The level of interest of European citizens in the European Union is increasing, but still lags behind EU economic and policy integration.

There

is a persistent narrative about the European Union according to which

progressive European unification is an endeavour pursued by elites

against the wishes, or at least without the support, of a majority of

the population. The ongoing Conference on the Future of Europe,

aimed at increasing popular debate about European integration, is the

latest attempt to get to grips with this narrative. The implications of

the narrative, combined with another about the insufficient public

governance of EU economic integration, are that the European

construction lacks proper democratic foundations and that it is

intrinsically fragile in the face of shocks.

Of course, supporters of European

integration stress that, over the decades, the EU has not only survived

and grown but has also confirmed founding father Jean Monnet’s prophecy

that Europe would be built on the back of solutions to its recurrent

crises. This is a strong argument, but not strong enough, because

European integration has become more and more pervasive and the question

of whether it has solid democratic foundations remains critical.

Low turnout in European elections is often

cited as proof of citizens’ limited support of, or even interest in,

the European project. European election turnout is typically lower than

in national elections, notwithstanding the increase of eight percentage

points in the 2019 European election, to 50.7%. But this quantitative

evidence does not seem strong enough to reach convincing conclusions

about public engagement with the EU. Complementary measures of European

integration and the interest of European citizens in European affairs

can give quantitative evidence to confirm, or disprove, these narratives

(details of our research on this can be found here and here).

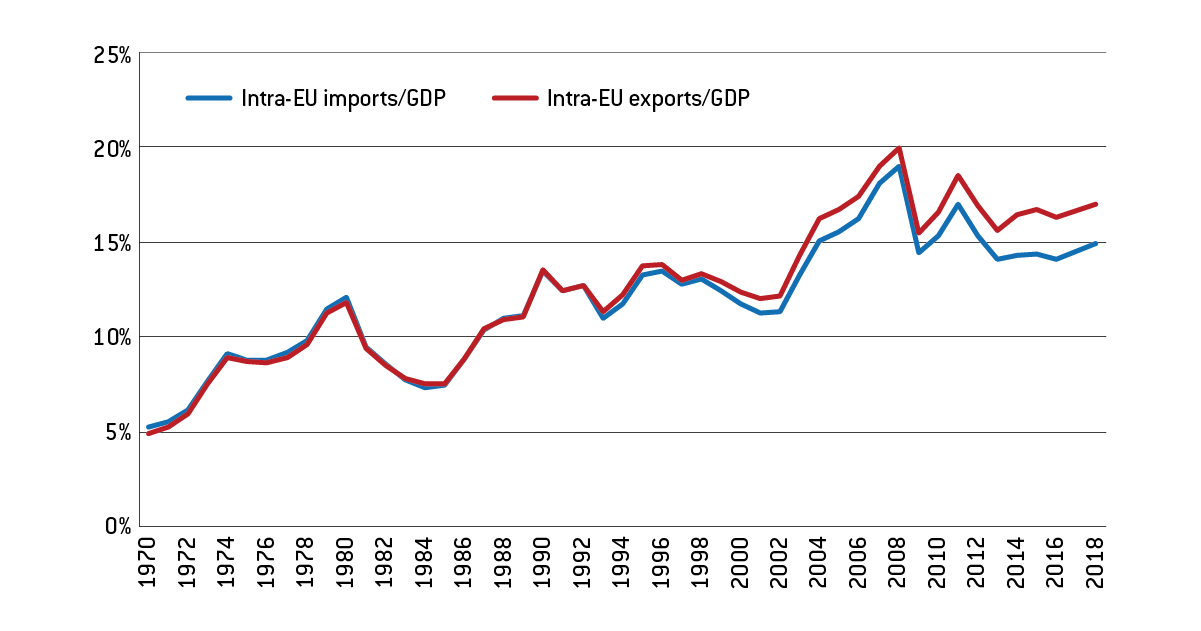

Economic integration is the easiest

variable to measure. Trade integration, measured as intra-European trade

relative to GDP, can be tracked back over a half a century (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Intra-European Union trade as a percentage of EU GDP (1970-2018)

Source: Figure 3 in Papadia and Cadamuro (2020).

Figure 1 shows an increase in

intra-European trade relative to GDP from 1970 up to the Great

Recession, but no clear trend since. Over the entire period, trade as a

share of GDP increased from 5% to 15% or slightly more, thus increasing

by a factor of about three. Another measure of economic integration,

financial integration (measured by cross border capital flows relative

to total financial size), can only be measured over the last two decades

and increased over this period by about 60%.

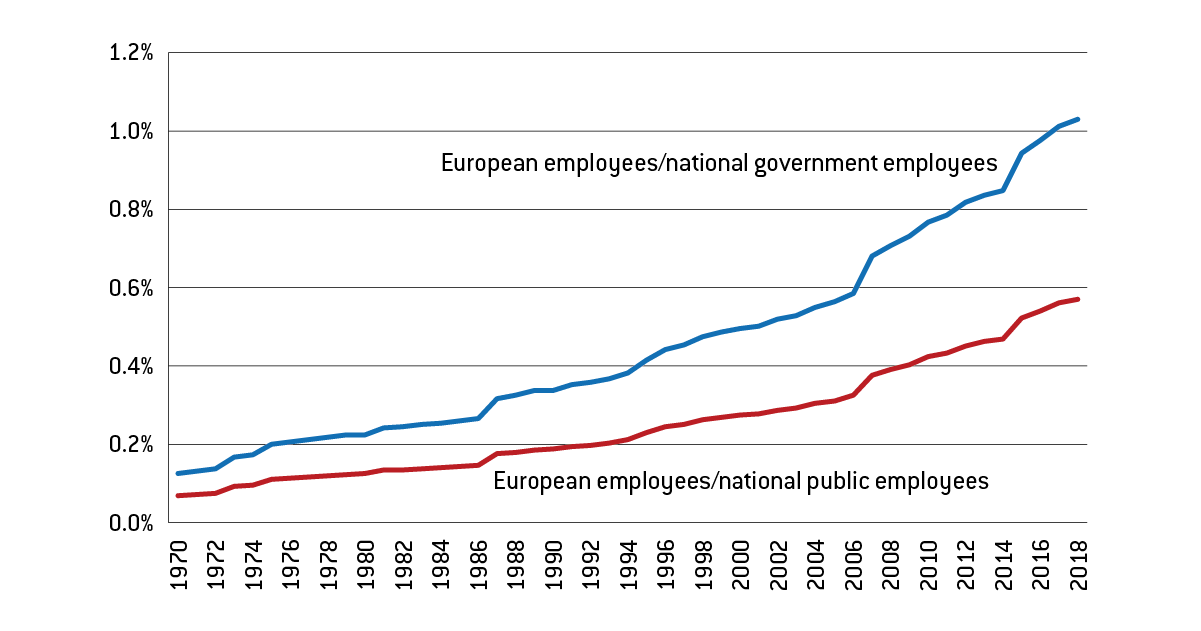

Another integration measure is policy

integration, or the amount of policy and administrative action taking

place at European rather than national level. This is harder to measure

than economic integration, but the number of European public employees

relative to the aggregate number of national employees can be used as a

proxy, assuming that one public employee at European level carries out

the same amount of policy and administrative work as a national public

employee.

Figure 2 shows that the number of

employees in European public organisations remains a very small fraction

of the number of employees in national public organisations, but in

percentage terms this fraction has increased by a factor of about eight,

a significant increase in relative importance.

Figure 2: European public employees as a percentage of total national public employees (1970-2018)

Source: Figure 6 in Papadia and Cadamuro (2020).

Meanwhile, three proxies can be used to measure changes in the level of interest of European citizens in European affairs:

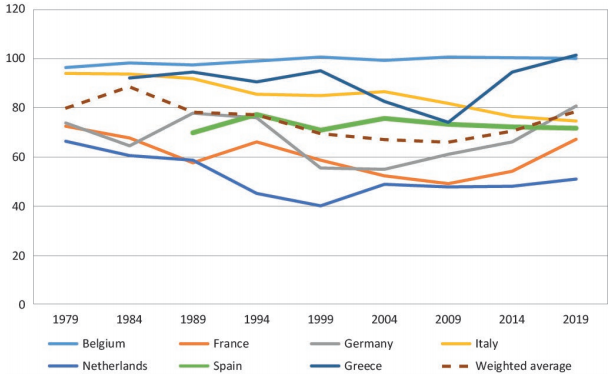

- Turnout at European Parliament elections relative to national elections (Figure 3);

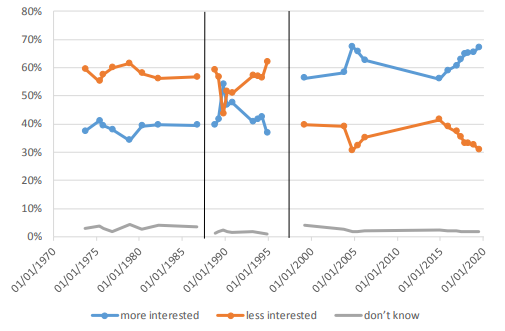

- Eurobarometer surveys on interest in European politics/attachment to Europe relative to one’s country (Figure 4);

- The presence of European news relative to total news in three elite newspapers (Figure 5).

Figure 3: European Parliament elections turnout relative to turnout in national elections (1979-2019)

Source: Figure 1 in Papadia et al (2021).

Figure 3 shows three phenomena:

- With the exception of Belgium, which has compulsory voting and

synchronises its elections calendar with European elections, and Greece

in the most two recent observations, turnout is lower in European

elections than in national elections, in some cases much lower. On

average for the selected countries, at the end of the period

participation in European elections was close to 80% of participation in

national elections.

- Relative turnout per country is quite different, with the

Netherlands and France on the low side and Belgium, Greece, Italy and

Germany on the high side.

- Average relative turnout tended to fall over the first two or three

decades in which direct European Parliament elections took place, and

then stabilised, before increasing more recently.

The usual interpretation that a low level

of European election turnout is a sign of voter disinterest in the EU

itself needs qualification. While turnout in European elections is

certainly below most national elections in Europe, it has often been in

the range of, for example, US mid-term elections to the House of Representatives. European election turnout has even been above turnout in Swiss federal elections in all years but 2009 and 2014.

The latter case could be explained by Swiss citizens attaching

relatively less importance to federal elections because they frequently

vote in referendums. In a semi-parallel to the Swiss situation, voters

may perceive European elections as less important because EU decisions

need to go through the Council of the EU as well as the European

Parliament.

Figure 4: Interest in European politics/attachment to Europe (1973-2019), Eurobarometer surveys

Source: Figure 3 in Papadia et al (2021).

An overall reading of Figure 4 shows no

trend change in the level of public interest in European politics

between 1975 and 1994, and a significant, yet irregular, increase in

attachment to Europe only over the last two decades, coinciding, not

surprisingly, with the introduction of the euro and EU enlargement.

The vertical lines represent changes in

the phrasing of the question in Eurobarometer surveys: in the first two

panels the question relates to ‘interest in EU politics’, but in the

second panel an added additional option was available as an answer (‘to

some extent’, that we split between ‘more interested’ and less

interested, for the ease of reading); in the final panel the question

relates to ‘attachment to Europe’.

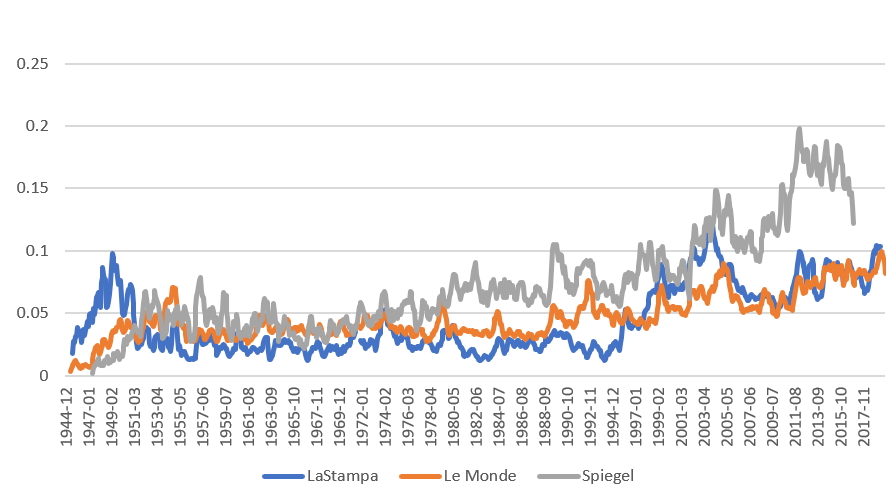

Figure 5: Frequency of European news relative to total news, selected European newspapers (1945-2018)

Source: Figure 5 in Papadia et al (2021). For details on the construction of the series see Bergamini and Mourlon-Druol (2021). For details on the individual newspapers, see blog posts on Le Monde, Die Zeit and Der Spiegel, and La Stampa.

Figure 5 shows European news as a share of total news in three selected newspapers (Le Monde, La Stampa, Der Spiegel).

These are elite newspapers, but still indicative of more general public

opinion changes at national level. Overall, there has been a

significant increase in the frequency of European news since the 1940s

in all three newspapers:

- Le Monde included about two articles about Europe out of

100 in the 1940s; the percentage increased about fourfold to around 8%

in the 2010s;

- The frequency of European news in Der Spiegel increased by a factor of around six, from about 2% to more than 12%;

- The frequency of European articles in La Stampa increased about fivefold over the period.

Overall, there has been much variability

in the level of European news, with some distinct peaks and troughs,

which in most cases can be connected with European events, but there is evidence of a more sustained level in recent decades, broadly coinciding with the introduction of the euro.

Reaching clear conclusions from all this

evidence is not straightforward. However, overall, the picture is of

policy and administrative integration at European level growing even

beyond economic integration. The fear that an integrated private sector

has outstripped the ability of the public sector to govern the economy

is not confirmed by our data. However, the interest of citizens in

Europe, while growing, especially since the introduction of the euro,

has not kept pace with economic and policy integration. We cannot,

therefore, discard the view that European integration still has a

technocratic character and European citizens are still not sufficiently

engaged. It is true that interest in European affairs (as identified in

Eurobarometer surveys and the relative turnout in European Parliament

elections) has grown to a level of about three quarters of interest in

national affairs, but arguably it remains insufficient given the levels

of economic and policy integration, while the increase in the frequency

of European news relative to total news has not kept track with the

increase in economic and policy integration.

The new Conference on the Future of Europe has the goal of “giving citizens a greater role in shaping EU policies and ambitions”. This goal is fully justified. Time will tell if, this time, it will be achieved.

Recommended citation:

Bergamini, E., E. Mourlon-Druol, F. Papadia and G. Porcaro (2021) ‘Do citizens care about Europe? More than they used to’, Bruegel Blog, 26 April

Bruegel

© Bruegel

Key

Hover over the blue highlighted

text to view the acronym meaning

Hover

over these icons for more information

Comments:

No Comments for this Article