|

|

The capital markets union (CMU) is one of the cornerstones of the euro area’s financial architecture. But progress in developing it has been slow. Since the agreement on establishing CMU in 2015, many subprojects have been launched, and some completed, but European capital markets are still far from being fully integrated. Despite the fact that the coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis has made CMU more important than ever, progress has unfortunately slowed, notwithstanding the substantial headway made on the fiscal side with the agreement on the European recovery package (Next Generation EU).

Financing the post-crisis recovery is one of the most pressing challenges Europe is facing today. Capital markets will be crucial. The new bond issuance by the European Commission, in the context of Next Generation EU, relies on well-functioning capital markets.[1] But public funding cannot do the heavy lifting alone; it will have to be complemented by substantial private financing. With the banking sector under pressure due to the pandemic, private bond and equity markets can play an important role in complementing bank financing.

In order to recover from the pandemic and strengthen the euro area’s growth potential, a new push is needed towards the long-term ambition of creating a genuine single European capital market that is deeply integrated and highly developed. This will not only mobilise the resources needed to reboot the euro area economy after the global contraction. It will also help meet the additional challenges posed by external developments, such as Brexit and global trade tensions.[2] In addition, it will provide opportunities for accelerating the transition to a low-carbon economy – thereby supporting the European Union’s ambition to be a leader in green finance – and for funding the transition towards the digital economy. A single capital market will also strengthen our common currency’s role on the global stage. And last but not least, a deeper and more integrated financial system is also needed from a monetary policy perspective, as integrated capital markets improve the transmission of our single monetary policy to all parts of the euro area. In turn, this will help limit the risk of growing asymmetries among member countries as our economies recover from the COVID-19 shock at different speeds.

Our aim with this blog post is to re-emphasise the importance of strengthening efforts to advance the CMU project, in the light of the European Commission’s forthcoming new Action Plan.[3] First, we explain why CMU is important, especially due to the COVID-19 crisis. Second, we describe the current state of play regarding capital market development and integration in the EU, and identify the areas where progress is needed most. And third, we set out a roadmap of policy measures that would remove core barriers to further integration. Following this roadmap would benefit the euro area, the EU and its citizens. It would stabilise funding sources for households, companies and governments, foster cross-country risk-sharing and consumption smoothing, and stimulate growth and the post-COVID-19 recovery.

The measures we propose are broad in nature and require strong commitments, in line with the ECB’s long-standing view that the CMU project has to be ambitious.[4] Accomplishing these reforms could trigger a virtuous cycle of better economic outcomes and further reforms, strengthening the European project. We recognise that developing and integrating European capital markets will primarily be a market-led process, so the measures we propose are designed to enable market forces.

Even before the pandemic, the ECB was a strong supporter of the CMU project. CMU aims to deepen and further integrate capital markets in order to establish a genuine single capital market within the EU, which would allow investors, savers, firms and market infrastructures to access a full range of services and products, regardless of where they are located.[5] Let us explain why CMU matters, and why it is particularly important due to the COVID-19 crisis.

First, European firms would benefit from more diverse funding sources, which would allow them to adapt more effectively to changing funding conditions. Easier access to market-based financing instruments would lessen firms’ reliance on bank financing when the banking sector has been weakened by a shock, such as the COVID-19 crisis. This would also support the smooth transmission of monetary policy.

Second, progress towards CMU would increase private risk-sharing across countries and actors, generating positive effects from a macroeconomic stabilisation perspective and making economies more resilient to local shocks. This is particularly important now, with the risk of diverging economic development within the euro area due to the shock from the pandemic. Within Europe, increasing cross-border ownership of stocks and debt securities and cross-border business financing would be an important way of sharing risks and thereby stabilising households’ consumption and firms’ investment over time.[6] Equity markets tend to have particularly strong risk-sharing properties. Several studies also emphasise that equity funding is more resilient to shocks than debt funding, and can be considered more stable from a risk-sharing perspective.[7]

Third, boosting capital markets through policies aimed at increasing equity financing would support growth and innovation. Research suggests that firms with higher growth potential generally resort more to (public or private) equity financing than debt financing and that capital markets are better at financing innovation and new sources of growth.[8] This makes capital market funding particularly attractive with a view to boosting Europe’s potential growth after the pandemic. A fully fledged CMU would improve funding conditions for innovative firms, which would mean brighter prospects for jobs and growth in a more sustainable economy, thereby helping to successfully implement the structural changes that will be unavoidable after the crisis.

Fourth, advancing CMU would speed up the transition to a low-carbon economy. Recent analysis suggests that an economy’s carbon footprint shrinks faster when it receives a higher proportion of its funding from equity investors than from banks or through corporate bonds.[9] Given equity investors’ propensity to fund intangible projects, equity markets might be more successful in funding green innovation and supporting the reallocation to green sectors.

Fifth, integrated euro area capital markets would strengthen the international role of the euro, as deep and liquid financial markets are fundamental to a currency’s ability to attain international status.[10] By reducing transaction costs, deeper markets would make using the euro more attractive for international financing and settlement. More liquid markets also mitigate rollover risk and are thus perceived as safer by investors. A stronger international role for the euro would benefit our monetary policy, including through greater policy autonomy and improved monetary policy transmission, with positive spillbacks and lower external financing costs.[11] It would complement other measures supporting the international role of the euro, such as the expansion of euro liquidity facilities during the COVID-19 crisis.[12]

Finally, progress on CMU would dovetail with another key EU objective: completing the banking union. Banks and capital markets complement each other in financing the real economy, so the two projects are mutually reinforcing.[13] On the one hand, more integrated capital markets support cross-border banking activities, as banks exploit economies of scale and offer similar capital market products across the EU. More cross-border holdings would also allow banks to have more diversified collateral pools for their securitised products and covered bonds. This could ultimately make banks more resilient, as they would benefit from a wider investor base for capital market-based funding instruments and a broader market to which they could sell non-performing assets. On the other hand, a more resilient and integrated banking system supports the smooth functioning and further integration of capital markets. Just as with CMU, the benefits of banking union become even more visible due to the pandemic.

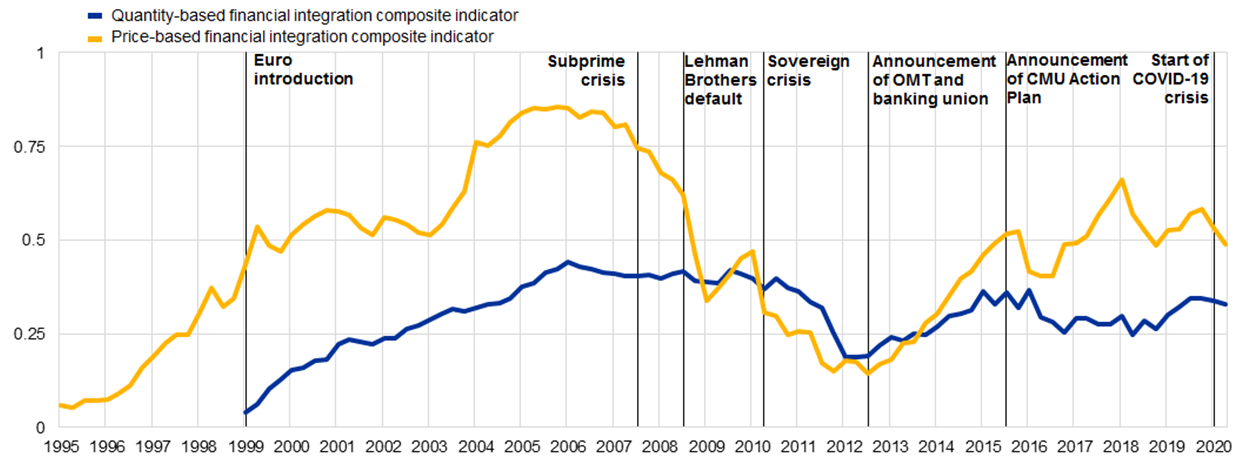

The first CMU Action Plan of 2015 has generated some positive developments in European capital markets. Among other things, it led to some progress on harmonising and improving insolvency frameworks[14] and on establishing a new EU framework for covered bonds and simple, transparent and standardised securitisations. But a significant “CMU effect” has yet to be seen in the data – partly because these measures have only been implemented recently and their full impact will take some time to emerge.[15] European capital markets – and especially equity markets – remain underdeveloped and insufficiently integrated at the European level. While there was a strong positive trend in capital market integration following the great financial and euro area crisis, as shown by the price- and quantity-based indicators in Chart 1, the integration of equity markets has stagnated since 2015 and has even declined since the fourth quarter of 2017. Cross-border holdings of debt have increased, but this is mainly true for shorter maturities, which are less stable than longer-term debt.[16] Another notable trend is that investment funds are playing an increasingly important role in cross-border integration.[17] However, overall risk-sharing is still low compared with the levels typically observed across regions or states within a single country or federation.[18]

While it is too early to fully assess the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on EU capital markets, some initial indicators show that the pandemic has triggered a refragmentation within euro area financial markets, mainly through bond and equity markets. At the height of the pandemic, this meant that our private purchase programmes could not reach the non-financial corporations (NFCs) of all euro area countries in the same way.[19]

Chart 1

Price and quantity-based indicators of financial integration

(quarterly data; Q1 1995 – Q2 2020)

Source: ECB (2020), Financial Integration and Structure in the Euro Area, March 2020.

Notes: The indicators are bound between zero (full fragmentation) and one (full integration). The result of the quantity-based composite indicator for Q2 2020 is based on money market and equity market benchmark data from Q2 2020; for the bond market, Q1 2020 benchmark data are used. For a detailed description of the indicators and their input data, see the Statistical annex to the ECB report “Financial Integration and Structure in the Euro Area” (see source above) and Hoffmann et al. (2019).

Capital market development is also lagging behind.[20] While the US economy is financed through capital markets to a significant degree, the euro area economy continues to be mainly financed by banks and through unlisted shares. Nevertheless, the role of capital markets in providing a stable source of funding to the European economy is expanding, thereby moving the euro area’s financial structure towards a more balanced composition.[21] NFCs have gradually diversified their funding structures and are increasingly financing themselves in the market by issuing debt securities. At the same time, however, corporate bond markets are very uneven across euro area countries.

Even though the share of all equity instruments in total financing in the euro area is comparable to other countries, financing through equity traded on public markets (listed shares) remains relatively uncommon, and well below the levels seen in other major economies.[22] Conversely, loans and unlisted shares account for particularly large proportions of financing in the euro area economy. Similarly, the EU is lacking in early-stage private equity investment (see Chart 2). Data on venture capital investment relative to GDP show that even in Finland and Estonia, which are the most advanced EU countries in this area, the ratio is less than one-fifth of that in the United States. Early-stage financing is not the only ingredient missing for innovative firms to flourish: the EU is also lagging behind the United States as regards an ecosystem that promotes the next stages of growth when firms mature and need to scale up their businesses.[23]