CEPR's Cechetti, Hilscher: Fiscal consequences of central bank losses

26 June 2024

This column develops a framework for understanding the medium- and long-run implications of the losses arising from these large-scale asset purchases, and argues that they are best viewed as a form of fiscal policy

“As the sole issuer of euro-denominated central bank money, the euro system will always be able to generate additional liquidity as needed. So, by definition, it will neither go bankrupt nor run out of money. And in addition to that, any financial losses, should they occur, will not impair our ability to seek and maintain price stability.”

ECB President Christine Lagarde, Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs Monetary Dialogue, 19 November 2020.

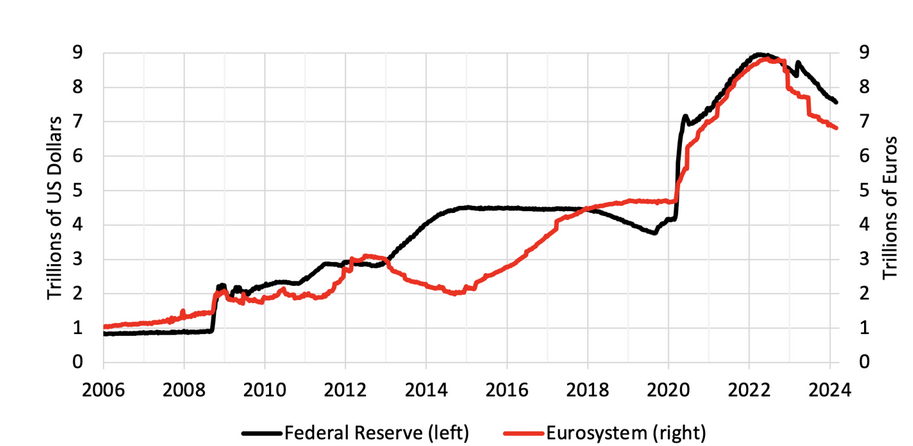

During and after the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-09, central banks engaged in large-scale asset purchase programmes, significantly increasing the size of their balance sheets. Purchases continued during the COVID-19 pandemic in the early 2020s. Figure 1 plots the consolidated assets of the Federal Reserve System and the Eurosystem. In both cases, total assets peaked at nearly ten times their level in 2008.

Importantly, central banks purchased bonds when long-term rates were low. So, when interest rates rose in 2022 and 2023, their holdings started to generate losses. This sparked a debate both over whether it was prudent to amass these portfolios and if the mounting losses would undermine the ability of central banks to meet their price stability objectives. Indeed, some observers argue that it is important to focus on both central bank capital and profitability, concepts that were previously of limited interest to researchers and policymakers. The idea seems to be that the valuation effects and implications for net interest margins – i.e. losses associated with large asset purchases – are of sufficient size to have welfare implications for society. In contrast, the above quote suggests that the central banks themselves are much less concerned.

In a recent paper (Cecchetti and Hilscher 2024), we develop a framework for understanding the medium- and long-run implications of the losses arising from central banks’ large-scale asset purchases. Specifically, we suggest that they are best viewed as a form of fiscal policy.

We arrive at this conclusion by consolidating the balance sheets of the central bank and the finance ministry. Consolidation clarifies that bond purchases change the maturity structure (and in some cases the gross quantity) of outstanding government debt. For example, large issuance of short-term reserves and concurrent purchases of long-term debt reduce the maturity structure of government liabilities, while leaving the overall quantity unchanged.

When monetary policymakers initially purchase bonds, their objective is to reduce longer-term interest rates, compressing some combination of sovereign term spreads and risk premia on private sector bonds. If successful, these policies stimulate aggregate demand, stabilising inflation, growth, and employment, and the financial system. Ideally, this reduces the length and severity of recessions, thereby increasing aggregate welfare. Policymakers generally do not focus on the potential for future profits or losses.

CEPR

© CEPR - Centre for Economic Policy Research