This year’s annual report of the European Fiscal Board provides new evidence that the EU fiscal framework does not deliver the goods. This column argues that it should be reformed without delay.

As forging consensus among EU member states takes time, the activation

of the general escape clause until end-2021 offers a window of

opportunity to build a simpler, leaner and more effective fiscal

contract. The year 2019 illustrated once again how EU member states

largely failed to build buffers in good times, those very buffers that

would have been welcome in the face of the Covid-19 shock. In 2019, and

despite sustained economic growth, the aggregate EU government deficit

has increased for the first time since 2011 while cases of

non-compliance with the preventive arm of the Stability and Growth Pact

(SGP). Like other common shocks before, the pandemic has exposed three

long-standing gaps in EMU’s architecture: (1) the lack of a genuine and

permanent central fiscal capacity; (2) adverse incentives to maintain or

scale up growth-enhancing government expenditure; (3) an intractable

set of rules and benchmarks poorly tailored to country-specific debt

reduction needs and capacities.

On 20 October 2020, the European Fiscal Board published its new annual report. The

report provides a careful assessment of 2019 and puts forward ideas on

how to strengthen the EU fiscal framework. The year 2019 marked the end

of a six-year long recovery from the financial and sovereign debt

crises. Although slowing, economic growth settled at around 1.5%, in

line with its estimated potential. Overall, last year still qualifies as

good economic times, with the level of economic activity at or above

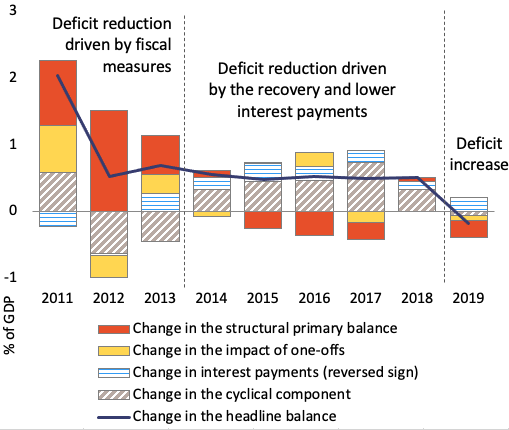

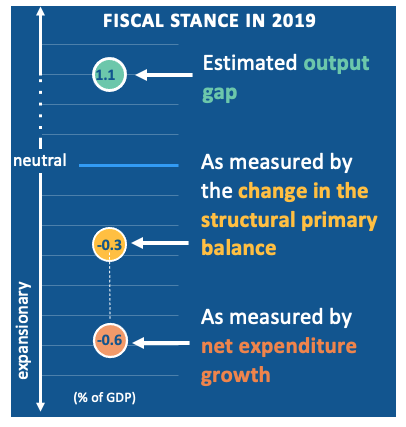

potential in the vast majority of EU countries. Despite sustained

economic growth, the aggregate fiscal position of both the euro area and

the EU weakened by around 0.25% of GDP as measured by the structural

primary budget balance (Figure 1). The deterioration of public finances

largely resulted from expenditure slippages, which more than offset

savings on interest payments.

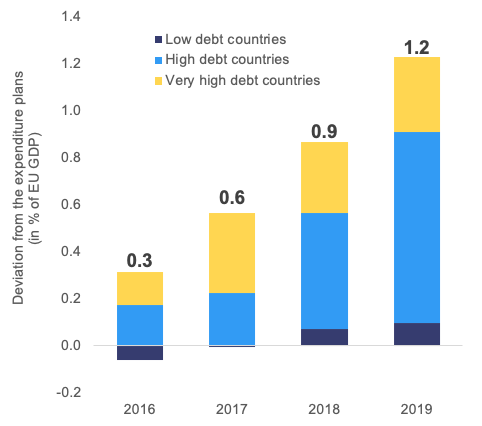

Moreover, spending

increases highlight failures to stick to budgetary plans. In the EU as a

whole, public expenditure turned out 1.2 % of GDP higher than envisaged

in governments’ medium-term budgetary plans, i.e. the Stability and

Convergence Programmes presented in spring 2018. Sizeable slippages took

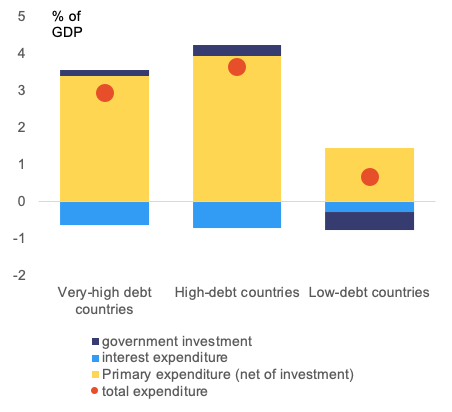

place in countries with high or very high debt levels. Furthermore, in

2014-2019 the largest part of expenditure slippages went into current

expenditure and only a very small fraction – less than one tenth – was

allocated to government investment (Figure 3).

Figure 1 Drivers of the change in the headline balance, euro area

Source: European Commission; own calculations

Figure 2 Euro area output gap and fiscal stance

Figure 3 Government expenditure slippages, EU (2016-2019)

a) By government debt level

b) By type of government expenditure

Notes:

(1) The figure shows the difference between government expenditure

outturn and spending plans in the stability and convergence programmes

over 2016-2019 as a share of GDP. (2) The classification of countries by

debt level is based on the average debt-to-GDP ratio over 2016-2019.

Very high-debt countries = above 90% of GDP (i.e. BE, ES, FR, IT, CY,

PT); High-debt countries = between 60% and 90% (i.e. DE, IE, HR, HU, NL,

AT, SI, UK); Low-debt countries = below 60% (i.e. BG, CZ, DK, EE, LV,

LT, LU, MT, PL, RO, SK, FI, SE). Share in EU GDP: low-debt group (18%),

high-debt group (44%), very high-debt group (38%).

Source: European Commission; own calculations

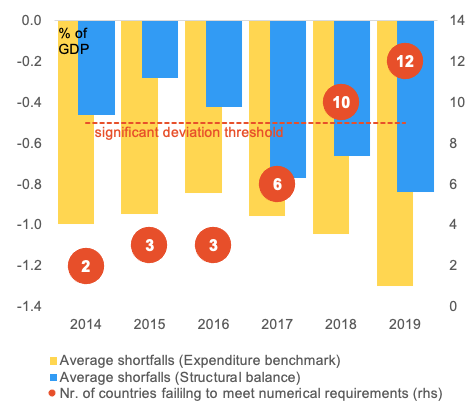

A record number of non-compliant cases with no follow up

In its final

assessment, the Commission found that ten countries fell short of the

SGP’s required fiscal adjustments by a large margin (i.e. Belgium,

Estonia, Spain, France, Hungary, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Slovakia,

and the UK) while three failed to reduce their high debt levels at the

required pace (Belgium, France, and Spain). In early 2020, an excessive

deficit procedure (EDP) was opened only for Romania due to a planned

breach of the 3% of GDP deficit reference value in 2019. The number of

countries significantly deviating from the rules in 2019 was the highest

since the six and two-pack legislative reforms of 2011-2013. Similarly,

the size of the deviations was the highest since 2014 (Figure 4). Once

again, many governments failed to take advantage of good economic

conditions to build buffers.

Figure 4 Deviations from fiscal requirements (2014-2019)

Notes:

(1) A country is considered to fall short of its requirement under the

preventive arm of the SGP when both the established compliance

indicators (i.e. the structural balance and the expenditure benchmark)

show a deviation from the MTO or from the adjustment towards it. (2) The

chart excludes countries in EDP.

Source: European Commission; own calculations

The spread of the

COVID-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020 radically changed conditions.

Triggered by the sanitary measures aimed at containing the spread of the

virus, the deepest recession since the Great Depression was met by

massive fiscal expansions in all countries. The economic and social

impact of the pandemic fully justified the activation of the general

escape clause of the SGP, allowing governments to respond to the crisis

as they saw fit. Although the clause does not apply to 2019, the

Commission and the Council agreed that the exceptional impact of the

pandemic in 2020 did not warrant any action related to widespread

non-compliance the year before. The conditions under which the clause

would be de-activated should nevertheless be clarified soon enough to

keep fiscal expectations well anchored.

Reforming the pact

Before the COVID-19

pandemic wreaked havoc on public finances in the EU, the effectiveness

of the fiscal rules had already been put into question. In the

relatively favourable years up to and including 2019, deficiencies in

the rules became evident: complications and ambiguities; pro-cyclical

fiscal policies; and declining government investment. The EFB (2019)

provided an extensive overview of these weaknesses. Our review of the

most recent experience confirms this assessment, not least with respect

to the inability to build fiscal buffers in good times.

The Commission’s

economic governance review of 5 February 2020 launched a debate on how

to improve the SGP. With the aggregate euro area and EU deficit now

expected to surge from just 0.6% of GDP in 2019 to around 8.5% in 2020

and debt ratios at historic highs, the Commission’s review and

consultation will take place in a completely new context with

potentially far-reaching implications. From the current perspective, the

long-standing deficiencies seem even more obvious: non-observable

short-term policy indicators such as the structural balance are

surrounded by even higher uncertainty; the responsibility for sustaining

investment has temporarily been assumed by the NGEU, but will require

national follow-up; fiscal stabilisation subject to sustainability

constraints must be reassessed to leave more room to support demand in

the low interest-rate environment....

more at Vox

© VoxEU.org

Key

Hover over the blue highlighted

text to view the acronym meaning

Hover

over these icons for more information

Comments:

No Comments for this Article