Completing the EU’s banking union might be the only way to avoid the dreaded “doom loop.”

Europe faces a predicament. Even as it struggles to contain the

Covid-19 pandemic, it’s setting itself up for another crisis — this one

financial. To ensure the viability of the common currency at the heart

of the European project, the EU’s leaders will have to cooperate in ways

they’ve so far resisted.

Adopting the single currency has yielded great benefits, from

frictionless trade to improved global competitiveness. But the euro

also obliged member states to relinquish the independent monetary

policies that can help backstop national debts and financial systems.

One result is that distress at banks presents a heightened threat to

individual governments’ finances, and vice versa — the so-called “doom

loop” that played out in spectacular fashion during the early 2010s,

when the euro area nearly broke apart.

In 2012, European leaders agreed

on what should have been a big part of the solution. They envisaged a

full banking union, in which governments would take joint responsibility

for supervising financial institutions — and, most important, for

dismantling or recapitalizing banks when necessary, and for making

depositors whole. Progress has been excruciatingly slow. Although the

European Central Bank now oversees the region’s largest banks,

individual governments still bear the cost of rescues, as bailouts in Italy and Germany have demonstrated. Mutual deposit insurance remains no more than a proposal.

The pandemic has aggravated the problem, with governments

taking on ever more debt in their efforts to provide economic relief.

The International Monetary Fund estimates

that general government debt in the euro area will exceed 98% of gross

domestic product by the end of 2021, up from 84% at the end of 2019.

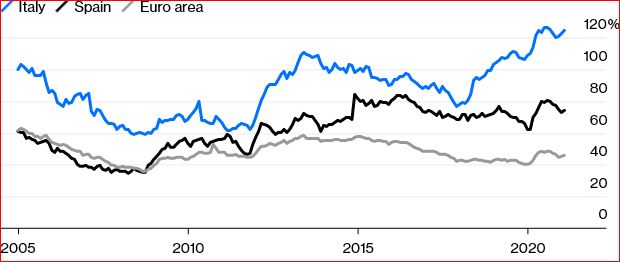

Worse, individual countries’ obligations are accumulating

on the balance sheets of their banks. At the end of February, Italian

banks’ holdings of Italian government debt amounted to 124% of their

capital and loss reserves, rendering them extremely vulnerable in the

event of fiscal distress.

Too Close to Home

Banks' holdings of home government debt have surged amid the pandemic*

Source: European Central Bank

Aside from the financial risks they present, these sovereign

exposures make banking union harder to achieve politically. Northern

countries such as Germany, for example, don’t want to sign on to mutual

deposit insurance if it means subsidizing Italian banks’ excessive

holdings of Italian public debt. Governments of heavily indebted

countries, for their part, worry that restrictions on banks’ holdings

could render them unable to borrow when they have to.

There’s a way forward. To nudge banks toward diversification,

the ECB could designate a “safe portfolio” of government debt,

corresponding to member states’ shares of the region’s GDP (an idea

originally proposed by German Finance Minister Olaf Scholz, and elaborated

by Luis Garicano, an economist and member of the European Parliament).

Any divergence would entail an increase in capital requirements. This

would address northern countries’ concerns by giving banks an incentive

to reduce home-government exposures. At the same time, it would moderate

the pressure that would otherwise be imposed on heavily indebted

governments: The decrease in Italian banks’ holdings of their

government’s debt would be at least partially offset by increases in

other banks’ holdings....

more at Bloomberg

© Bloomberg

Key

Hover over the blue highlighted

text to view the acronym meaning

Hover

over these icons for more information

Comments:

No Comments for this Article