|

|

Even when revenues from the tax are redistributed to households so as to make the policy progressive, most people think that they and low-income households would lose out, and that the policy would not be effective at reducing emissions. Public investments and standards could help foster support for an ambitious climate policy.

While 5,000 economists called for the rapid development of carbon taxation in the US and in Europe,1 the public often opposes this climate policy (Carattini et al 2018, Klenert and Hepburn 2018). In France, the government abandoned its plan for an ambitious carbon tax trajectory following the protests of the ‘yellow vests’.2

Why do citizens often oppose carbon taxation? Two common explanations are that citizens refuse to bear the full costs of climate change mitigation for lack of altruism, or that they disagree with the way those costs are distributed. In a new paper (Douenne and Fabre 2022), we argue that a third mechanism may come into play — even when people are expected to benefit from carbon taxation, pessimistic beliefs about the effect of the policy could lead them to oppose it. It is not intuitive that people could benefit from carbon taxation. Actually, carbon taxation alone is generally regressive because poorer households spend on average a larger share of their income on polluting goods. Yet, since they spend less on these goods than richer households in absolute terms, it is sufficient to transfer the proceeds of the tax as a uniform transfer (a policy known as a carbon tax and dividend) to design a progressive policy and make a majority of people better-off (Pizer and Sexton 2019, Douenne 2020, Paoli and van der Ploeg 2021).

We assess attitudes towards a carbon tax and dividend in France during the yellow vests movement. We created a survey administered over 3,000 respondents representative of the French population in February/March 2019. We presented to respondents a budget-neutral €50/tCO2 carbon tax and dividend policy, with information on the effect on energy prices (e.g. +€0.11 per litre of gasoline) and the transfer that each household would receive (€110/year for each adult). We find that people largely reject this proposal — only 10% of our survey respondents approve, while 70% do not accept the reform. This level of rejection is very high compared to what has been measured before or after the yellow vests movement, where about half of the population is found to accept an unspecified increase in the carbon tax (ADEME 2020). Thus, a first insight from our survey is that public opinion can be very volatile and strongly reacts to contemporary events.

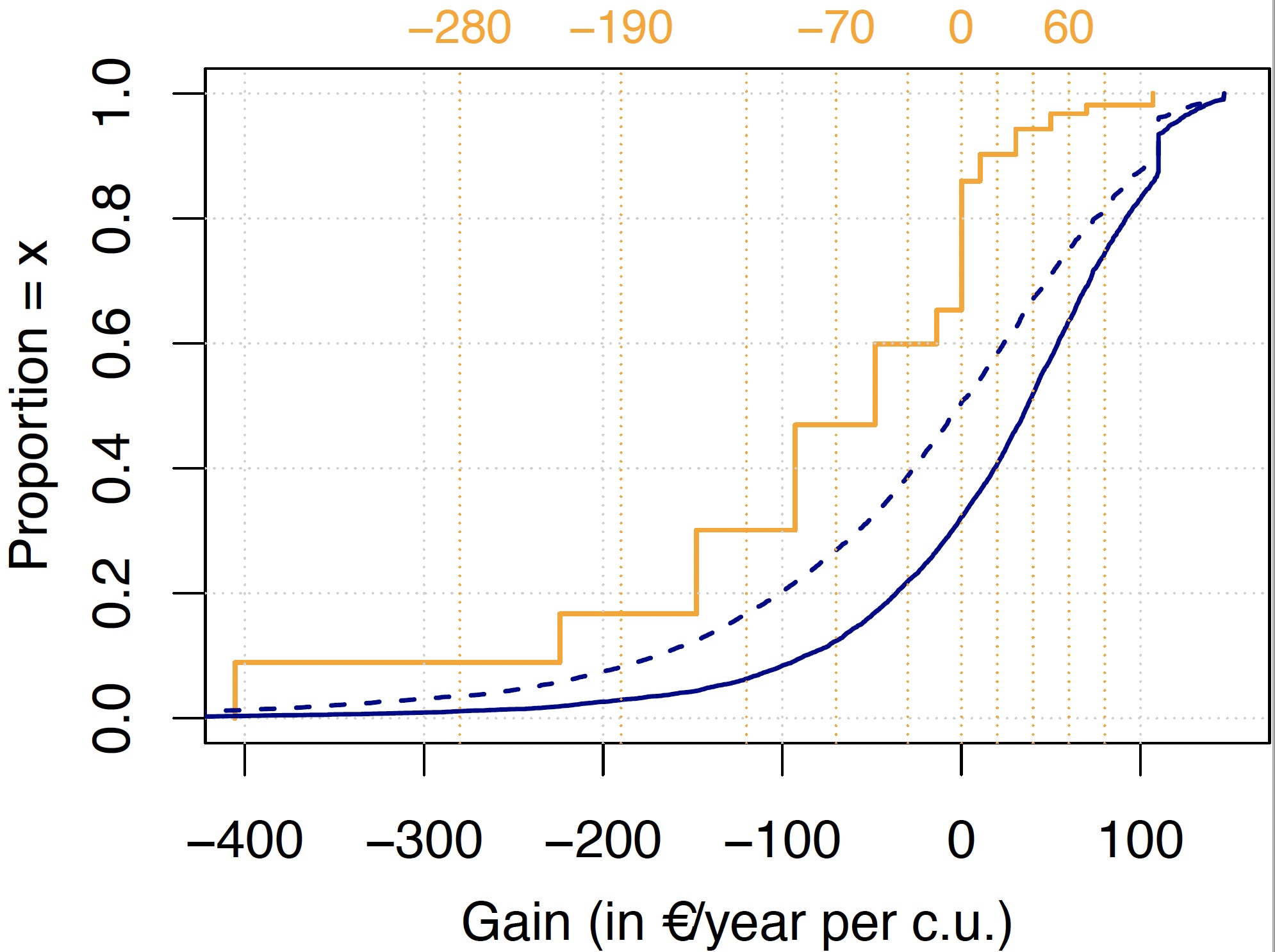

Figure 1 CDF of objective (dark blue) versus subjective (orange) net gains from our tax and dividend

Note: Dashed blue lines represent distributions of objective gains in the extreme case of totally inelastic expenditures. Vertical dotted orange lines show the limits of intervals answers of subjective gains.

We then show that people hold pessimistic beliefs about the policy. Using household budget survey data, we estimate that 70% of households would benefit financially from the policy (see the solid blue line in Figure 1). In our own survey experiment, we ask respondents to estimate their expected gain or loss from the reform (we proceed step by step, asking separately for the impact on their heating and transport expenditures). Only 14% think that their household would benefit from the reform. This pessimism cannot be explained by an ignorance of price elasticities, as respondents correctly estimate them in another question, and the gap between perceived and actual net gains would still be too large if respondents assumed that their expenditures were inelastic. Similarly, respondents are pessimistic about the distributional and environmental effects of the policy. Only 20% believe that the policy would benefit poorer households and 17% think that the policy would be effective in reducing polluting and fighting climate change.

We also find that

the more people are opposed to the policy, the more pessimistic they

are, and that the causality between beliefs and opposition runs both

ways. On the one hand, when provided with new information about the

policy, people discard positive news but correctly process negative

ones. This phenomenon is stronger for people who initially oppose the

policy or who feel close to the yellow vests, which is consistent with

the endogenous formation of beliefs through motivated reasoning. In

other words, the less people like the policy, the less likely they are

to assimilate positive information about it. On the other hand, our

survey design enables us to show that beliefs also causally determine

support for the policy. When convinced that they would gain financially,

people’s likelihood of accepting the policy increases by 50 percentage

points. Similarly, the likelihood of supporting it is 40 percentage

points higher when people are convinced that the policy would

effectively reduce emissions.