|

|

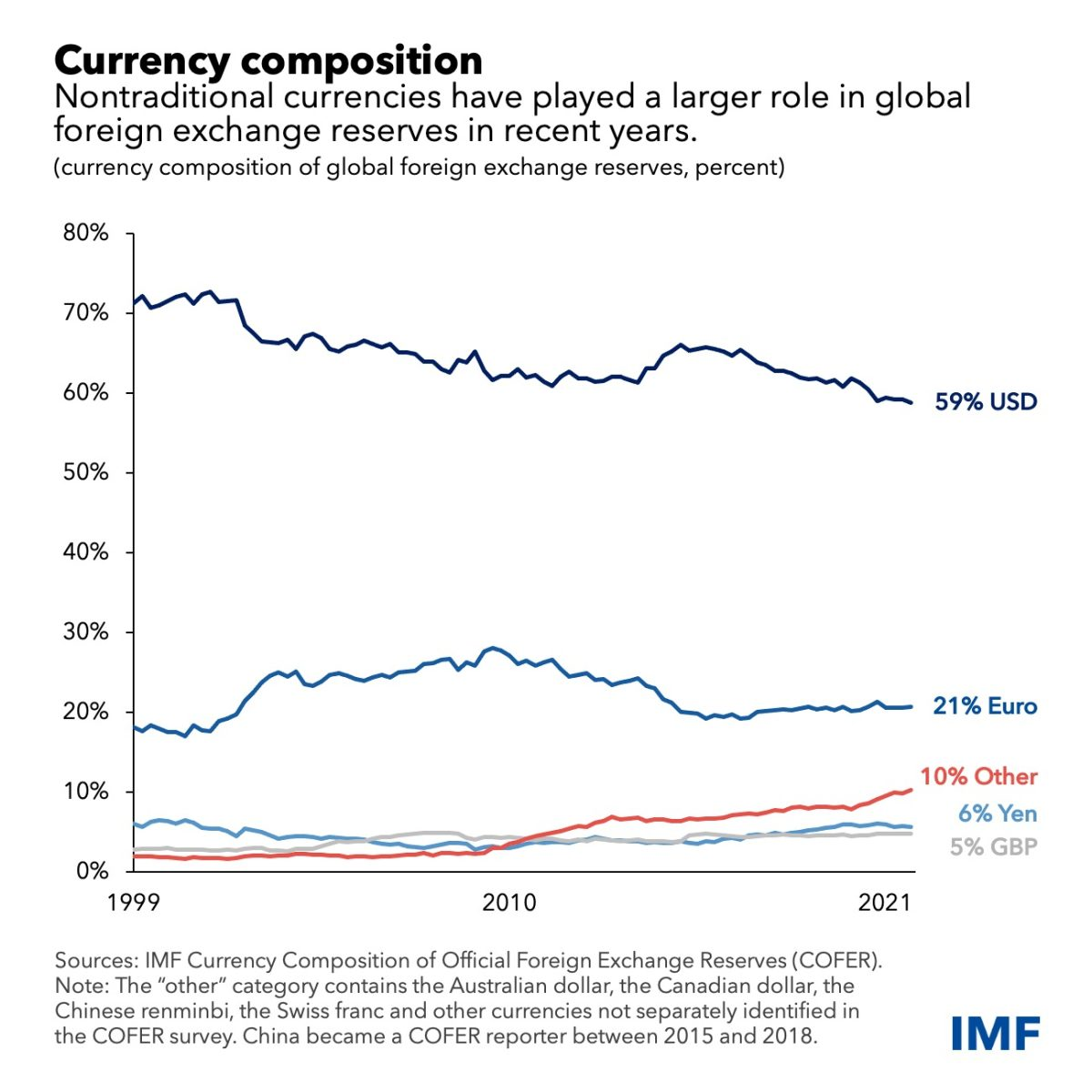

But although the currency’s presence in global trade, international debt, and non-bank borrowing still far outstrips the US share of trade, bond issuance, and international borrowing and lending, central banks aren’t holding the greenback in their reserves to the extent that they once did.

As the Chart of the Week shows, the dollar’s share of global foreign-exchange reserves fell below 59 percent in the final quarter of last year, extending a two-decade decline, according to the IMF’s Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves data.

In an example of the broader shift in the composition of foreign exchange reserves, the Bank of Israel recently unveiled a new strategy for its more than $200 billion of reserves. Beginning this year, it will reduce the share of US dollars and increase the portfolio’s allocations to the Australian dollar, Canadian dollar, Chinese renminbi and Japanese yen.

As we document in a recent IMF working paper,

the reduced role of the US dollar hasn’t been matched by increases in

the shares of the other traditional reserve currencies: the euro, yen,

and pound. Moreover, while there has been some increase in the share of

reserves held in renminbi, this accounts for just one quarter of the

shift away from dollars in recent years, partly due to China’s

relatively closed capital account. Moreover, an update of data

referenced in the working paper shows that, as of the end of last year, a

single country—Russia—held nearly a third of the world’s renminbi

reserves.