The authors were both involved in preparing the Maastricht summit and examine the arithmetic of the Maastricht reference values in relation to the macroeconomic facts as of today. Broader questions to do with fiscal architecture and institutional design will be addressed in a subsequent column.

The Maastricht fiscal architecture relies on limits on debt and the

general government deficit. The reference values used are 3% for the

deficit and 60% for the debt, both in terms of GDP. These reference

values are not specified in the body of the Treaty. Instead, they are

defined in an annexed Protocol. The expression “reference values” is

used six times when defining the two criteria to be used by the European

Commission when monitoring developments of public finances, with a view

to identifying “gross errors” in the conduct of fiscal policy. These

two reference values have no solid ground in either theory or empirical

evidence. No such a claim was made at the time (or ever).

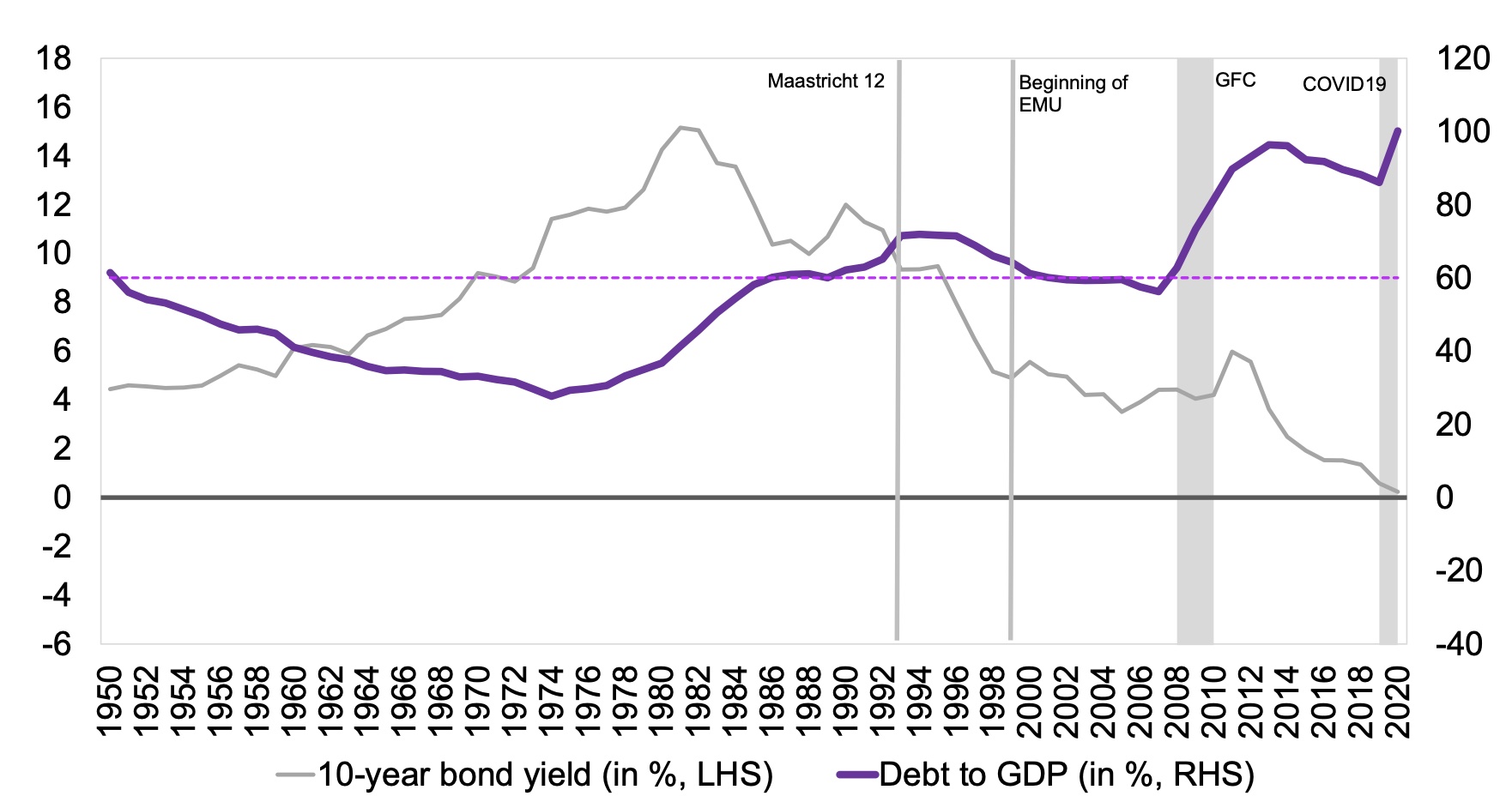

To our recollection, the first reference value agreed was the

debt-to-GDP ratio of 60%. It was a value close to the average of the

negotiating countries at the time (see Figure 1).1 In the

five years up to 1989, the simple average of the debt-to-GDP ratio of

the 12 countries negotiating the Treaty was almost exactly 60%.

The debt criterion did not impose 60% as an absolute limit. Instead,

it specified that if the debt-to-GDP ratio exceeds 60%, it should be

sufficiently diminishing and approaching the reference value at a

satisfactory pace. The idea is that, even if the public debt-to-GDP

ratio is elevated, public finances are under control if this ratio is

moving in the right direction and the reference value is getting closer

fast enough. Such formulation was also necessary for political reasons.

Some countries (Belgium, Ireland, and Italy) had debt-to-GDP ratios

close to (or above) 100% of GDP at the time, and therefore a 60%

absolute limit could not be respected anytime soon. Since the absence of

an excessive deficit was one of the convergence criteria for

participation in monetary union this question was very salient from a

political viewpoint.

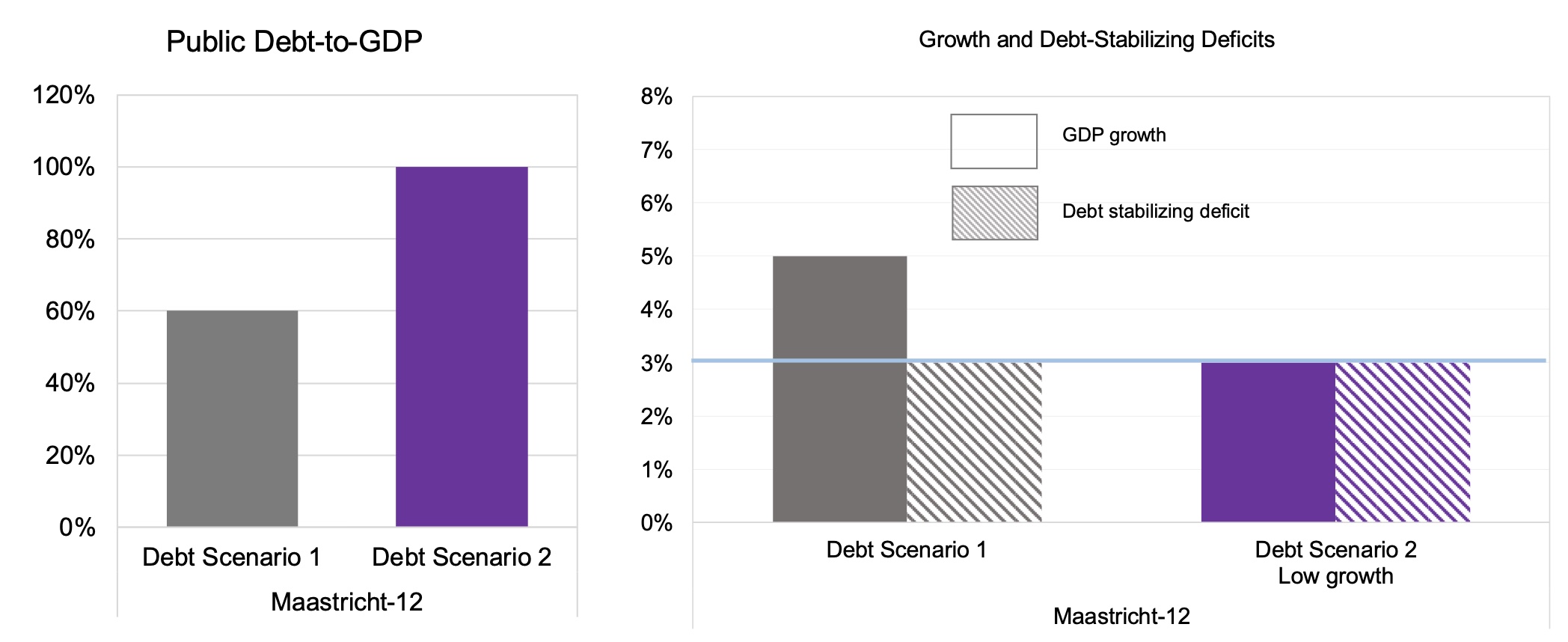

A very simple equation helps to understand the compatibility of the reference values for debt and deficit:

∆b = d – gb

where Δ is the change operator; b is the debt-to-GDP ratio; d is the overall deficit in percent of GDP; and g is the growth of nominal GDP. In turn, g

can be expressed (approximately) as the sum of the growth of real GDP

and inflation. At the time, a reasonable assumption for nominal GDP

growth was 5%. That corresponded to a real growth of 3% (or more) and a

norm for price stability requiring inflation below 2%. With the overall

deficit at 3% the debt-to-GDP ratio would be invariant at 60% of GDP

(see Figure 2, Scenario 1). With debt-to-GDP at bhigh>60% an overall

deficit of 3% implies a declining public debt-to-GDP ratio.

Specifically, it implies:

∆b = -0.05 × (bhigh – 60)

which was not used specifically in the Treaty but may be used to

rationalise the 1/20th rule that was introduced many years after. It can

also be used to elucidate the meaning of the qualifying clause

“sufficiently diminishing and approaching the reference value at a

satisfactory pace.”

The Member States committed to a budget position of close to balance

or in surplus in the context of the Stability and Growth Pact of 1997.

Under such constraint the long run level of the public debt-to-GDP ratio

would be close to zero. The expectation would be that the debt-to-GDP

ratio would approximate such a value at a rate of about 1/20th of the

gap per annum. As is clear from the argument above, if nominal GDP grows

at 5%, a balanced budget implies a much faster fall in the debt-to-GDP

ratio than implied by the 1/20th rule.

The close to balance or surplus requirement also allowed for the 3%

ceiling to be respected in most circumstances. The exceptions include

catastrophes and deep or prolonged slumps. In other words, a balanced

budget position is compatible with the full functioning of automatic

stabilisers over the course of a normal business cycle, while respecting

the 3% deficit ceiling.

The relationship between the main macroeconomic variables is very

different today. Much has been made of the coincidence of very high debt

levels with very low nominal interest rates. For example, for Italy in

1980, public debt was at 56% of GDP; interest payments on the budget

amounted to 4.4% of GDP. During the 1980s, interest payments more than

doubled as a percentage of GDP. In the first half of 1990s, they reached

double digits with a peak at 12.3% of GDP in 1993. Debt ratios also

more than doubled during this period; the peak was in 1994 with 130.3%

of GDP. In 2020, 40 years on, the debt-to-GDP was at about 155% of GDP.

But interest payments on budget are projected to be substantially lower

at 3.5% of GDP. The main change was disinflation. Inflation was above

20% in Italy in 1980. In 2019, the year before the pandemic crisis,

inflation was barely positive (0.6%).

The key features of the Italian data just described can also be seen,

qualitatively, in the set of 12 countries originally negotiating in

Maastricht – namely, substantial increases in debt during the 1980s and

early 1990s, followed by decreases in interest payments, in inflation,

and in GDP growth (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Public debt and interest rates (Maastricht 12)

Today, debt-to-GDP in the same group of countries, the Maastricht 12, is about 100%.

Throughout this column, we focus on the Maastricht 12 countries to

keep the analysis simple (avoiding, for example, the complications of

the changes over time in the composition of the euro area). Nominal

growth in recent times has also been substantially lower than 5% on

average, hovering around 3% for this group. Arithmetically, with these

values a 3% deficit would stabilise debt at around the current levels of

100% and the gap relative to that level would be closed by 3% a year.

The consistency imposed by the arithmetic of debt accumulation may be

read from left to right on Figure 2. But it is also illuminating to

examine the converse link – from deficits to debt.

Figure 2 Debt, growth, and debt-stabilising deficits

The Maastricht Treaty set the 3% as a reference value. The Stability

and Growth Pact hardened the requirement by setting the 3% as a hard

ceiling, respect of which would require a broadly balanced budget in

normal times to allow a free playing of automatic stabilisers in bad

times. In the end, empirical analyses at the IMF confirm that the 3% has

been a salient focal point for fiscal policy, by acting as a ‘magnet’

and hence reducing the occurrence of both large government deficits and

surpluses (Caselli and Wingender 2018). As such, it had a disciplining

effect on fiscal behaviour, but has not led to the creation of

sufficient room for manoeuvre in good times, thereby helping only partly

to correct the inherent pro-cyclical bias in fiscal behaviour. This

shortcoming will be even more relevant in the future given the lower

nominal growth and the expected larger role of fiscal policy in

responding to shocks....

more at Vox

© VoxEU.org

Key

Hover over the blue highlighted

text to view the acronym meaning

Hover

over these icons for more information

Comments:

No Comments for this Article