|

|

It is a pleasure to welcome you on behalf of the European Central Bank (ECB) to the fifth annual meeting of the International Finance and Macroeconomics Program of the Central Bank Research Association (CEBRA). This year’s meeting is taking place virtually. And it brings together participants from nearly 20 time zones, which is fitting for a conference that seeks to shed light on how digitalisation is changing money and finance globally.

In my remarks today, I will focus on the international dimension of central bank digital currencies, or CBDCs. The ECB launched an investigation phase for the digital euro over the summer.[1] One of the aspects we are investigating is whether it would be possible to use the digital euro in cross-border contexts, and under which conditions. Many other central banks are reflecting on whether they would allow non-residents to access their own digital currency if they were to decide to introduce one.[2]

Decisions about the issuance and design of CBDCs require a careful assessment of the trade-offs between risks and opportunities. The international dimension makes that assessment more challenging still. So, it is already worth thinking about the implications of the cross-border use of CBDCs.

This is where research can help policy. The international dimension of CBDCs is almost unexplored in terms of research. The Latin phrase “hic sunt leones” – here be lions – was used in pre-Renaissance maps to identify uncharted territories that could potentially be dangerous. And in the realm of digital currencies, just like in the pre-Renaissance world, we need research to map those territories. To replace myths with knowledge. To provide the conceptual backbone and evidence that guide our thinking. And to point to the opportunities and challenges ahead.

The literature on the international aspects of CBDCs is still in its infancy. Many of you are contributing to this literature. After reviewing what we already know about the international dimension of CBDCs, I will discuss today open questions of direct policy relevance, in particular: what is different about CBDCs compared to alternative monetary and financial instruments? And how much international cooperation do we need in view of externalities from CBDC issuance, interactions among CBDCs, and the emergence of other innovations such as global stablecoins?

In international fora, the ECB is also involved in technical and policy discussions on how CBDCs could facilitate cross-border payments through different degrees of integration and cooperation – ranging from basic compatibility with common standards to establishing international payment infrastructures.[3] Today, however, I will focus on aspects that are relevant for research on international macroeconomics and finance.

Let’s start by considering what we already know about the international dimension of CBDCs. Available research points to three main implications of allowing non-residents unrestricted access to a given CBDC.

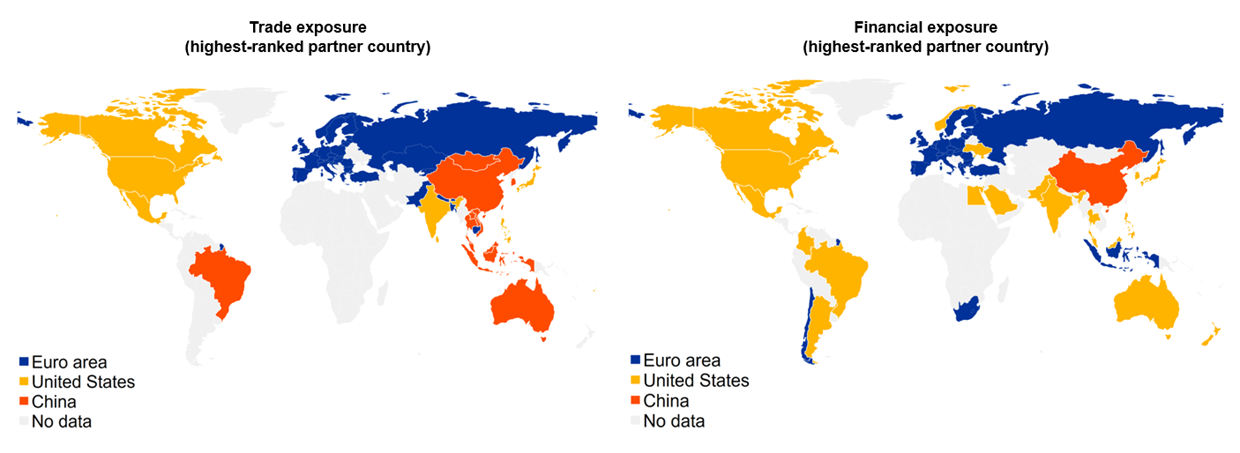

First, a CBDC that can be used outside the jurisdiction where it is issued might increase the risk of digital currency substitution – or digital “dollarisation”.[4] If a foreign CBDC were to be widely adopted, this might lead to the domestic currency losing its function as a medium of exchange, unit of account and store of value – ultimately impairing the effectiveness of domestic monetary policy and raising financial stability risks. These risks are particularly relevant for emerging markets and less developed economies that have unstable currencies and weak fundamentals. Currency substitution could also occur in small advanced economies that are open to trade and integrated in global value chains.[5] Since international trade and finance are complements to each other, financial integration may matter, too.[6] It is hard to gauge in advance how significant the risks of digital currency substitution could be, and in which currencies this substitution could occur. Trade and finance linkages with the issuers of international reserve currencies – the United States, the euro area and China – vary considerably across countries (Chart 1). That, in turn, suggests that the risks of currency substitution vary significantly across countries and currencies. In any case, the introduction of a CBDC in one jurisdiction must do no harm.[7] In particular, it must not put the financial system of other jurisdictions at risk.

International trade and financial linkages with the United States, the euro area and China

Sources: ADB MRIO 2019, IMF CPIS, Haver Analytics, IntLink and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: International trade and financial exposures as of 2019. Trade exposures vis-à-vis the United States, the euro area and China are calculated based on Belotti, F. et al. (2021), “icio – Economic Analysis with Inter-Country Input-Output tables”, Stata Journal, forthcoming. Financial exposures are calculated as the sum of total portfolio investment assets and liabilities of a country held in either the United States, the euro area or China. All data are in US dollars. The financial exposures to China include Hong Kong....

more at ECB