CER: The EU emissions trading system after the energy price spike

04 April 2022

The economic recovery from the pandemic has led to an energy crunch, and war in Ukraine has contributed to increasing energy prices and complicated the politics of carbon pricing. This policy brief discusses how to make a higher and more comprehensive EU carbon price both effective and politically feasible.

- Before Putin’s invasion of Ukraine,

the EU had planned to expand its emissions trading system (EU ETS) and

strengthen the carbon price it generates.

- The EU’s existing ETS establishes a carbon price for

heavy industry, electricity generation and intra-EU flights. However, to

maintain the competitiveness of European industry, many emissions

permits are handed out for free, which has so far dimmed the incentives

for industries to cut CO2. Carbon emissions from road

transport and building heating, so far excluded from the ETS, are priced

unevenly across the EU, with energy and carbon taxes varying across

countries.

- The EU’s Fit for 55 climate policy package aims to

change this, strengthening the role of carbon pricing in the transition

towards carbon neutrality by 2050.

- As part of this package, the

European Commission has proposed a lower cap on emissions, to bring the

ETS in line with tougher climate targets, and tighter conditions under

which industrial plants can claim free permits. Free permits will be

gradually phased out, while a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM)

will be introduced to level the playing field between the carbon price

faced by EU and foreign producers. The Commission has also proposed that

all ETS revenues that member-states receive should go towards climate

investment.

- These reforms go in the right direction, but should be stricter and implemented more rapidly:

- A

gradually increasing price floor, below which the price of emissions

permits cannot fall, would provide investors with certainty of the

direction of carbon prices.

- The current proposal envisions the

full phase-out of free allowances in 2036, ten years after the CBAM’s

full implementation. Scrapping free allowances for heavy industry by

2030 would force producers to innovate more quickly and would not make

European industry less competitive.

- Member-states should devote

ETS revenues to climate investment as planned – but more of that should

go towards low-carbon innovation.

- The European Commission

wants to introduce a new ETS (ETS2) covering emissions from road

transport and buildings, where decarbonisation is lagging. This would

impose a larger burden on poorer households and smaller businesses who

cannot easily afford to insulate their home or upgrade to more energy

efficient production processes. The EU wants to use part of the ETS2

revenues to help such vulnerable energy users and has proposed a Social

Climate Fund (SCF) to do so, but it could do more:

- All revenues from the ETS2 should be devoted to the SCF.

- The Fund should start as soon as possible: it would provide a good EU-wide response to recent energy price spikes.

- The

EU should clearly communicate that all revenues from ETS2 will be

devoted to supporting citizens and businesses in the green energy

transition. Without clarity on this link, popular support for carbon

pricing may falter.

- A ‘price corridor’ for ETS2 carbon prices

could help avoid excessive carbon price fluctuations. Households and

small businesses are not equipped to deal with large fluctuations in

their energy and fuel expenses.

- The EU should align all policies

concerning road transport and buildings with climate targets: reform of

the energy taxation directive is needed to remove energy subsidies

(such as those for aviation) and to ensure that high energy taxes do not

put electricity, which will become greener over time, at a cost

disadvantage relative to fossil fuels.

In the EU, not all CO2

emissions are considered equal: heavy industry and electricity

producers face an EU-wide carbon price under the EU Emissions Trading

System EU (ETS), but road transport and the heating of buildings do not.

All EU member-states tax fuel, but tax rates vary. And some

member-states have their own national carbon taxes in addition to the

ETS. This is about to change. In July 2021, the European Commission

presented the ‘Fit for 55’ climate and energy package, a set of policies

to cut carbon emissions by 55 per cent by 2030 relative to 1990 levels.

The package proposes reforms to tighten the EU ETS cap on emissions

from heavy industry and electricity generation, and to create a new

scheme to put a price on carbon emissions from road transport and

buildings.

Since 2005, the ETS has capped carbon emissions from

over 10,500 installations in the European power sector and in

energy-intensive industrial sectors such as oil refining, iron and

steel, and cement. The cap covers about 36 per cent of total European

emissions and is gradually tightened every year to reduce them.1

The cap is enforced via permits to emit, which are traded on carbon

markets, leading to a price for carbon emissions. The problem is that,

while the energy sector has cut its emissions by 15 per cent since 2005,

the carbon price from the ETS has, so far, not driven down carbon

emissions from heavy industry in a comparable way.

But prices on the European carbon market reached an all-time high of €100 per tonne of CO2

in early February 2022, as Europe’s climate targets – and its policies –

have become more ambitious. That is a welcome change from the first 15

years of the EU ETS, when heavy industry found that emitting carbon was

so cheap that reducing emissions was not worth the hassle. A carbon

price with bite is a necessary tool to reach the EU’s climate goals. But

a high price poses a challenge for Europe’s heavy industry, which

competes globally with producers who are not (yet) subject to comparable

carbon pricing.

The proposed ETS reform lowers the cap on

emissions to bring the ETS in line with tougher climate targets. It also

tightens the conditions under which industrial plants can claim free

permits, paving the way for their gradual phase-out. This will be paired

with the phase-in of a carbon border adjustment mechanism, which will

charge importers of some heavy industry outputs to the EU a fee based on

the EU carbon price, effectively levelling the playing field between

domestic and foreign producers.

The other main policy change

related to carbon pricing included in the Fit for 55 package is the

proposal to introduce a new system to cap and trade carbon emissions

from two major laggard sectors, road transport and buildings, which

account for about 25 per cent and 15 per cent of EU-wide greenhouse gas

emissions respectively.2

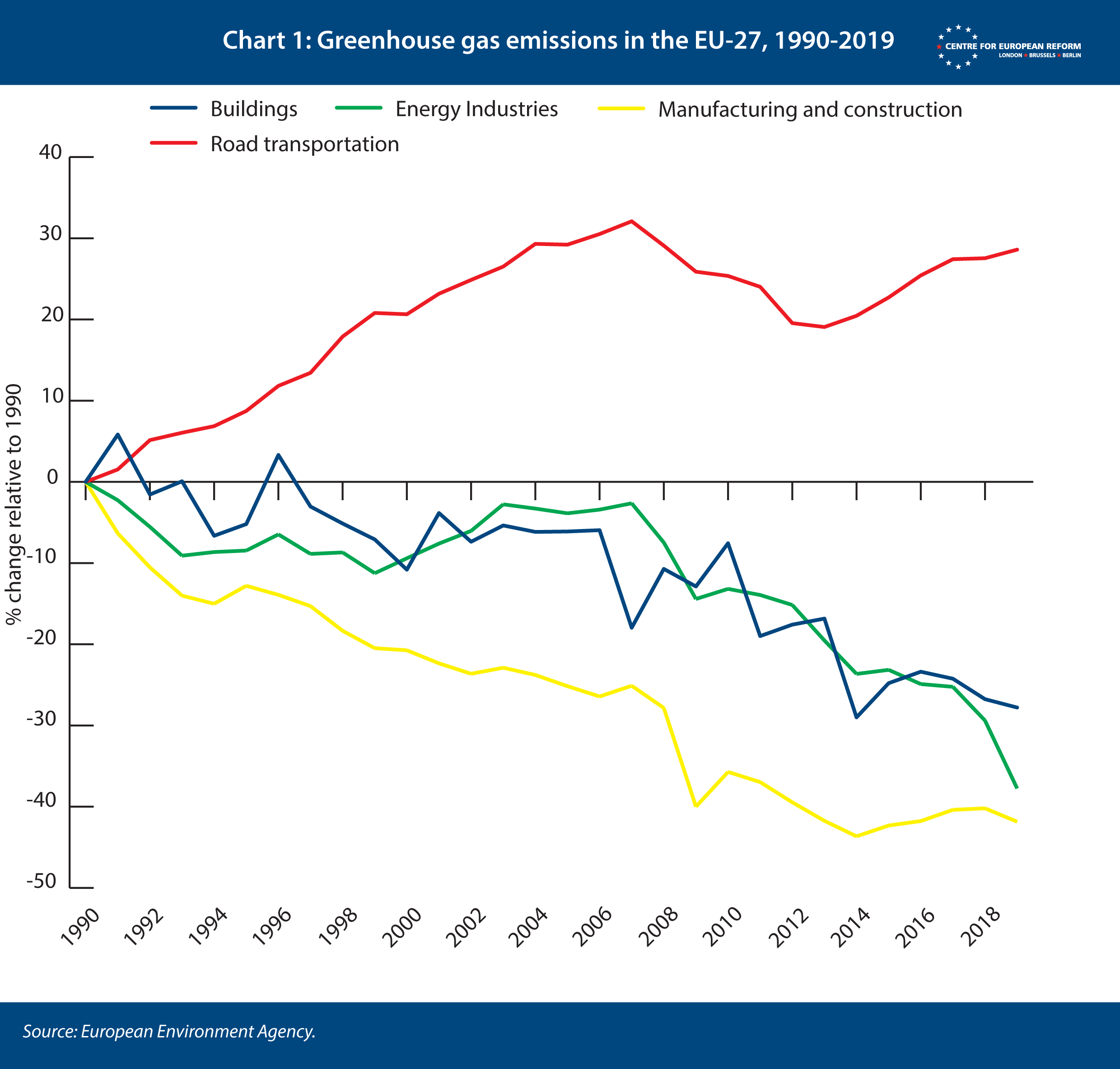

Manufacturing

and energy industries, currently covered by the EU ETS, have cut

greenhouse gas emissions since 1990 by about 40 per cent, while

decarbonisation in the commercial and residential building sector has

not been as fast, with emissions reductions below 30 per cent. However,

emissions from road transport have increased by almost 30 per cent (see

Chart 1). The new ETS aims to reverse this trend in transport emissions

and accelerate decarbonisation in buildings, cutting combined emissions

from these sectors by 45 per cent by 2030 relative to 2005 levels.

CER

© CER