Nations have accumulated public debt levels not seen since WWII in their efforts to tackle the health crisis and mitigate the ensuing economic dislocation. The private sector has also experienced a run-up in debt, but unlike the Great Mortgaging of the 2000s, this time led by the corporate sector.

We are living through a health crisis that ranks among the worst

since the Black Death in terms of its human toll and its economic

disruption. The consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic have been

mitigated by unprecedented policy responses (Baldwin and Weder di Mauro

2020). On the public health front, rapid interventions and vaccines are

being applied at scale. And monetary easing (English et al. 2021),

fiscal support (Deb et al. 2022), and debt accumulation have all served

as a cushion on the economic side.

The 24th Geneva Report on the World Economy looks at the state of

debt in the world today and what it portends (Boone et al. 2022). Debt

and credit are closely linked to financial crises, to the evolution and

shape of the business cycle, and to the likelihood of negative tail

events. Financial vulnerability is endemic in a highly leveraged world.

In a time of such record-high debt, it is difficult not to be

pessimistic about our future economic, financial, social, and political

stability. One might even conclude that debt needs to be urgently

reduced.

Download Debt: The Eye of the Storm, the 24th Geneva Report on the World Economy, here.

After a new surge in borrowing during the pandemic, everything

still looks quite calm almost two years later. Is debt just the eye of

the storm? Will the smooth absorption of unprecedented debt issuance

endure, or will the strain of this global shock eventually make its

presence felt here too? Where are the weak spots? Our report has several

major themes and, while noting areas of concern as well as massive

uncertainties, we conclude that there are also reasons to be optimistic.

Taking a longer view, debt was already elevated before the pandemic.

Public and private sector debt in advanced and emerging market economies

had surged to unprecedented highs in the past four decades, before

rising further in the pandemic. However, that long-term trend played out

against a backdrop of abundant funding from three main sources – the

savings gluts of the old, the rich, and the rest of the world – and a

context of weak investment.

The drop in real interest rates in both advanced and emerging market

economies at a time when debt was surging suggests that the urge of

creditors to save has far outpaced any shifts in borrowers’ desire to

issue more debt. Our view is that a low real natural rate, r*, is a

structural feature of the global macroeconomy – one largely beyond the

control of policymakers and one that it is likely here to stay for a

considerable time as the underlying forces pushing the world into saving

more remain intact.

Public debt

Public debt in advanced economies has surged due to the pandemic, but

borrowing costs are close to an all-time low and lower than growth

rates (r < g). Central banks have also helped funding conditions in

the short run. While there are plenty of challenges for fiscal policy in

the coming years (e.g. ageing, inequality, digitalisation, the green

transition), the situation in advanced economies appears manageable for

now.

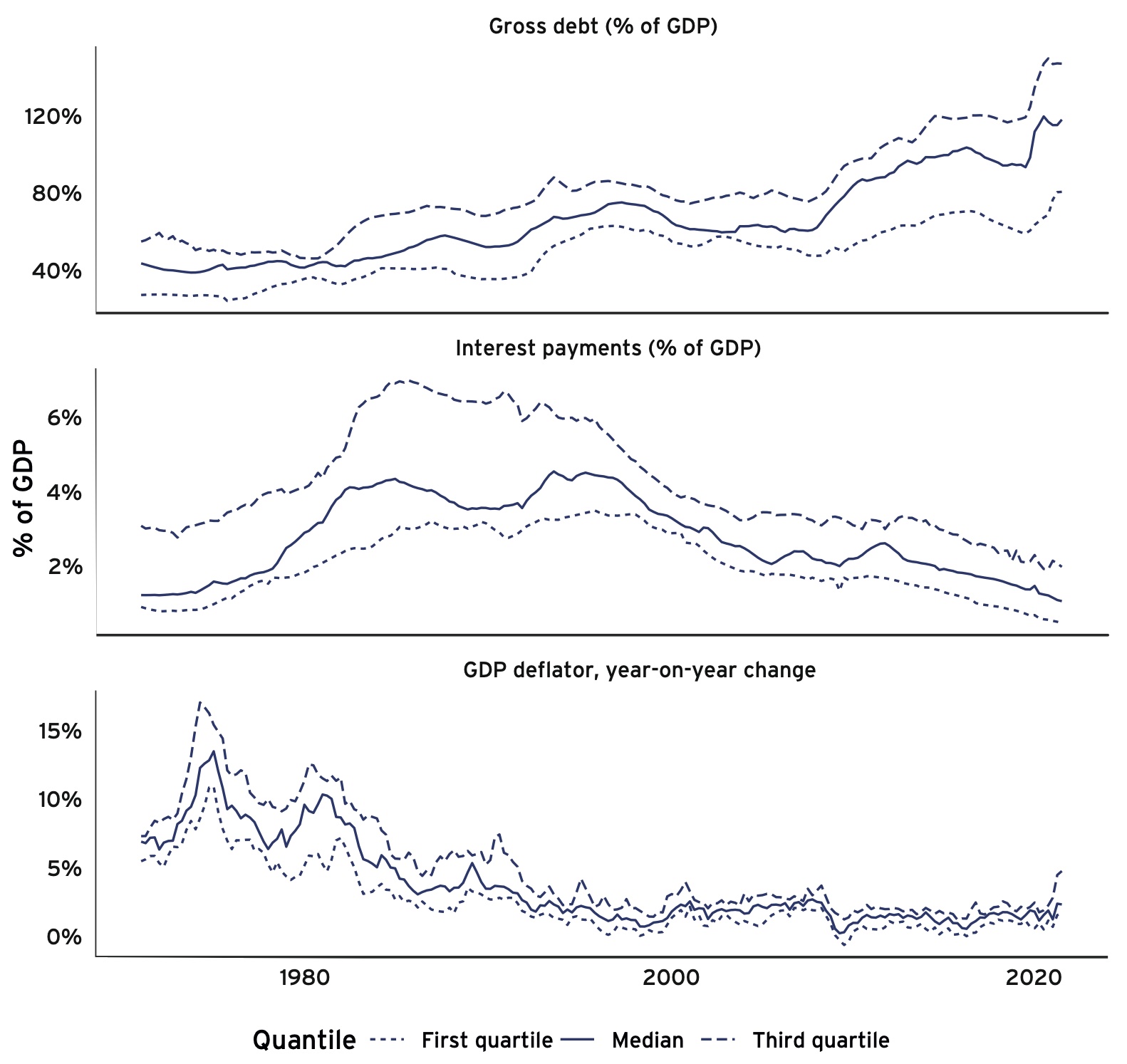

This state of affairs is illustrated in Figure 1 for 15 OECD

economies. The top panel in the figure shows the rapid run-up in public

debt in the past 40 years, from about 40% of GDP in the early 1980s to

over 100% today. However, debt burdens today are about the same as debt

burdens in the 1980s, as the second panel in the figure shows.

Of course, one of the salient features of the world economy at the

time of writing this column is the quick pickup in inflation seen in

nearly all advanced economies. Is higher public debt to blame? The third

panel of Figure 1 would suggest that this might be too premature a

conclusion. At a time when public debt has more than doubled since the

1980s, inflation has declined from a high of about 12% to about 3% right

before the latest pickup in inflation.

Beyond the transitory nature of Covid-related supply disruptions and

their effect on inflation, three narratives have emerged arguing that

inflation may not wane after the pandemic comes under control. The first

narrative, based on the traditional Phillips curve concept, emphasises

the potential for large fiscal stimulus programmes – especially in the

US – to cause an overheating of goods and/or labour markets. A second

narrative ascribes an important role to monetary factors in conjunction

with government debt dynamics. A third narrative, based on the fiscal

theory of the price level, postulates a more direct link between

unsustainable and ‘irresponsible’ fiscal policies and inflation.

At this juncture, the peak fiscal response is behind us. Going

forward, most governments are already planning on bringing their

finances back in check. Second, central banks are either telegraphing or

already adopting a more hawkish stance to monetary policy. Finally, in

an environment where r < g, governments enjoy greater credibility

that they can bring finances back in check before they become

unsustainable. It is perhaps for these reasons that measures of

long-term inflation expectations have remained relatively well anchored

in the face of surging public debt, as Figure 2 shows.

Figure 1 Long term evolution of public debt, government interest payments and inflation in 15 OECD countries

more at Vox

© VoxEU.org

Key

Hover over the blue highlighted

text to view the acronym meaning

Hover

over these icons for more information

Comments:

No Comments for this Article