|

|

Brexit has already done considerable damage to the United Kingdom’s financial sector. The EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement did not secure continued market access for UK-based banks to the European Union’s financial sector, as access will depend on future regulatory equivalence decisions. In the wake of the loss of passporting rights for most banking services, about £900 billion in bank assets (or 11% of total UK assets at end-2020) has already moved to the EU. Further shifts of assets, staff and legal entities are likely as European supervisors demand that fully functional units be established within the EU. Nevertheless, despite this diminished post-Brexit stature, the UK banking sector in late 2020 remained the largest globally in terms of cross-border claims, and the second-most important in terms of foreign claims consolidated within the home base of internationally active banks. The liquidity, human capital and financial services ecosystem in the UK is as yet unrivalled by any financial centre within the EU.

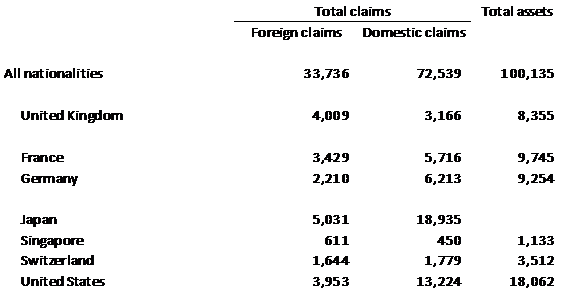

Table 1: Consolidated banking statistics, by nationality of reporting bank, end-2020, (US$ billions)

Source: Bruegel, based on BIS consolidated banking statistics.

The complexity and size of the UK banking sector (which is equivalent to roughly five times UK GDP) brings with it significant financial-stability risks. Post-Brexit, UK policymakers therefore envisage a distinct style of regulation and supervision, though do not call for a complete revamp of how it was done while the UK was still in the EU. There are nevertheless concerns in the EU that the UK could embark on wide-ranging deregulation, in an effort to build a more international financial centre (dubbed ‘Singapore-on-Thames’). As detailed in a Bruegel paper for the European Parliament, divergence between the two systems is indeed inevitable. However, the UK’s adherence to international norms, crucially the Basel framework, is not in doubt. In fact, this adherence to international norms is now enshrined in UK law, including the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement. The extensive engagement of UK banks in international markets and what will in future become a more agile style of UK regulation, nevertheless call for continued close coordination between EU and UK regulators and supervisors.

Strict rules

While still within the EU, the UK built a reputation for strict regulation and supervision, often ‘gold-plating’ EU standards. The UK’s ring-fencing of bank retail units, for instance, is unique in Europe. Ring-fencing has reduced systemic risks and improved the options for resolving failing banks. In some areas the UK insisted on distinct rules for the local financial market (for instance relating to the compensation of senior banking executives), though rules on the safety and soundness of banks and investment firms were as strict as in the EU, if not more so. Well before the end of the Brexit transition period, all key elements of EU financial regulation, including the latest elements of the Basel III framework, were ‘on-shored’ into UK law. The UK hence ended the transition period in December 2020 with its banking regulation closely aligned with that of the EU.

The UK’s new financial services law of April 2021, one of the first pieces of legislation outside the EU, confirmed this commitment to international norms, though it also signalled some significant new directions. Alongside other considerations, the Bank of England will need to take into account in its rulemaking the competitiveness of the UK financial markets (this is common also in other financial centres, including Australia, Hong Kong and Japan). This could be significant, because in future considerable regulatory powers are likely to be delegated to the Bank of England. The UK government has said that a future regulatory framework will be defined in a way that greater flexibility and ability to respond to changes in international markets and standards can be squared with predictability of regulation and the Bank’s accountability to the UK Parliament. Greater flexibility and responsiveness on the part of the regulator could be important once financial institutions revamp their data management and begin to deploy artificial intelligence to a greater extent. Fintech firms in the UK may well benefit from a special regulatory regime.

A further likely change in UK post-Brexit financial regulation will be a simplification of the regime for smaller banks. Originally, the Basel regime was designed only for internationally active banks. Only for these were the objectives of a level playing field and prevention of competitive distortions between banks relevant, as laxer prudential standards could result in cross-border spillovers. As the more complex Basel III framework was introduced, many jurisdictions began to make use of so-called proportionality provisions already envisaged in the Basel Accord, exempting smaller institutions from all but the most essential provisions. The EU remains exceptional in largely rejecting such carve-outs for smaller banks. The EU Capital Requirements Directive requires more-or-less uniform treatment across the single market and for all types of institutions, though of course there is some differentiation in supervision. Outside the EU, the UK is set to reduce the regulatory compliance burden for banks that are small or not active in international markets. As smaller banks grow, additional requirements would be introduced gradually. This will likely intensify competition within the UK banking market and restrain the market dominance of the larger banks.

Supervision by the Bank of England

The pursuit of several parallel objectives has also shaped the work of the Bank of England as the UK’s principal financial sector supervisor. Competition within the UK market is a secondary objective in law, and several other objectives have been announced, such as financial inclusion and mitigating risks from climate change. Again, this is not unusual by the standards of other large jurisdictions. The European Central Bank’s work in banking supervision in the euro area is exceptional in being exclusively focused on financial-sector stability and the safety and soundness of institutions.

As yet, these multiple mandates do not seem to have distracted the Bank of England from its core work on the safety and soundness of institutions. Since 2016, the Bank has continually reviewed banks’ internal risk models, which are crucial in determining risk-weighted assets, and hence capital adequacy. A similar ECB review has recently concluded, resulting in over 250 decisions that required substantial revisions. Limitations on the use of banks’ internal models, known as ‘guardrails’, are set to be included in regulation as the very final elements of the Basel framework at the end of a lengthy transition period. This could be an important test of the credibility of UK and EU banking standards.

A period of financial liberalisation provided the original motivation for rules establishing a level playing field and common standards in regulatory capital. Brexit is obviously a reversal in this process of integration, though large UK and euro-area banks still compete in the same international market. In their home bases, banks should be regulated based on comparable norms. A high-quality supervisory regime in the UK may in fact attract institutions which expect to benefit in terms of reputation and funding costs. The UK and euro-area supervisors have a shared interest in alignment with the Basel framework at a common and comparable high standard, and in strengthening bilateral dialogue.