|

|

Furthermore, the Task Force was mandated to review progress in relation to the policy proposals in the earlier report, as well as propose possible new policy actions aimed at mitigating potential systemic risks. As this column discusses, the new report finds that the low interest rate environment continues to pose risks for financial stability. For instance, since 2016, search-for-yield behaviour has intensified in the banking and investment fund sectors, and some business models are proving unsustainable. To address these sources of risk and vulnerabilities, the report puts forward a wide range of policy options.

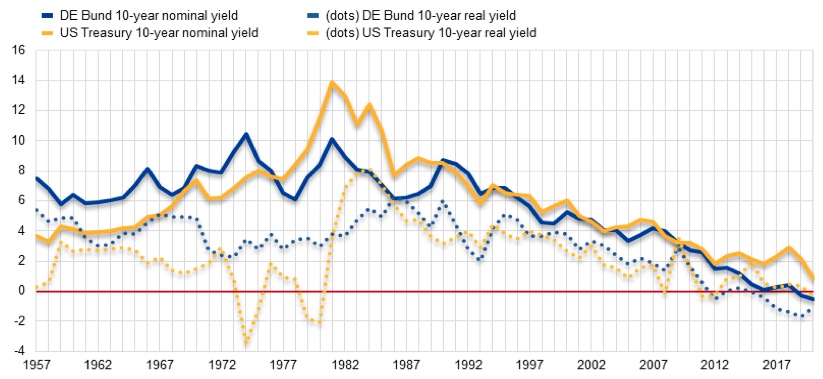

Nominal and real interest rates in the major advanced economies, short-term and long-term, have trended downwards since the early 1980s. We see this in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1 Short-term nominal and real interest rates in Germany and the US, 1965-2020 (%)

Source: OECD and ESRB calculations.

Note:

Short-term interest rates are based on three-month money market rates.

Real rates are calculated by subtracting the annual CPI inflation rate.

Figure 2 Nominal and real ten-year government bond yields in Germany and the US, 1957-2020 (%)

Source: OECD and ESRB calculations.

Note:

Yields are based on ten-year constant maturity government bond yields.

Real yields are calculated by subtracting the annual CPI inflation rate.

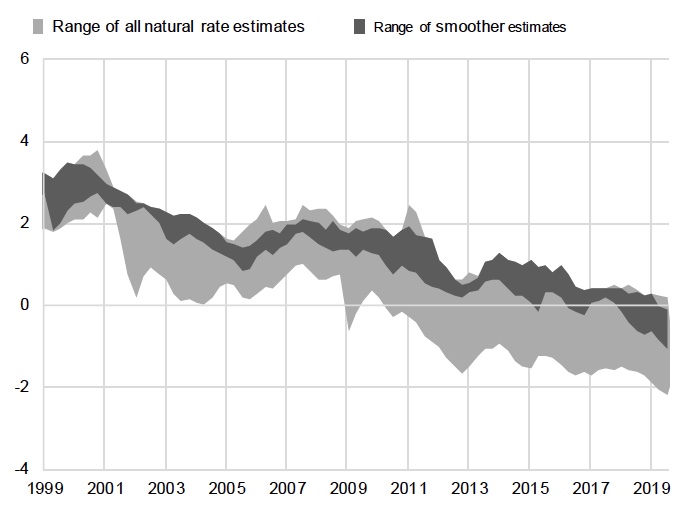

The ‘natural’ or ‘neutral’ equilibrium real interest rate R* that would support full employment at stable and low inflation is not directly observable. Many efforts to estimate it reach similar results, however, as shown for the euro area in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Estimates of euro area equilibrium real interest rate, Q1 1999 to Q4 2019 (%)

Source: Schnabel (2020).

Notes:

Ranges span point estimates across models to reflect model uncertainty

and no other source or R* uncertainty. The dark shaded area highlights

smoother R* estimates that are statistically less affected by cyclical

movements in the real rate of interest. Latest observation: Q4 2019.

With low and stable inflation, the decline in R* has forced policy rates down towards their effective lower bound. This now appears to be somewhat though not much below zero. Market rates too are very low. Whether policy rates or market rates, the low interest rate environment (LIRE) has implications for financial stability and therefore raises issues for macroprudential policy.

The European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB), which oversees macroprudential policy in the EU, has just published a second report discussing macroprudential policy issues arising from the LIRE in the EU financial system (ESRB 2021). This work began at the end of 2019 and builds on an earlier report, which the ESRB published in 2016.

The time horizon for our analysis is medium-term: five to ten years ahead. While the report acknowledges cross-country heterogeneity, its focus is mainly on the EU financial system as a whole and on interest rates in the EU.

The report begins with an analysis of how the LIRE has been driven mainly by structural factors, such as:

This literature is related to the ‘secular stagnation’ hypothesis revived by Summers in his speech at the IMF Research Conference in 2013. In addition, regulatory changes and the more risk-averse positioning adopted by financial institutions after the global financial crisis (GFC) have further boosted the demand for safe assets, putting more downward pressure on real interest rates and on risk premia. Many of these developments (and the trend decline in R*) hold not just for the euro area, but also for the US and Japan, and to some extent interest rates are transmitted globally (the ‘global financial cycle’; see Rey 2013).

Two recent analyses support ‘low for long’. Kiley (2020) reviews the literature and adds his own econometric study, concluding: “A range of approaches to estimating the equilibrium real interest rate confirm a pronounced downward trend among advanced economies in the level of real short-term interest rates likely to prevail over the longer term.” Gourinchas et al. (2020) agree: “Our estimates indicate that short-term real risk-free rates are expected to remain low or even negative for an extended period of time.”

But what about the COVID-19 shock? The report acknowledges that contractionary monetary policies (responding to a temporary rise in inflation) and increases in term premia (due to a temporary surge of uncertainty) could increase rates. If they were to occur, we would not expect such effects to be lasting. As long as the structural factors that have exerted downward pressure on the natural rate of interest persist, the LIRE will remain in place, at least in the medium term, according to the report. In fact, the report’s detailed overview of the effects of the COVID-19 shock concludes that it may have increased the probability and persistence of a ‘low-for-long’ scenario – so ‘even lower for even longer’.

The risk analysis of the report identifies four key areas of concern in the LIRE:

More at Vox