|

|

In the years since the global financial crisis, non-bank financial intermediaries (NBFIs) have shown continuous growth, and now account for more than half of global financial assets.[1]

Although there are a variety of reasons for this development, one of the factors has been the stricter banking regulation adopted after the global financial crisis constraining the risk-taking of banks.[2] The regulatory reforms of the last decade have promoted financial stability, especially in the banking sector.[3] At the same time, these reforms have been accompanied by an expansion of actors outside the regulatory perimeter.

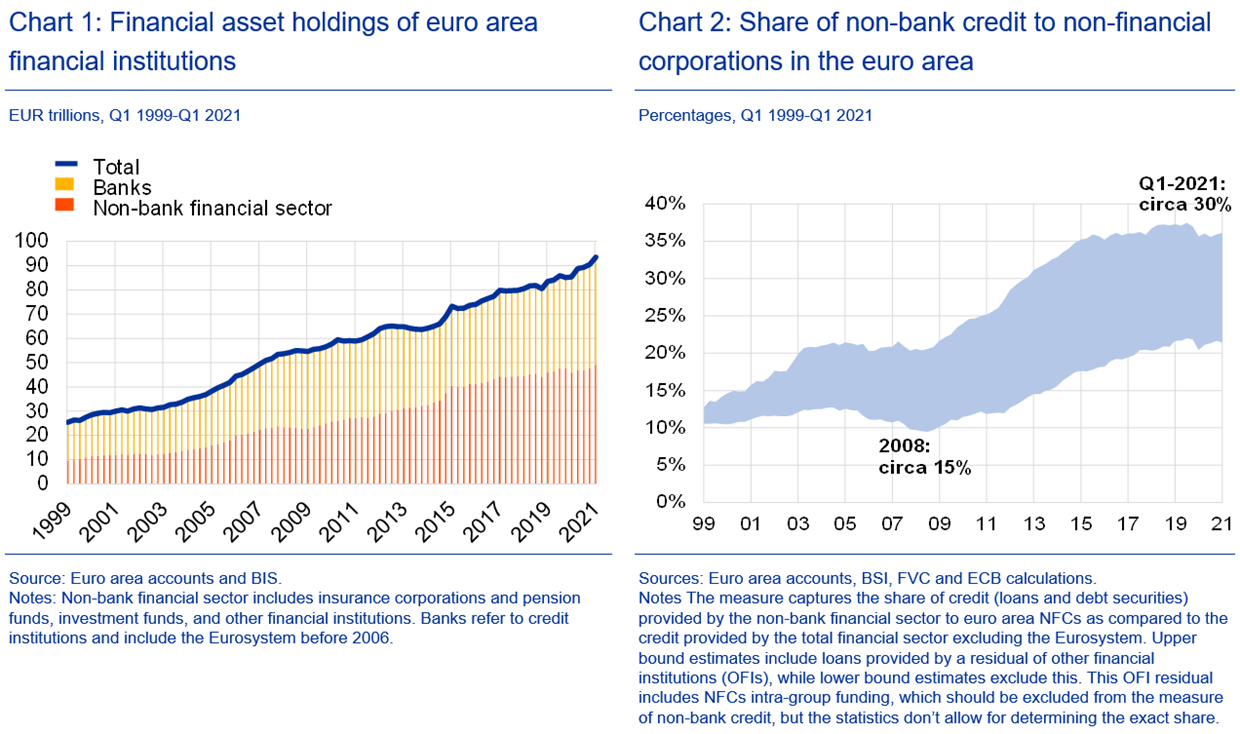

NBFIs have grown faster than banks over much of the past decade: in the euro area, their assets have almost doubled, reaching €48 trillion in December 2020 (Chart 1). In the same period, non-bank finance has become an important source of funding for the real economy: its share of credit to non-financial corporations has increased from about 15% to 30% (Chart 2).

The growth of NBFIs is not the only factor shaping the rapid change of global financial markets. Digitalisation is challenging traditional financial intermediation, for example through the emergence of decentralised finance platforms that are becoming increasingly used. But we can expect more disruptive changes if two related – but up to now parallel – trends eventually converge.

On one side, global technological companies – or “big techs”, such as Google, Amazon, Facebook and Apple (GAFA) – have started offering financial services and, given their size, their large customer base and their access to unique information, are becoming more and more relevant global players in the markets. On the other side, digital assets such as crypto-assets and stablecoins are growing rapidly, although their take-up and reach in payments has remained limited so far. If big techs start issuing global stablecoins, we could see these two trends meet and alter the functioning of global financial markets.

Today, I will argue that if we are to address the cross-border challenges stemming from the expansion of NBFIs, we not only need to strengthen the regulatory and macroprudential approach to these institutions, we also need to widen the regulatory perimeter.

It took the global financial crisis to overhaul the regulation of banks and the coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis to trigger discussions on a more robust framework for money market funds, investment funds and margining practices. We should not wait for another crisis to regulate an increasingly digitalised finance with new global players.

Non-bank financial intermediation can bring benefits to both investors and the real economy across the globe. It allows firms to diversify their sources of funding, including across borders. This diversification can promote risk-sharing, thereby reducing the impact of country-specific or banking sector-specific shocks on the real economy and strengthening financial stability.

At the same time, if underlying risks and vulnerabilities are not kept in check, they have the potential to affect financial stability, both domestically and globally.[4] The financial shock at the onset of the coronavirus pandemic last year is a case in point: while the banking sector proved to be relatively resilient, vulnerabilities were revealed in parts of the non-bank financial system.[5]

From a cross-border perspective, three factors increase the risk of contagion through non-bank financial intermediation.

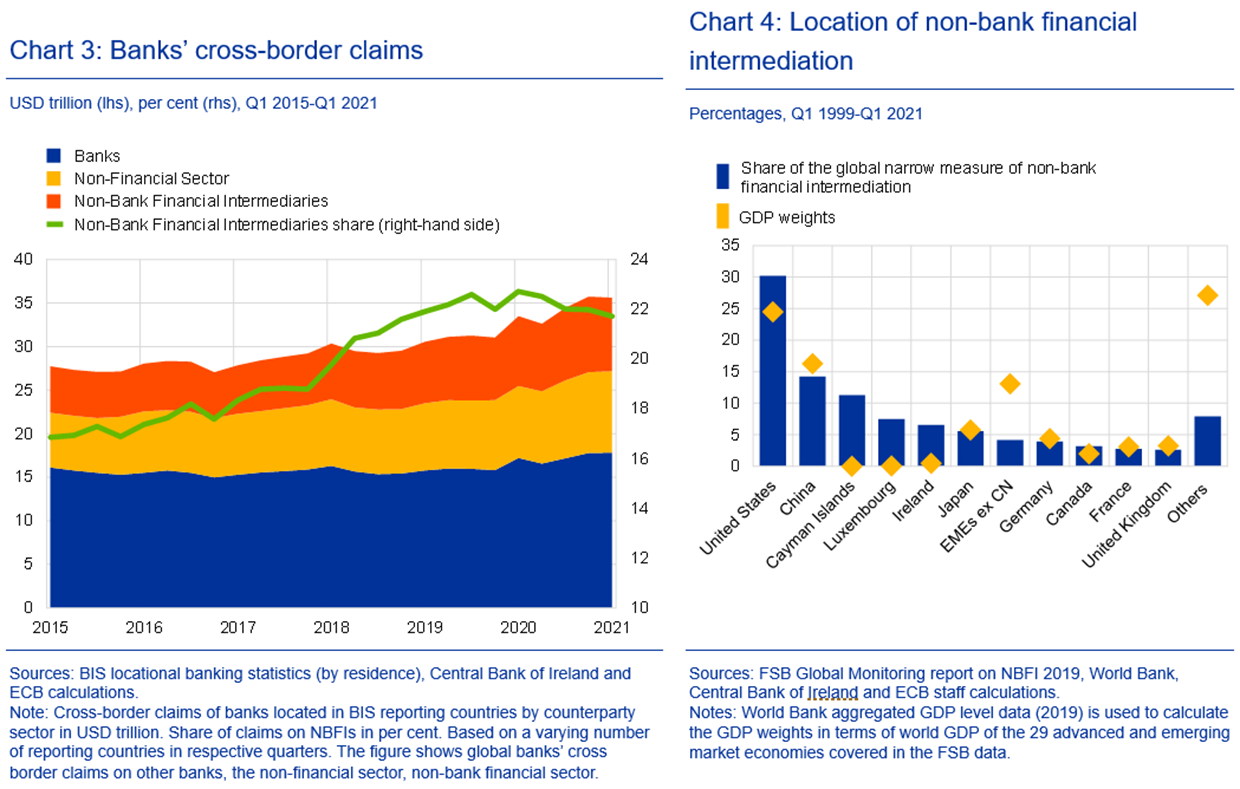

First, NBFIs are highly interconnected at the international level. This is due to their cross-border activities, but also to their interdependencies with the banking sector. Banks own asset management companies operating in multiple countries, provide liquidity to global NBFIs, or invest in their shares.[6] Globally, banks’ cross-border claims on NBFIs have been constantly growing over the past five years (Chart 3).[7]

Cross-border activity can foster international diversification and risk-sharing.[8] At the same time, it increases the risks of contagion and spillovers from a sudden loss of risk-appetite among NBFIs or a sudden loss of confidence in some NBFIs. Moreover, in a system with a higher share of fund-intermediated cross-border flows, monetary policy shocks can be propagated across borders more quickly and forcefully.[9] When economic conditions diverge, this may have adverse consequences for foreign jurisdictions, as was the case in the “taper tantrum” of 2013.[10]

NBFIs are often located in financial hubs, both regional and global (Chart 4). This geographical concentration is higher than for banks and it is driven by several factors such as network effects, human resources and legal systems. In certain cases, exploitation of regulatory or tax arbitrage is also likely to play a role.

The high concentration poses a particular challenge for effective supervision and risk monitoring. The migration of financial activities to foreign financial centres could affect the complexity and transparency of such activities, making it more difficult for domestic authorities to curtail systemic risk. It will also make it more challenging for authorities to coordinate with each other in a crisis and, if necessary, intervene.

more at ECB