|

|

Mutual funds that allow investors to buy or sell their shares daily are an important component of the financial system, offering investment opportunities to investors and providing financing to companies and governments.

These funds may invest in relatively liquid assets such as stocks and government bonds, or in less-frequently-traded securities like corporate bonds. Those with less-liquid holdings, however, have a major potential vulnerability. Investors can sell shares daily at a price set at the end of each trading session, but it may take fund managers several days to sell assets to meet these redemptions, especially when financial markets are volatile.

Such liquidity mismatch can be a big problem for fund managers during periods of outflows because the price paid to investors may not fully reflect all trading costs associated with the assets they sold. Instead, the remaining investors bear those costs, creating an incentive for redeeming shares before others do, which may lead to outflow pressures if market sentiment dims.

Pressures from these investor runs could force funds to sell assets quickly, which would further depress valuations. That in turn would amplify the impact of the initial shock and potentially undermine the stability of the financial system.

Illiquidity and volatility

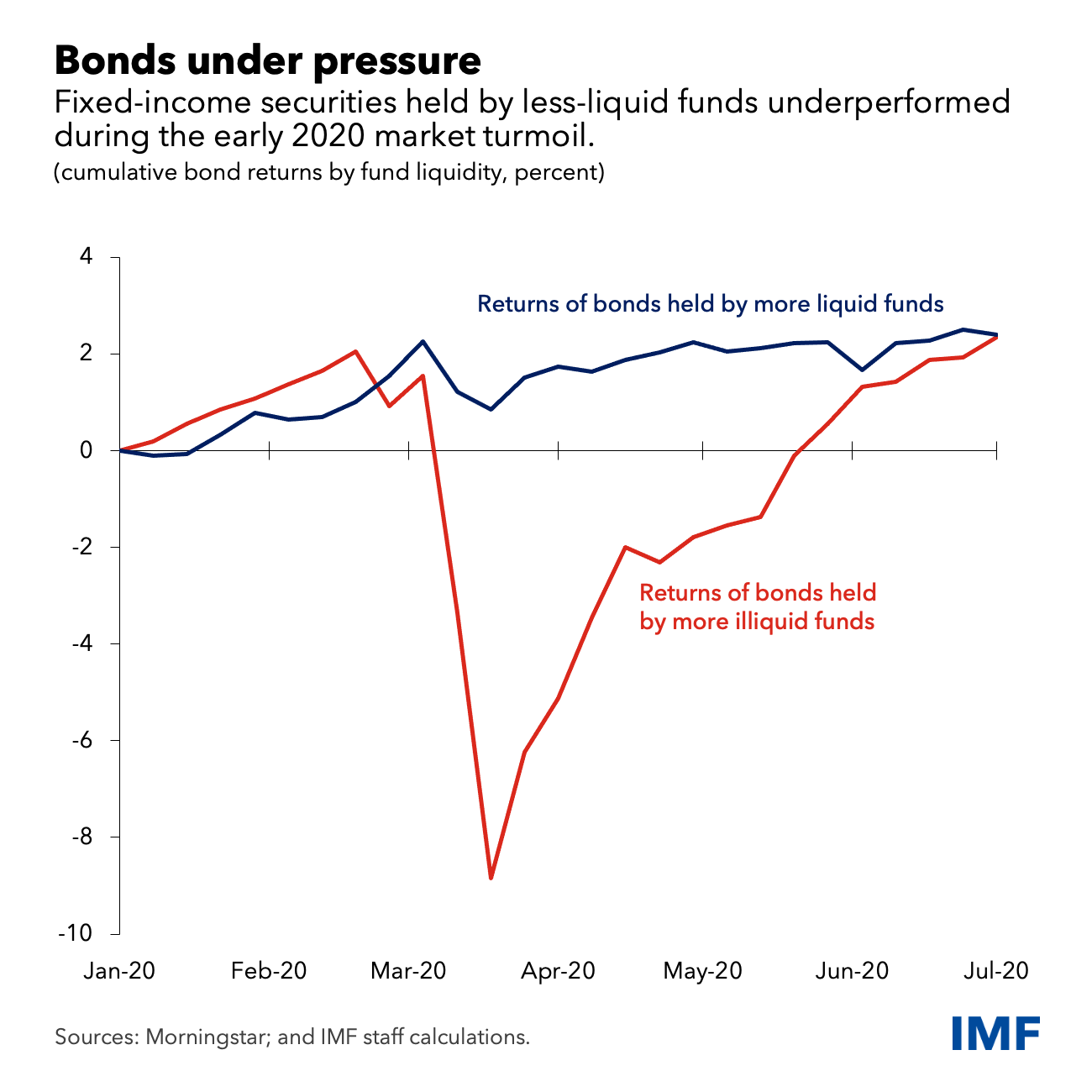

That’s likely the dynamic we saw at play during the market turmoil at the start of the pandemic, as we write in an analytical chapter of the Global Financial Stability Report. Open-end funds were forced to sell assets amid outflows of about 5 percent of their total net asset value, which topped global financial crisis redemptions a decade and a half earlier.

Consequently, assets such as corporate bonds that were held by open-end

funds with less-liquid assets in their portfolios fell more sharply in

value than those held by liquid funds. Such dislocations posed a serious

risk to financial stability, which were addressed only after central banks

intervened by purchasing corporate bonds and taking other actions.