|

|

In this column, two of the organisers highlight some of the main points from the papers and debates, including whether globalisation is reversing, implications of climate change, options for formulating the ECB's inflation aim, challenges with informal monetary policy communication, relationships between financial stability and monetary policy, how to make a monetary policy framework robust to deflation or inflation traps and the role of fiscal policy for the recovery from the pandemic.

The 2020 ECB Forum was one of the “ECB listens” events through which the ECB collects the views of relevant outside parties on its monetary policy framework. Policymakers, academics and market economists debated the implications of selected key structural changes that have a bearing for how monetary policy works in the euro area, combined with discussions on core topics featuring in the strategy review. We group some of the main issues debated in five sections below. All papers, discussions and speeches can be found in the conference e-book (ECB 2021). Video recordings of all sessions are available on the ECB website.

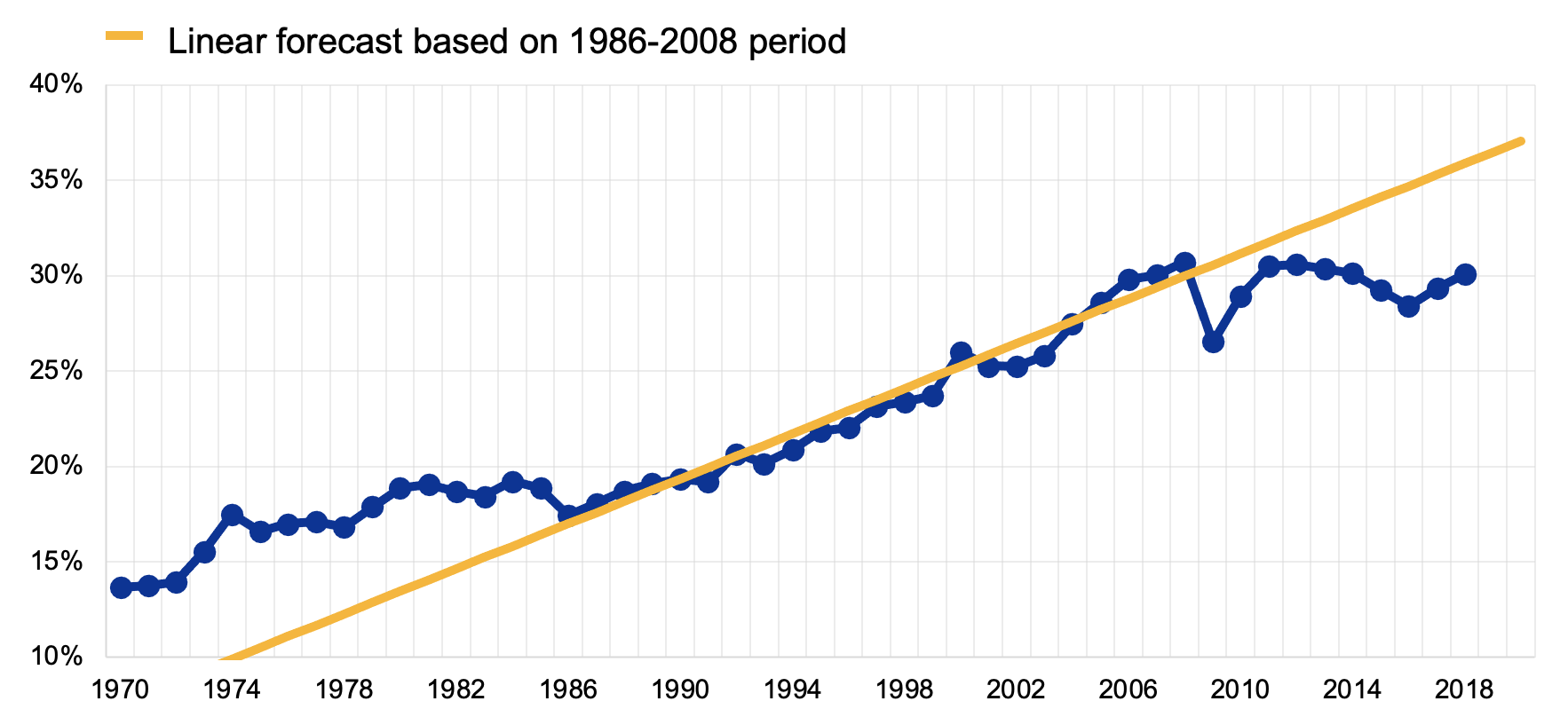

One of the key structural changes in the world economy over the last decades was globalisation. But since the Global Financial Crisis and with the rise of populism, the issue has emerged as to whether this process is reversing to ‘de-globalisation’. Pol Antras (in Antras 2021) argues that international trade and supply chains have slowed but not reversed (‘slowbalisation’) and may be regarded as not likely to turn to de-globalisation. The backward-looking part is illustrated in Figure 1, which shows that after a period of very fast ‘hyperglobalisation’ between the mid-1980s and 2008, the share of world trade in world GDP has stayed roughly constant.

Figure 1 World trade relative to world GDP (1970-2018)

Note: Trade is defined as the sum of exports and imports of goods and services.

Source: Antras (2021), based on World Bank’s World Development Indicators (link).

Looking forward, Antras argues that two out of three main factors that explained ‘hyperglobalisation’ are unlikely to reverse. First, new technologies will continue to foster trade, because those substituting (foreign) labour (such as robotisation or 3D printing) still generate increased demand for traded goods (such as machines or IT parts). Second, the high sunk costs of establishing global supply chains make them resilient to temporary shocks and re-shoring only attractive for very persistent shocks. The only hyperglobalisation factor risking to reverse is multilateral trade liberalisation. To the extent that agents perceive the COVID-19 pandemic as temporary, it is unlikely to become a persistent de-globalisation force.

Susan Lund added that China rotating from exports to domestic consumption and building domestic supply chains can account for most of the global trade slowdown over the last decade (Lund 2021). As both reflect economic development, it may be regarded as a positive story, one other emerging economies may also go through in the future.

Climate change is likely to set in motion another set of major structural changes in the world economy. But Frederick van der Ploeg strongly warns of the great risk that policy responses will be too timid and too late, implying an unsmooth carbon transition with stranded assets and financial instability (van der Ploeg 2021). A sudden shift in climate policy or a technological breakthrough can lead to sudden changes in the market valuation of firms (so-called tipping events). Figure 2 (taken from van der Ploeg 2018) illustrates that the route of a cap to global warming taken by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (dotted line) would increase the carbon price (and therefore reduce carbon emissions and increase renewables) much faster than economists' preferred approach of pricing carbon at its estimated social costs (solid line). The reason is that economists' ‘Pigouvian’ approach does not take peak temperature constraints into account, and thus prices do not have to rise so fiercely under it....

more at Vox