|

|

Future

pension entitlements have also been well protected thanks to the

exceptional policy response to the crisis, according to a new OECD

report.

Pensions at a Glance 2021

says however that the long-term financial pressure from ageing

persists. Pension finances deteriorated during the pandemic due to lost

contributions, and shortfalls have been mainly covered by state budgets.

Putting pensions systems on a solid footing for the future will require

painful policy decisions,

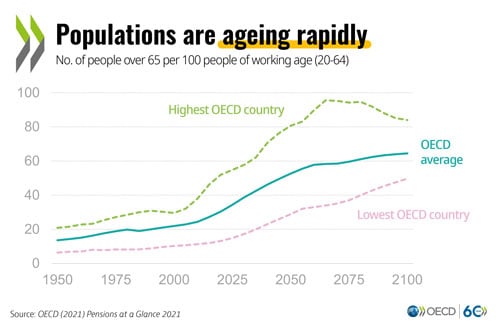

Although

life expectancy gains in old age have slowed since 2010, the pace of

ageing is projected to be fast over the next two decades. The size of

the working-age population is projected to fall by more than one‑quarter

by 2060 in most Southern, Central and Eastern European countries as

well as in Japan and Korea.

Although

life expectancy gains in old age have slowed since 2010, the pace of

ageing is projected to be fast over the next two decades. The size of

the working-age population is projected to fall by more than one‑quarter

by 2060 in most Southern, Central and Eastern European countries as

well as in Japan and Korea.

Young people have been severely affected by the crisis and might see

their future benefits lowered, especially if the pandemic results in

longer-term scarring and difficulties in building their careers.

Allowing early access to pension savings to compensate for economic

hardship, as observed in some countries such as Chile, may also generate

long-term problems: unless future higher savings offset these

withdrawals, low retirement benefits will be the consequence.

Mandatory schemes provide an average future net replacement rate of

62% to full-career average‑wage workers, ranging from less than 40% in

Chile, Estonia, Ireland, Japan, Korea, Lithuania and Poland to 90% or

more in Hungary, Portugal and Turkey.

Over the last two years, many countries significantly reformed

earnings-related pension benefits, including Estonia, Greece, Hungary,

Mexico, Poland and Slovenia. Chile, Germany, Latvia and Mexico also

increased income protection for low earners. Action on retirement ages

was limited. Sweden increased the minimum retirement age for public

earnings-related pensions; the Netherlands postponed the planned

increase while reducing the pace of the future link to life expectancy;

and Ireland repealed the planned increase from 66 to 68 years. Denmark,

Ireland, Italy and Lithuania have extended early retirement options.

Based on legislated measures, the normal retirement age will increase

by about two years in the OECD on average by the mid‑2060s. The future

normal retirement age is 69 years or more in Denmark, Estonia, Italy and

the Netherlands, while Colombia, Luxembourg and Slovenia will let men

retire at 62. Women will maintain a lower normal retirement age than men

in Colombia, Hungary, Israel, Poland and Switzerland.

Pensions at a Glance 2021 says that the biggest long-term challenge

for pensions continues to be providing financially and socially

sustainable pensions in the future. Many countries have introduced

automatic adjustment mechanisms (AAM) in their pension systems that

change pension system parameters, such as pension ages, benefits or

contribution rates, when demographic, economic or financial indicators

change. These automatic adjustment mechanisms are crucial to help deal

with the impact of ageing.

About two‑thirds of OECD countries use some form of AAM

in their pension schemes, adjusting retirement ages, benefit levels and

contribution rates and using an automatic balancing mechanism. OECD

analysis shows that, over the years, the automatic adjustment mechanisms

were sometimes suspended or even eliminated in order to avoid pension

benefit cuts and retirement-age increases. Yet, compared to the

alternative of discretionary changes, AAMs can be designed and

implemented to generate changes that are less erratic, more transparent

and more equitable across generations.