Cross-border links between banks and non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) gained momentum in recent years. Banks' cross-border claims on NBFIs rose from $4.6 trillion in Q1 2015 to $7.5 trillion in Q1 2020, a faster increase than that of total cross-border claims.

Financial centres and large advanced economies play a prominent

role, as hosts of the largest and most interconnected NBFIs such as

central counterparties, hedge funds and investment funds. The size of

banks' cross-border links to NBFIs in emerging market economies has also

been on the rise, albeit from a low base. The financial market turmoil

triggered by Covid-19 revealed several vulnerabilities associated with

cross-border linkages between banks and NBFIs.1

Non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs)2

played an important role in transmitting shocks during the Great

Financial Crisis (Gorton (2010), Claessens et al (2012)). Since then,

NBFIs' assets under management have grown substantially, at even a

faster pace than banks' (FSB (2020)). In tandem, national and

international authorities have stepped up their efforts to quantify and

understand NBFIs' activities and the attendant vulnerabilities (ESRB

(2019)).

Key takeaways

- Cross-border bank claims on non-bank financial institutions

(NBFIs), such as investment funds and central counterparties, have grown

63% in the last five years to $7.5 trillion in Q1 2020.

- Financial links between banks and NBFIs are mainly denominated in

US dollars and concentrated in financial centres and large advanced

economies, but have also grown in emerging market economies.

- Vulnerabilities stemming from these growing interconnections were

highlighted during the Covid-19 market turmoil, for example in fickle

dollar funding from NBFIs and liquidity pressures from high central

counterparty margins.

Statistical data: data behind all graphs

Of particular concern are links between banks and NBFIs, which, to

echo the opening quote, are key "conjunctions" in the financial system.

Both types of institutions can engage in credit, maturity and liquidity

transformation, which could underpin the accumulation of imbalances in

normal times and pockets of stress in a downturn. Thus, links between

banks and NBFIs are behind particularly powerful transmission

mechanisms, as demonstrated most recently by the pandemic-related market

turmoil. This episode underscored that central counterparty (CCP)

margins can be procyclical and drain banks' liquidity at an inopportune

time; that money market funds (MMFs) can be fickle funding providers to

banks; and that banks' positions vis-à-vis NBFIs can contribute to their

net long currency positions. These lessons had an important

cross-border dimension.

This article is a first attempt at a global mapping of the

cross-border links between banks and NBFIs, using the BIS international

banking statistics (IBS) and focusing mainly on the residence of

counterparties.3 We use

recent enhancements to these statistics that introduced a more granular

breakdown of banks' claims and liabilities vis-à-vis non-banks, in

particular NBFIs (Avdjiev et al (2015)). Since analysis of cross-border

links between NBFIs and non-banks is currently hampered by lack of data,

we focus on the bank-NBFI nexus.

The rest of the article is organised as follows. The first section

documents the continuous growth of NBFIs as bank counterparties in

recent years. The second presents the network of cross-border links

between banks and NBFIs,4

highlighting the systemic nodes through which shocks could propagate and

the growing importance of NBFIs in emerging market economies (EMEs).

The third section assesses vulnerabilities with a particular focus on

how they materialised during the Covid-19 fallout in the first quarter

of 2020.

The growing importance of NBFIs as bank counterparties

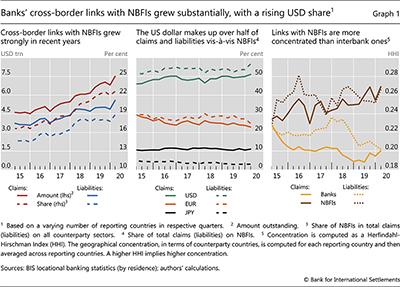

Banks' cross-border claims on, and liabilities to, NBFIs grew

strongly in recent years. The outstanding amount of cross-border claims

increased from $4.6 trillion in the first quarter of 2015 to $7.5

trillion in the first quarter of 2020, a notable rise of six percentage

points when scaled by total cross-border claims (Graph 1, left-hand panel).5

A similar increase is observed for banks' cross-border liabilities to

NBFIs, from $3.7 trillion to $5.6 trillion over the same period.6 Box A

puts the IBS in perspective by considering the overall size of NBFIs,

using data collected under the Financial Stability Board's (FSB) annual

global monitoring exercise on non-bank financial intermediation.

The US dollar dominates banks' cross-border positions with NBFIs.

More than 50% of both claims and liabilities are denominated in US

dollars (Graph 1,

centre panel), a slightly higher share than that for interbank

positions. The share of both US dollar claims and liabilities grew by 5

percentage points in the five years to Q1 2020, mostly at the expense of

euro-denominated positions. This is in line with the growing

international role of the US dollar documented in the literature (eg

Aldasoro and Ehlers (2018), Maggiori et al (2020), Erik et al (2020)).

Cross-border links between banks and NBFIs exhibit a high degree of

geographical concentration (García Luna and Hardy (2019)). Concentration

is a feature of cross-border banking more broadly (Aldasoro and Ehlers

(2019)), but it is particularly high - and rising - vis-à-vis NBFIs (Graph 1,

right-hand panel). It also varies by currency. The top three

counterparty countries respectively account for 39%, 74% and 86% of all

euro-, dollar- and yen-denominated cross-border claims on NBFIs at

end-March 2020.

Box A

The global picture of non-bank financial intermediation from FSB data

Iñaki Aldasoro, Wenqian Huang and Esti Kemp

Non-bank financial intermediation provides additional sources of

financing for households and corporates. But it can also contribute to

systemic risks through links with the banking system. In the wake of the

Great Financial Crisis, G20 leaders requested that the Financial

Stability Board (FSB) develop recommendations to strengthen the

oversight and regulation of "shadow banking". The framework developed in response includes the monitoring of non-bank

financial intermediation. Findings are reported annually to provide a

global picture of the size and growth of non-bank financial institutions

(NBFIs), as well as their links with other parts of the financial

system.

The framework developed in response includes the monitoring of non-bank

financial intermediation. Findings are reported annually to provide a

global picture of the size and growth of non-bank financial institutions

(NBFIs), as well as their links with other parts of the financial

system. Compared with the BIS international banking statistics, FSB data have a

broader coverage of NBFIs' domestic and cross-border counterparties -

including non-banks - but cover fewer jurisdictions and have no

counterparty country breakdown.

Compared with the BIS international banking statistics, FSB data have a

broader coverage of NBFIs' domestic and cross-border counterparties -

including non-banks - but cover fewer jurisdictions and have no

counterparty country breakdown.

The growth of NBFI assets exceeded that of bank assets over the past

decade, reaching 48% of total financial assets at end-2018, from 42% at

end-2008 (Graph A,

left-hand panel). As of end-2018, the combined assets of NBFIs -

consisting mostly of insurance companies, pension funds and other

financial intermediaries (OFIs) - stood at $184 trillion, versus $148 trillion for banks.

- stood at $184 trillion, versus $148 trillion for banks.

The importance of OFIs' cross-border positions relative to local

positions varies across jurisdictions. Although financial centres have

larger cross-border links, OFIs in most jurisdictions report

cross-border links representing less than 20% of their assets (Graph A, centre panel).

The bigger the role of NBFIs in the financial system of a given

jurisdiction, the bigger their share in banks' cross-border claims on

that jurisdiction. The right-hand panel of Graph A

illustrates this point by measuring the NBFIs' role with the ratio of

their financial assets under management to total financial assets within

a jurisdiction. Financial centres stand out, with relatively large NBFI

sectors that have strong cross-border links with banks (upper

right-hand corner).

© BIS - Bank for International Settlements

Key

Hover over the blue highlighted

text to view the acronym meaning

Hover

over these icons for more information

Comments:

No Comments for this Article