Proponents and opponents of the Swiss-EU institutional framework agreement have different takes on the impact of a success or failure of the agreement.

Switzerland’s

bilateral relationship with the European Union has been the subject of

intense debate for years. In 2014, the two sides began negotiations on

the terms of an institutional framework agreement that would

institutionalise their bilateral relationship. On 26 May, the Swiss

government announced that it was withdrawing from these negotiations and

would not sign the agreement.

The EU has repeated that, in the event of

failure, it will no longer conclude any new market access agreements

with Switzerland and will not update any existing agreements. This would

cause problems ranging from new certification hurdles for the medical sector and the mechanical engineering industry

to a reduction in electricity security and severe limitation of

opportunities for Swiss researchers to participate in Horizon Europe.

*The EU-Switzerland institutional framework agreement

The ‘InstA’ is intended to institutionalise the relationship between

Switzerland and the EU more strongly, in particular by dynamically

updating the current bilateral market access agreements and providing a

dispute settlement mechanism for any conflicts over the application and

interpretation of the bilateral agreements. The objective of the

institutional framework agreement is to consolidate and further develop

bilateral relations between Switzerland and the EU. In addition to Swiss

fundamental opposition on sovereignty grounds, the agreement ultimately

failed because three outstanding issues (relating to wage protection,

the EU citizenship directive, and state aid rules) could not be

resolved.

Erosion of the bilateral relationship or creeping EU accession?

Switzerland is a direct democracy, so any

international treaty must be ratified through a popular referendum. But

the Swiss public is split on the InstA issue. This is not surprising as

the opinions of Swiss voters differ widely on the opportunities and

risks of concluding the institutional framework agreement and its

failure. The only thing both sides agree on is that the question “framework agreement, yes or no” is of great relevance for the future bilateral relationship.

InstA supporters fear an erosion of the

bilateral path and a gradual exclusion of Switzerland from the European

single market and other benefits of the European integration project.

The opposing side fears that the conclusion of the institutional

framework agreement will weaken Switzerland’s national sovereignty and

that the agreement could be the first step toward ‘creeping EU

accession’.

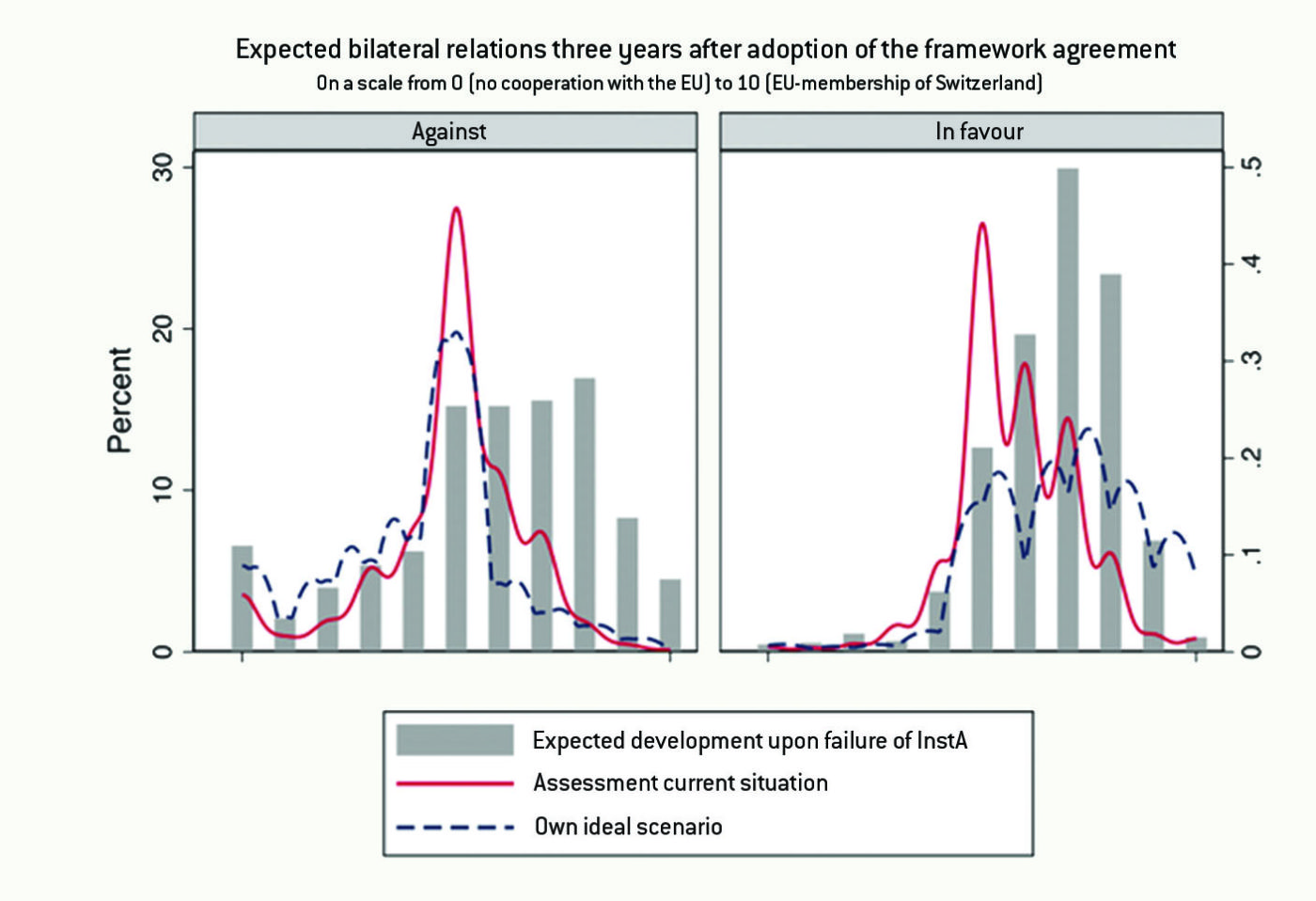

Expectations of how the bilateral

relationship will develop after the signing or failure of the

institutional framework agreement vary widely, as a survey of 1492

respondents conducted in September 2020 by a team of researchers led by Stefanie Walter

at the University of Zurich shows. Respondents were asked to assess the

medium-term development of bilateral relations on a scale of 0 (no

cooperation) to 10 (Switzerland joining the EU). Figures 1 and 2 show

the expectations of both sides about the development of the

EU-Switzerland relationship in these two scenarios: acceptance (Figure

1) and failure (Figure 2) of the institutional framework agreement.

The figures show that respondents who

would definitely or rather vote in favour of the institutional framework

agreement rated the impact on a cooperative relationship with the EU as

stronger than respondents who would vote against it: on average a value

of 6.7, compared to a value of 5.8 on the side of the opponents.

Interestingly, both sides expected similar

‘integration effects’ from the institutional framework agreement. Both

groups saw the institutional framework agreement as a step towards

stronger cooperation with the EU in the order of about one point on the 0

to 10 scale. However, since both groups also assessed current bilateral

relations differently (red line in the charts), the proponents expected

the institutional framework agreement to lead to stronger cooperation

with the EU overall than the opponents.

This movement toward more cooperation

corresponds to the preferences of respondents who were in favour of the

institutional framework agreement (dark blue dashed line), as they

generally saw a somewhat closer relationship between Switzerland and the

EU – but not EU accession – as the ideal scenario. For the opposing

side, however, this was not the case: for these voters, the status quo

of Swiss-EU bilateral relations with its dense web of bilateral

treaties strongly corresponded to their ideal. A change toward more

cooperation as a result of the institutional framework agreement would

therefore shift the status quo in a direction they would not favour.

Figure 1: Bilateral relations: ideal scenario, status quo and expected development on adoption of the institutional framework agreement, September 2020.

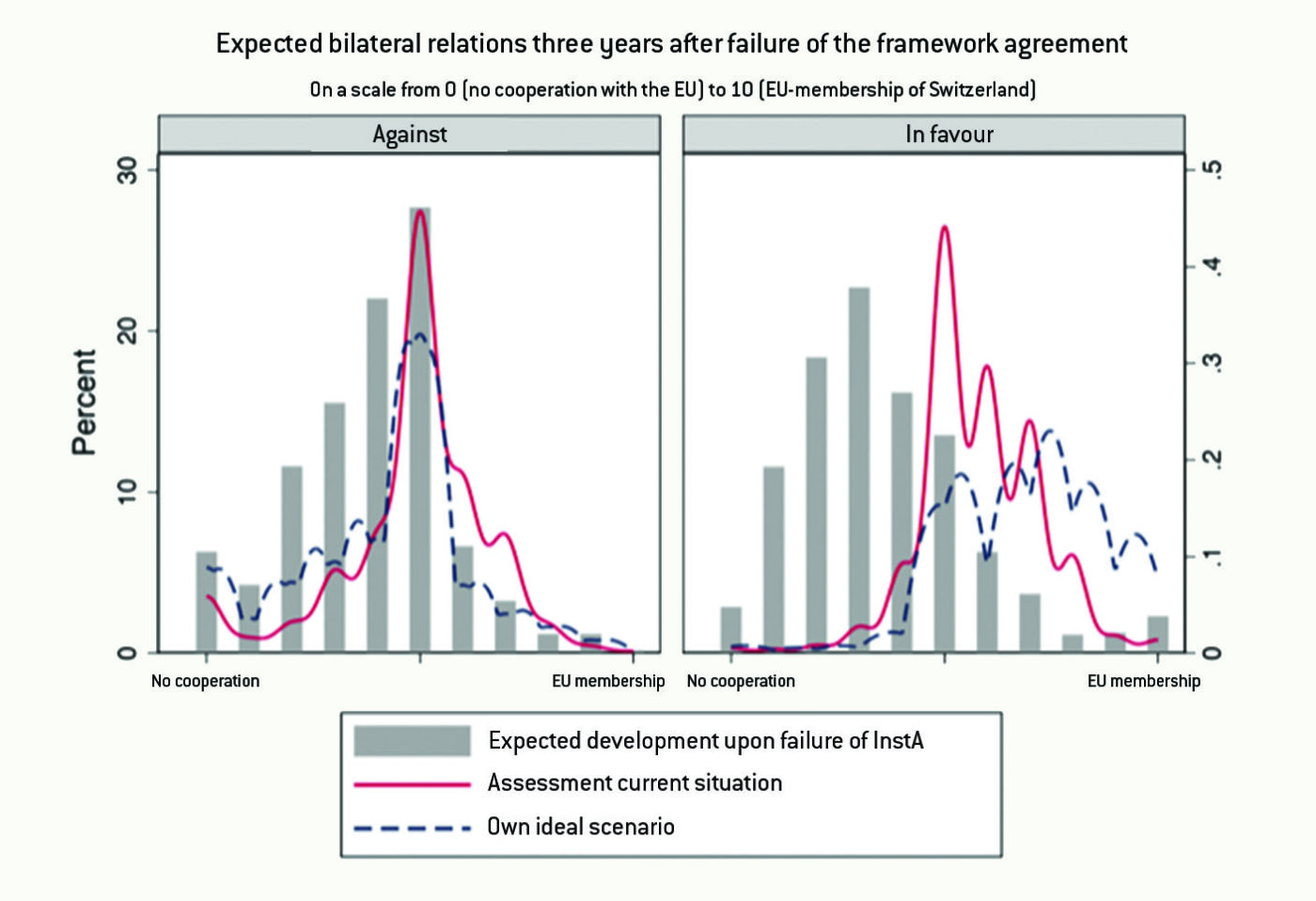

Opinions on failure diverge sharply

Opinions on the consequences of a failure

of the institutional framework agreement, on the other hand, diverged

more sharply. Although both sides expected a move toward a

less-cooperative relationship, the supporters of the agreement feared a

much more significant deterioration in bilateral relations overall.

Taking the assessment of the current state

as a reference point, supporters expected a reduction in cooperation to

the tune of 2.2 points, while opponents expected a reduction of only

0.9 points. At the same time, the mean value of bilateral relations

expected in case of failure was significantly closer to the opponents’

ideal scenario than in case of acceptance of the agreement (distance of

0.3 points in case of failure and 1.7 points in case of acceptance).

For the supporters of the agreement, on

the other hand, a failure would mean a significant deterioration in

Swiss-EU relations compared to their ideal scenario (distance of 3.4

points). In contrast, an acceptance of the agreement comes close to

their ideal scenario with a distance of 0.3 points.

Figure 2: Bilateral relations: ideal scenario, status quo and expected development in the event of a failure of the institutional framework agreement, September 2020

What are the opportunities and risks of a Plan B?

Given the differences in wishes and

expectations on both sides, it was not surprising that both sides also

assessed the risks of a failure of the institutional framework agreement

differently.

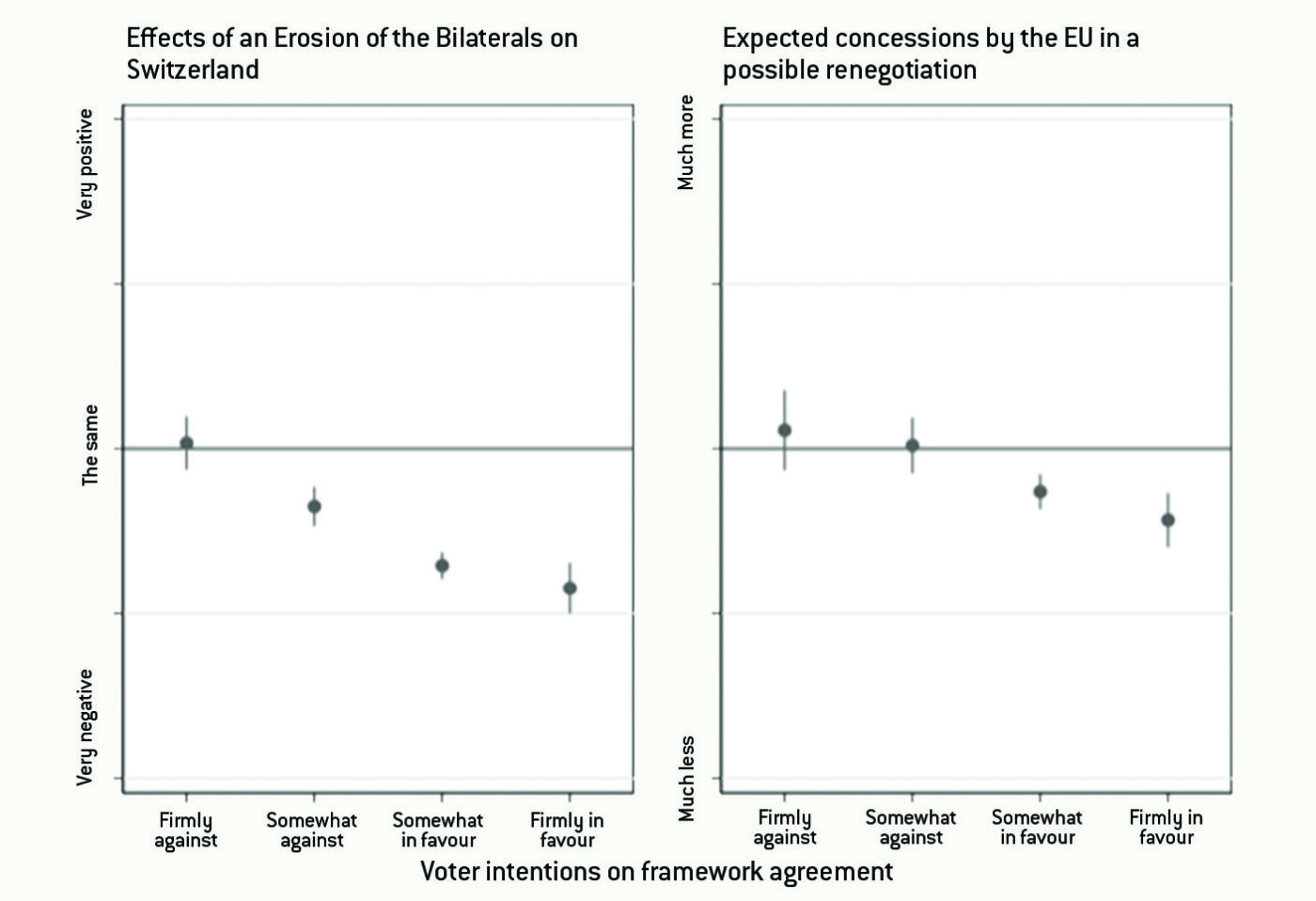

Based on data from February 2021, Figure 3

shows that respondents who would certainly vote against the agreement

thought that an erosion of the bilateral treaties would have no impact

on Switzerland. Neither did they not see any risks in the case of new

negotiations on an institutional framework agreement, but expected the

EU to be about as willing to compromise as in the current draft. That

said, they also did not see much chance that the EU would be more

willing to compromise.

All other groups, on the other hand,

feared that Switzerland would be negatively impacted if the EU indeed

refuses to update existing agreements and does not conclude any new

agreements with Switzerland until an institutional framework agreement

is signed. In addition, respondents who would vote for the institutional

framework agreement expected that the EU would be less willing to

compromise in the event of a failure and a subsequent second attempt at

negotiations, than with the current draft.

Recollections of the failed German-Swiss

state treaty on the settlement of the aircraft noise dispute suggest

that this is certainly a possible scenario. That treaty was rejected by

the Swiss parliament in 2003 as not sufficiently favourable to

Switzerland. Germany subsequently imposed unilateral restrictions on

flight movements, so that Switzerland ended up in a significantly worse

situation than envisaged in the rejected state treaty.

Figure 3: Individual expectations

about the consequences of failure and renegotiation of the institutional

framework agreement, February 2021

Such strong differences in individual

expectations about the consequences of non-cooperative decisions in

international relations are not unusual.

Various studies document similar

differences, for example, among British respondents before the 2016

Brexit referendum, when the pro-Brexit side considered the risks of Brexit to be significantly lower than the opposing side and were convinced, for example, that the UK would not lose barrier-free access to the European single market even after a Brexit. Similarly, in the 2015 Greek bailout referendum, a majority of ‘No’ voters were convinced that a no vote would force the other euro states to make greater concessions

in negotiations on the terms of a bailout package. However, these

expectations about the willingness of the negotiating partner to make

far-reaching concessions proved to be too optimistic in both cases.

The negotiating strategy: Brexit as a model?

The parallels to Brexit are not merely

theoretical; the Brexit process has strongly shaped the political

process in Switzerland around the institutional framework agreement.

Negotiations were conducted in the shadow of Brexit, the debate on the

institutional framework agreement repeatedly referred to Brexit, and the Brexit process itself helped to influence the voting intentions of the Swiss electorate on European policy.

Against this background, it is not surprising that the question of the

extent to which the British negotiation strategy should be a model for

Switzerland has been the subject of heated debate.

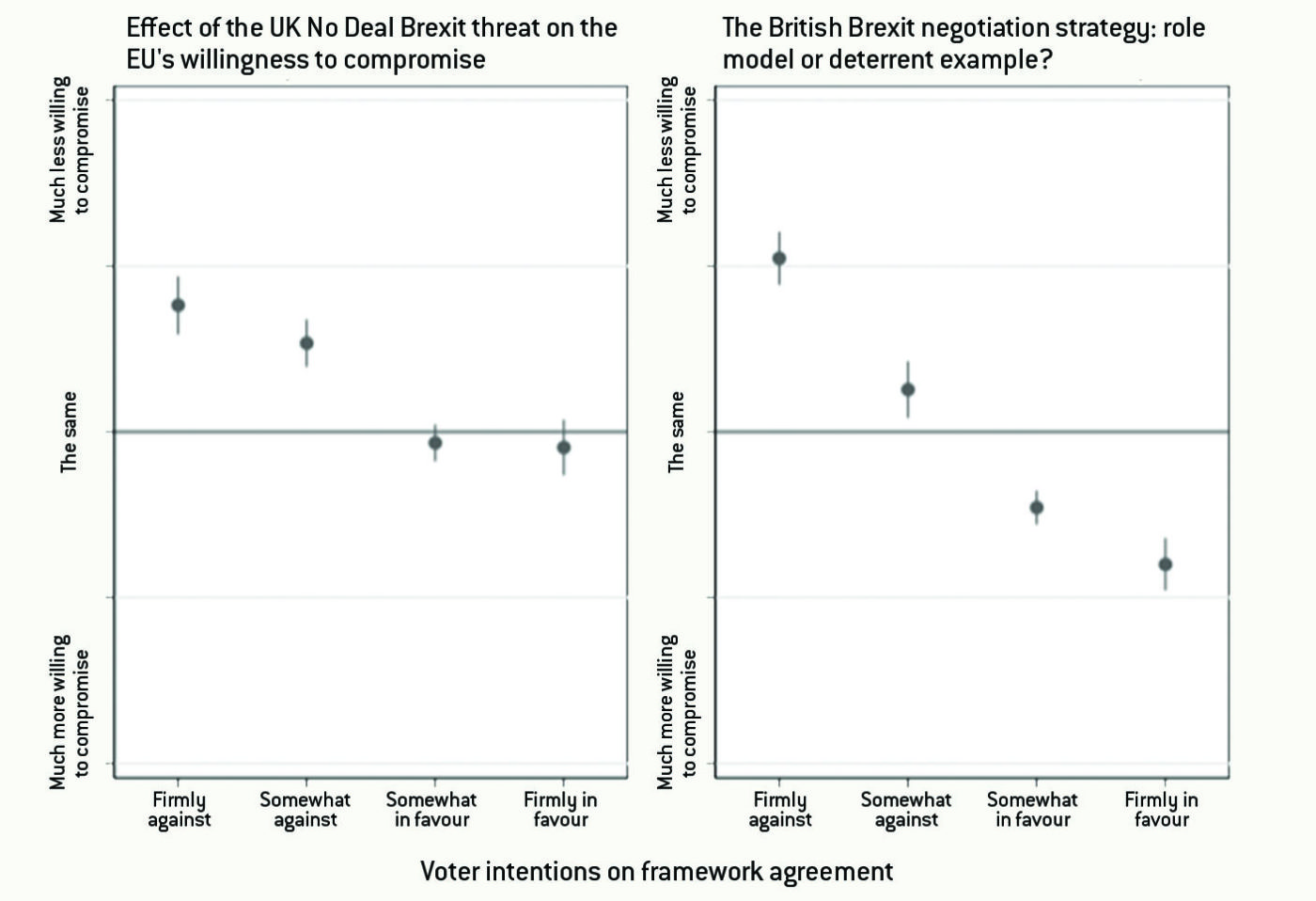

Figure 4 shows that respondents’ opinions

on this question also diverged widely. While opponents of the

institutional framework agreement believed that the British threat to

let the negotiations fail rather than accept a bad deal led to a greater

willingness to compromise on the part of the EU, those in favour of the

agreement saw no effect on the EU’s willingness to compromise.

Together with the perceived low risks of a

failure of the negotiations and the perceived success of the British

threat strategy, it is not surprising that respondents who reject the

institutional framework agreement also tended to see the British Brexit

negotiation strategy as a role model for Switzerland. By contrast,

supporters of the institutional framework agreement tended to see this

confrontational strategy as a deterrent example for Switzerland.

Figure 4: Individual assessments of the British Brexit negotiation strategy, February 2021

Unequal perceptions of supporters and opponents

Overall, it is clear that the political

divide between supporters and opponents of the institutional framework

agreement exists not only at the level of political elites, but can also

be observed among the electorate. It is noteworthy that both sides not

only assess the effects of a conclusion and a failure of the framework

agreement differently, but that they even perceive the status quo of current bilateral relations differently.

Although an erosion of the bilateral

treaties would be a lengthy affair, upcoming EU decisions on

Switzerland’s participation in the European research programme Horizon

Europe, or in the EU COVID-19 certificate scheme, will provide the first

indications as to whether the optimism of the opponents or the fears of

the supporters are justified.

| *Data and Method

Within the framework of the ERC-funded research project The Mass Politics of Disintegration, a group of researchers led by Prof. Dr. Stefanie Walter

at the University of Zurich has collected detailed data on the opinions

of Swiss citizens on Swiss-EU bilateral relations, Brexit and current

debates on European policy, giving an insight into the expectations of

supporters and opponents of the institutional framework agreement.

Within the framework of a four-wave survey, a total of 2633 Swiss

citizens were asked on several occasions for their opinions on Swiss-EU

relations and foreign policy. Figures 1 and 2 refer to the survey period

9-28 September 2020 (N=1493); Figures 3 and 4 refer to the survey

period 8-28 February 2021 (N=1353). |

Republishing and referencing

Bruegel considers itself a public good and

takes no institutional standpoint. Anyone is free to republish and/or

quote this post without prior consent. Please provide a full reference,

clearly stating Bruegel and the relevant author as the source, and

include a prominent hyperlink to the original post.

Bruegel

© Bruegel

Key

Hover over the blue highlighted

text to view the acronym meaning

Hover

over these icons for more information

Comments:

No Comments for this Article