|

|

The Japanese and UK governments launched a bilateral trade negotiation on 9th June 2020 to create an “ambitious, high standard and mutually beneficial” Free Trade Agreement (FTA) based on the EU-Japan EPA.[2] The parties are aiming to conclude the FTA by the end of the post-Brexit transition period on 31 December and make a swift transition from the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) on 1st January 2021 so as not to interrupt business.

Although the political incentive to achieve the FTA is mounting on

both sides, there is a lack of in-depth multi-disciplinary analysis

which captures the whole picture of the negotiations. This paper aims to

examine the issues we should consider when assessing its value. First, I

argue that there are two key underlying challenges for this

negotiation. Then I discuss what should be prioritised to make the

Japan-UK FTA ambitious, taking into account the unprecedented short

negotiating timeframe. Lastly, I address a few other outstanding issues

and propose a possible mechanism to cope with unfinished business in

order to make the agreement truly valuable from the long-term point of

view.

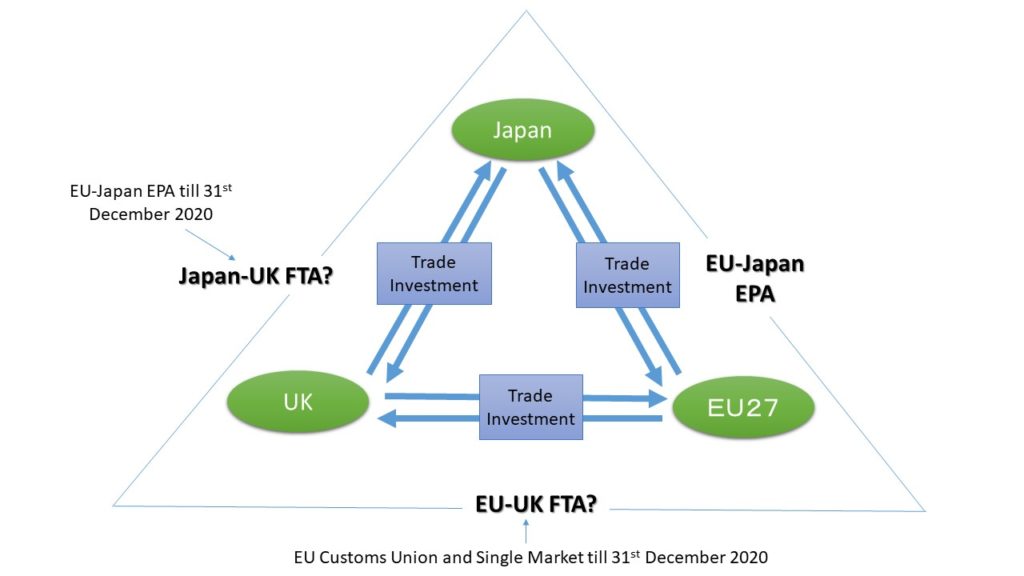

There are two significant challenges underlying the Japan-UK FTA negotiation. The first is that the Japan-UK FTA on its own cannot reflect the EU-Japan-UK trilateral relationship. Although the Japan-UK FTA negotiation is a completely independent bilateral negotiation from the EU-UK future relations, the EU-UK FTA does matter for business because the Japan-UK trade and investment relationship constitutes one side of the EU-Japan-UK trilateral relationship. (Figure 1).

This trilateral trade and investment relationship is the product of Japanese and UK firms’ engagement in Global Value Chains (GVCs) and supply chains in Europe. For Japanese business, this trilateral relationship is particularly important. As widely known, since the 1980s, Japanese firms have established a business model in Europe of using the UK as a hub for business in Europe or a gateway to the EU market. The precondition of this business model was that the UK is an EU member state. In other words, free movement of goods, services, people and capital as a part of the EU Customs Union and the Single Market were taken as granted.

The end of frictionless trade between the EU and the UK after the Post-Brexit transition period directly impacts the current Japanese business model. According to a survey, the top concern of Japanese companies doing business in the UK and the EU is the EU-UK future relationship. Notably, border frictions created by new border controls and customs procedures; tariff rates; and ending the free movement of people are listed as the factors that impact most heavily on Japanese business in Europe, especially manufacturers. Given that these factors threaten their day-to-day business, their interests in the Japan-UK FTA are overshadowed.[3] Of course, British firms also have far more at stake in the EU-UK FTA than the Japan-UK FTA and ration their attention accordingly.

The second underlying challenge is to strike a balance between “continuity” and “ambition”. The Japanese government expressed the necessity to complete the bilateral negotiations by the end of July, in order to fit the outcome into its domestic legislative process. This means a negotiation timeframe is less than two months since the negotiation has launched on 9th June. Even though the negotiation is based on the EU-Japan EPA, the negotiating timeframe is unprecedentedly short.

Both governments are currently negotiating a deal that prioritises “continuity” because high-level political pressures for achieving “continuity” are mounting. The UK government has recently conceded that a UK-US FTA will not be concluded before the US Presidential election this autumn despite the strong desire to make it a central in the “Global Britain” agenda. [4] Accordingly, striking a trade deal with Japan, the world’s third-largest economy, is expected to be the first major FTA deal for Post-Brexit Britain. For the Japanese government, there is strong pressure from Japanese business to achieve a smooth policy transition from the EU-Japan EPA to the Japan-UK FTA on 1st January 2021 in order to avoid business destructions.

On the other hand, Japan is wishing to pursue an “ambitious” FTA with the UK. It was Japan that rejected rolling over the EU-Japan EPA. There were two reasons for Japan’s rejection.[5] One reason is that Japan wanted to achieve a higher level of liberalisation and rule-making in the areas where Japan could not reflect its interests when it negotiated the EPA with the EU. This unfinished business for Japan includes immediate elimination of auto tariffs; an innovative chapter on digital economy; and a comprehensive investment chapter encompassing liberalisation, protection and dispute settlement. The second reason was the domestic legislative procedure. Even though Japan had concluded a “continuity agreement” with the UK which completely replicated the EU-Japan EPA, the Agreement was regarded as a new FTA. This means that it requires a formal approval procedure to pass the Diet (Parliament) of Japan, which is always time-consuming and not a straight-forward process. Once the continuity agreement is approved, it would become almost impossible to renegotiate.

From the UK’s point of view, a great advantage of making a new FTA

with Japan is that it can directly reflect its economic interests. When

the EU-Japan EPA was negotiated, the UK interests were marginalised and

focus was given more to exports of agri-food products and processed

agricultural products, non-tariff barriers on goods (i.e. TBT, SPS) and

trade and sustainable issues. By creating a new FTA based on the

EU-Japan EPA, the UK could focus on its economic interests, such as

services trade and digital trade.

Then, in what way could both governments strike a balance between “continuity” and the scope and level of “ambitions”? Trade negotiations can be categorised into market access negotiations and rule-making. In the case of the Japan-UK FTA, market liberalisation in goods and services cannot be expected except for some outstanding issues, such as accelerating the schedule of tariff eliminations and inclusion of sectors currently exempted from the EPA.[6] For example, Japan shows strong interest in the UK’s immediate elimination of the auto tariffs (the current MFN tariff is 10%), which are scheduled to be eliminated in eight years in the EU’s commitments. In services, including audiovisual services, which is exempted from the EU-Japan EPA, due to EU’s principle on protecting the diversity of cultural expression, would be of mutual interest to Japan and the UK.