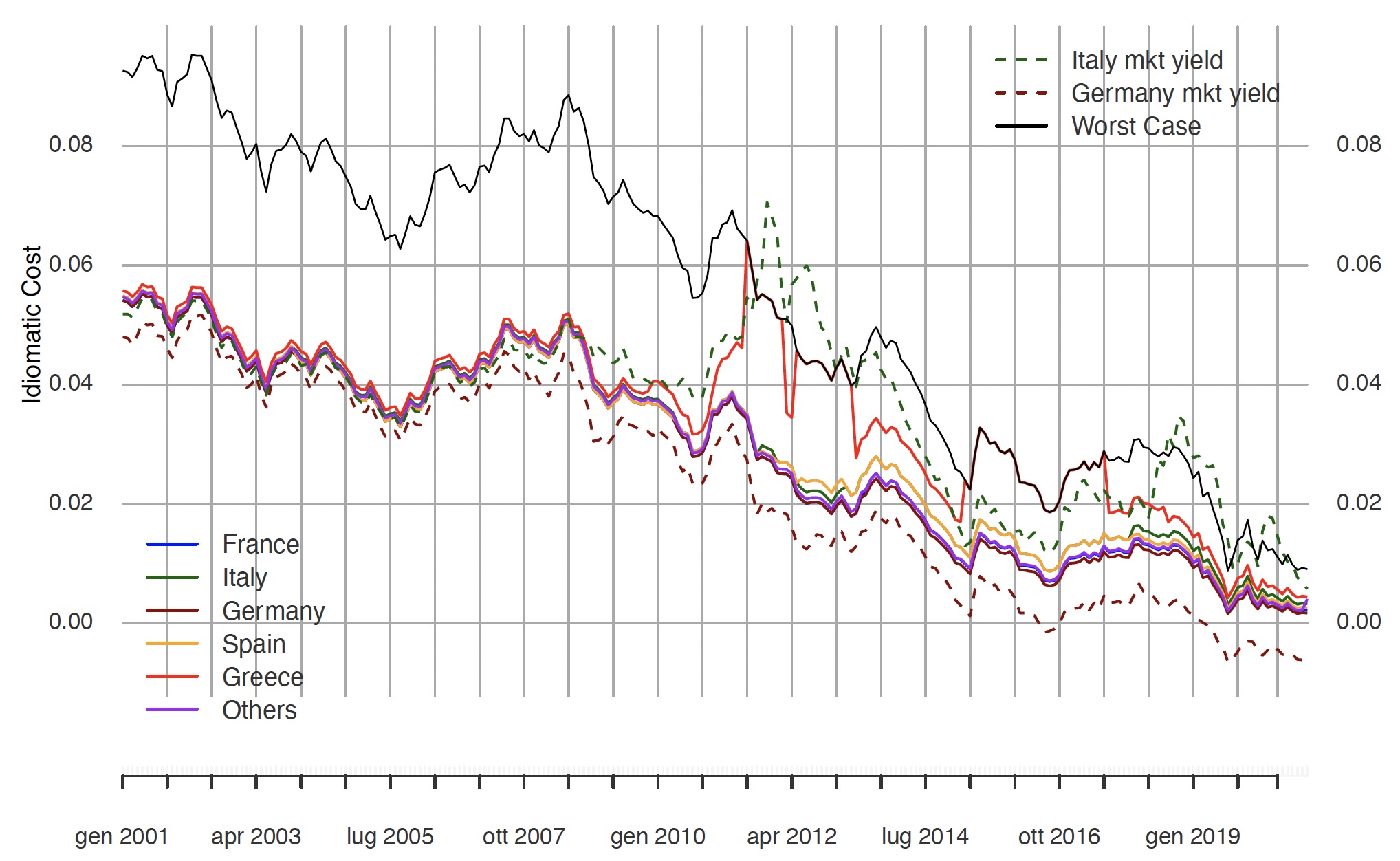

Figure 2 shows the

historical series of these costs, recalculated for each member state

based on the counterfactual hypothesis that a debt agency has been

operational since 2002, and compares them with the cost for a

hypothetical country with the credit grade ‘next to default’ and the

yields of ten-year government bonds for Germany (lower yellow dotted

line) and Italy (upper green dotted line).

Figure 2

Ten-year government bond yields (Italy and Germany) and simulated

annual costs of perpetual loans (idiomatic costs) for selected member

states and a hypothetical (worst case) next to default country

These costs are

‘risk-sensitive’, but the idiomatic pricing of risk is very different

from the pricing observed in ten-year bond yields for Germany and Italy

during the sample. Importantly, idiomatic costs do not manifest

'diverging symmetries' in favour or against a particular member state,

and neither do they feature ‘excessive fluctuations’ in their government

debt market prices.

The simulation shows

that the low reduced volatility in loans prices has beneficial

consequences for the dynamics of member states’ debt.

The reserves

accumulated by the EDA under its pricing scheme will assure (together

with an initial capital endowment) the EDA intertemporal financial

equilibrium. We measure the required risk capital in terms of the number

of forbearance years of annual instalments allowed by each member

state’s total reserves. We use this wording because in ‘bad times’ when a

member state gets close to a credit risk class close to default,

reserves accumulated with EDA can be used by the member state to access a

‘forbearance facility’. During forbearance, reserves accumulated with

the EDA are used for servicing and restructuring debt and no new loans

are issued. The procedure gives the member state time and resources to

implement the necessary fiscal stabilisation policy smoothly.

During forbearance,

the use of reserves for debt repayment increases the debt of member

states with the EDA. Interestingly, the EDA will need to issue bonds on

the market to finance only the part of the member state’s total deficit

that is not paid by using their reserves with EDA. Debt repayment allows

member states to comply with fiscal rules. Also, notice that bonds

issued by the EDA grow faster than loans with the EDA outside

forbearance, while during forbearance, the opposite happens. The

existence of the EDA will facilitate smooth compliance with debt limits,

as set by the fiscal rules. These rules could be defined naturally by

targeting the ratio of bonds issued by EDA to GDP.

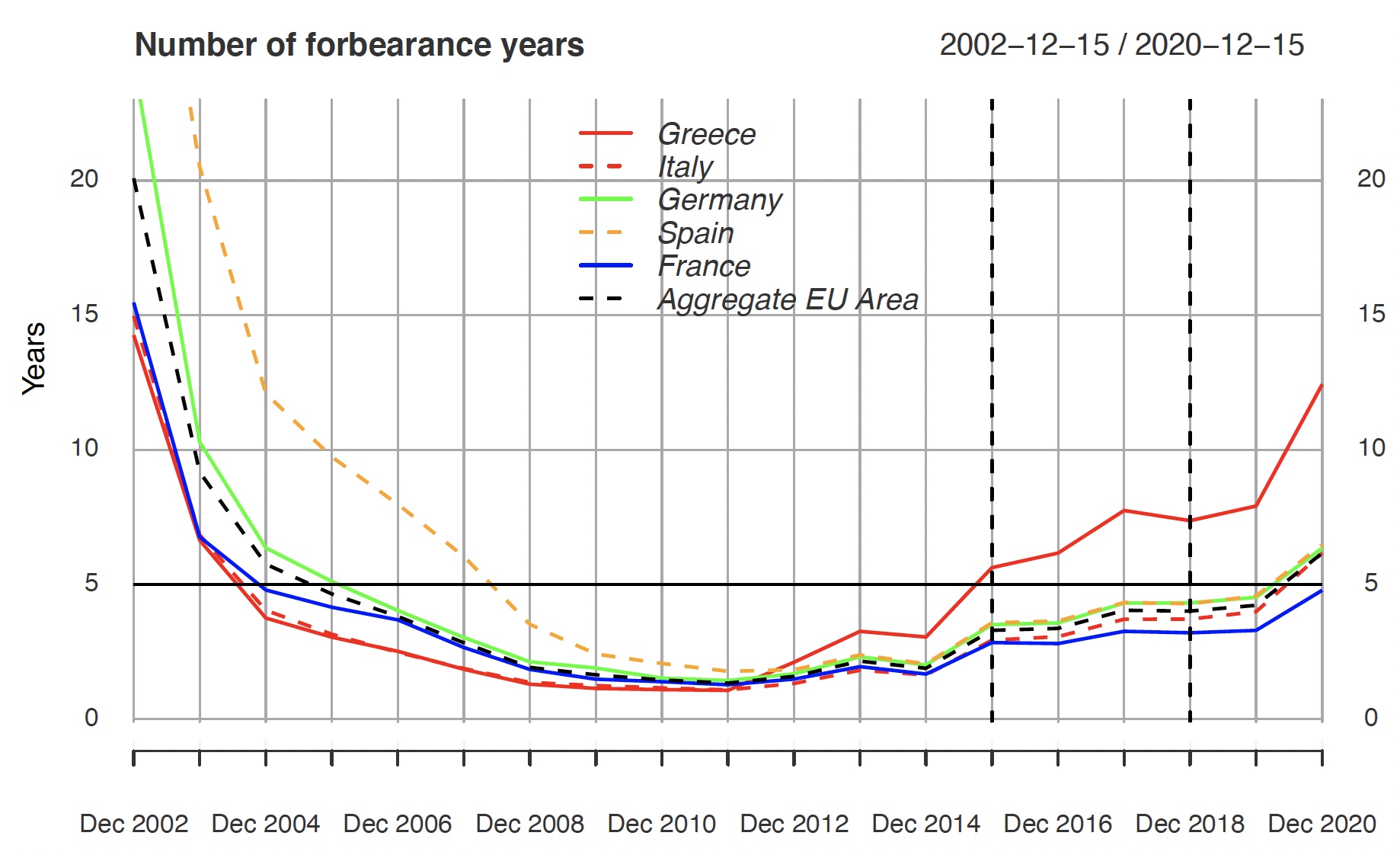

Figure 3 reports the number of forbearance years allowed by the EDA reserves.

Figure 3 Simulated EDA available capital measured in terms of payments ‘forbearance years’ for selected member states

Our counterfactual

simulations show that in the first years of EDA operations, while the

EDA is progressively acquiring member states’ maturing bonds, the

initial endowment plus the accumulated reserves give plenty of

forbearance capacity to all member states and reach a minimum just

between one and two forbearance periods, at the beginning of the fully

operational phase, which starts in 2011. Reserves then keep growing to

guarantee all member states a forbearance capacity of at least above

five years within the first ten years of the full operating period of

the EDA.

The case of the cost

for Greece is particularly interesting. This crisis was ignited by the

revelation, at the end of 2009, that Greece’s budget deficit was far

larger than the original estimates (the last revision brought it to

15.4% of GDP). Greece’s borrowing costs spiked as credit-rating agencies

downgraded the country’s sovereign debt to junk status in early 2010.

The costs that the EDA would have charged in these conditions show a

level and volatility that are not comparable with those of the observed

market prices on Greek ten-year bonds. On the occasion of the first wave

of the Greek crisis at the end of 2009, even if the available reserves

would not have allowed Greece to access forbearance, requiring

additional solvency capital to be provided externally,2 the

EDA would certainly have helped in containing contagion. However, on the

occasion of the second wave of the crisis in 2015, following the missed

payment of the IMF bailout in June 2015, a fully operational EDA would

have allowed over five years of forbearance to Greece, which would have

been very helpful to reduce the pain of fiscal stabilisation.

Conclusions: The benefits of an EDA

Establishing an EDA

would strongly reduce market instability and the cost of debt. This is

of course particularly appealing for high-debt countries and raises the

political economy issue of the feasibility of our proposal. Leandro and

Zettelmeyer (2018) provide a useful taxonomy of the characteristics that

a debt management tool should have to be politically viable and

efficient in maximising financial stability and minimising borrowing

costs. While noting that the EDA complies with all these requirements,

we argue that the EDA would benefit EMU core countries as well, and

therefore be beneficial for the single currency as a whole.

The EDA would allow a

smoother and more efficient working of financial markets and

enforcement of fiscal discipline, while also contributing to

streamlining the EMU macroeconomic policy governance. These objectives

will be achieved as EDA has the potential to:

(i) eliminate

liquidity and reprice risk, concentrating only on fundamental risk, thus

avoiding ‘bad equilibria’ (Blanchard and Pisani Ferry 2020);

(ii) establish a more efficient discipline mechanism through a fairer risk assessment;

(iii) structurally avoid mutualisation;

(iv) provide a truly

European safe asset, crucial for the economic and political positioning

of the EU in the new geopolitical context;

(v) systematically avoid juniority risk (see also Codogno and van den Noord 2019);

(vi) end the doom loop (a precondition for a full banking union and for normalising EMU bond markets);

(vii) allow the ECB to focus on its main mandate (Micossi 2021, D’Amico et al. 2022);

(viii) provide a

transparent, efficient division of labour within the commission by

separating the responsibilities for debt sustainability and debt

management and by providing a debt management institution that

facilitates the implementation of fiscal rules.

Our EDA proposal has

been guided by the three-fold need to (1) minimise borrowing costs for

member states, (2) stabilise sovereign debt markets, and (3) maximise

its acceptability in the EU political debate. This is why our proposal

is centred on the absence of debt mutualisation and continued

accountability of member states for their fiscal discipline. Good for

the EMU as a whole, the EDA would also be good for core countries. The

fact that the EDA would stabilise financial markets, help normalise

monetary policy and relieve the pressure on frugal countries (especially

Germany’s) bond markets contributes to making the proposal politically

viable for all.

References

Amato, M, E Belloni, P Falbo and L Gobbi (2021), “Europe, Public Debts, and Safe Assets: The Scope for a European Debt Agency”, Economia Politica 38(3): 823–61.

Amato, M, E Belloni, C Favero and L Gobbi(2022) “Creating a Safe Asset without Debt Mutualization: the Opportunity of a European Debt Agency”, CEPR Discussion Paper 17217

Amato, M and F

Saraceno (2022), “Squaring the Circle: How to Guarantee Fiscal Space and

Debt Sustainability with a European Debt Agency”, Baffi-Carefin Working

Papers 172 and Luiss School of Political Economy WP 1/2022.

Blanchard, O J, A Leandro and J Zettelmeyer (2021), “Redesigning EU Fiscal Rules: From Rules to Standards”, Economic Policy 36(106): 195–236.

Blanchard, O J and J Pisani-Ferry (2020), “Monetisation: Do Not Panic”, VoxEU.org, 10 April.

Buti M and M Messori (2022), "Reconciling the EU's Domestic Policy Agenda”, VoxEU.org, 11 April.

Codogno, L and P van den Noord (2019), “The Rationale for a Safe Asset and Fiscal Capacity for the Eurozone”, LEQS Paper 144.

D’Amico, L, F Giavazzi, V Guerrieri, G Lorenzoni and C-H Weymuller (2022a), “Revising the European Fiscal Framework, Part 1: Rules”, VoxEU.org, 14 January.

D’Amico, L, F Giavazzi, V Guerrieri, G Lorenzoni and C-H Weymuller (2022b), “Revising the European Fiscal Framework, Part 2: Debt Management”, VoxEU.org , 15 January.

Eichengreen B, A El-Ganainy, R Esteves and K J Mitchener (2021), In Defense of Public Debt, Oxford University Press.

Kelton, S (2020), The Deficit Myth. Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People's Economy, New York: Public Affairs.

Leandro, A and J Zettelmeyer (2018), “The Search for a Euro Area Safe Asset”, PIIE Working Paper 3.

Micossi, S (2021), “On the Selling of Sovereigns Held by the ESCB to the ESM: A Revised Proposal”, CEPS Policy Insights 2021–17.

Endnotes

1 Financing member

state debt with perpetual loans explicitly recognises the difference

between government debt and household debt (Eichengreen 2021, Kelton

2020), leveraging on the perpetual nature of public debt (Amato and

Saraceno 2022) .

2 This is one of the

reasons why, during the first phase of its existence, the EDA could be

supplemented by a temporary scheme to unburden the ECB, for example as

suggested by Micossi (2021), by conferring the Covid debt to the ESM.