|

|

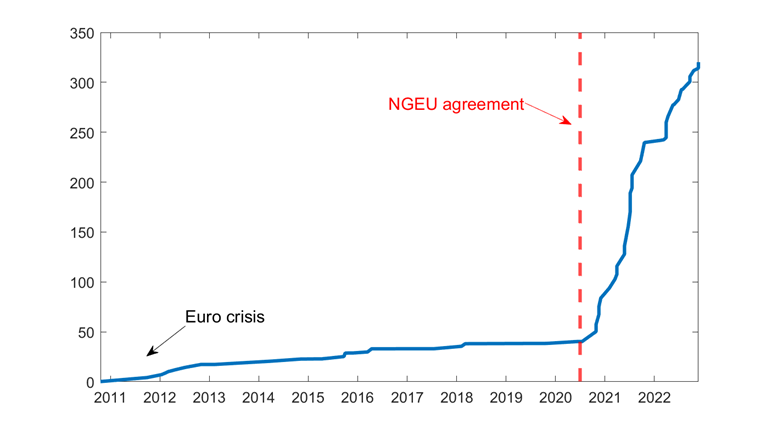

The COVID-19 pandemic led to a dramatic change in common borrowing by the European Union. With the introduction of SURE (Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency) and NGEU (NextGenerationEU) – programmes unprecedented in size and objectives – the EU shifted from being a small player in the sovereign market to a very significant one. EU debt (a slightly too broad concept, as discussed below) increased in two years from around €50 billion to over €300 billion (Figure 1). This has been widely considered a huge political success for the EU and a significant step forward in the integration process.

However, price data from the last few months showing rising interest rates on EU-issued debt has raised concerns about the ultimate success of the joint borrowing programmes. Five main observations can be made in relation to this.

First, EU borrowing comprises very different issuances with different guarantees. NGEU is by far the largest EU bond programme ever. Until the pandemic, the EU was thought to be legally barred from financing its expenditure through joint debt. What common debt existed involved either ‘back-to-back funding’ (transferring by the European Commission of borrowed amounts to EU countries on the same terms as received by the Commission), as opposed to borrowing for spending, or was issued outside the EU budget. The main issuers were the European Investment fund (EIB), the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) and the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF). The last two were created by international treaty to fund the bailouts of vulnerable countries during the euro crisis in 2010 (EFSF) and 2012 (ESM).

Figure 1: EU common outstanding debt, € billions

Source: Bloomberg. Note: excludes the European Stability Mechanism, European Financial Stability Facility and European Investment Bank.

Unlike these programmes, NGEU bonds, SURE bonds and Macro Financial Assistance (MFA) bonds are issued by the European Union and not member states, and thus we refer to them jointly as EU bonds. But they are by not identical. MFA debt is backed primarily by a Guarantee Fund for External Action, created by a contribution from the EU budget (MFA is an older and less significant programme that provides financial assistance to prospective EU members and neighbouring countries). SURE debt is guaranteed first by the margin that was available in the headroom (amounts authorised but not committed) in the EU budget, and the rest by an additional irrevocable and callable guarantees from member states. Both MFA and SURE are restricted to back-to-back lending.

The NGEU is novel in many ways. First, it is much larger. Second, the EU is borrowing in part (approximately half) to fund direct spending, rather than lending. Third, it does not involve a direct joint and several liability of EU countries, nor a specific guarantee. Instead the guarantee is the EU budget, through a temporary 0.6% increase in the headroom.

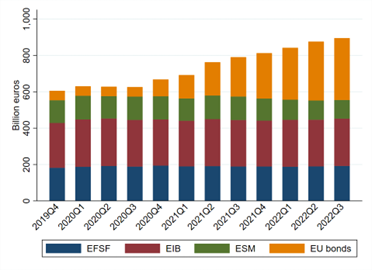

While the legal distinctions between issuing institutions are clear, the market treats all these debts as almost perfect substitutes for each other. Figure 2 shows the different EU issuance patterns. All the growth in outstanding issuance is due to the new programmes.

Figure 2: EU institutions, outstanding bonds denominated in euros

Source: Bloomberg.

Substantial amounts

Second, the size of the EU debt stock will be large: similar to the entirety of German federal debt. The EU has now issued substantial amounts of debt in a short period of time to fund a range of programmes, including €180 billion for NGEU and €92 billion for SURE. The issuance of these securities looked initially very promising, with the first issue in October 2020 registering the largest ever order book (€233 billion) for any single deal in the history of global bond markets. That was consistent with the expectation that by the end of the net issuance in 2026, the total size of this market will reasonably be above €1 trillion. This figure is obtained by summing the total amounts for the different programmes: €750 billion for NGEU, €100 billion for SURE, €50 billion outstanding from before and from new MFA arrangements, and adding inflation. The combined stock of debt obligations linked to the EU broadly considered, that is also including the EFSF, EIB and ESM, will thus reach a mass comparable to the current stock of German federal government debt (at €1.7 trillion)....

more at Bruegel