It argues that the new system, while ending free movement with the EU and hence being far more restrictive for EU citizens moving to the UK for work, is considerably less restrictive.

Immigration

was central to the politics of Brexit (Hobolt 2016), but was peripheral

in the pre-referendum discussion of its economic consequences (Portes

2016). Indeed, both before and in the immediate aftermath of the

referendum, the UK’s choice was often framed as a tradeoff between the

economic costs of increasing trade frictions between the UK and EU on

the one hand, and the political benefits of ending free movement and

restoring ‘control’ over immigration on the other (e.g. Baldwin et al.

2016).

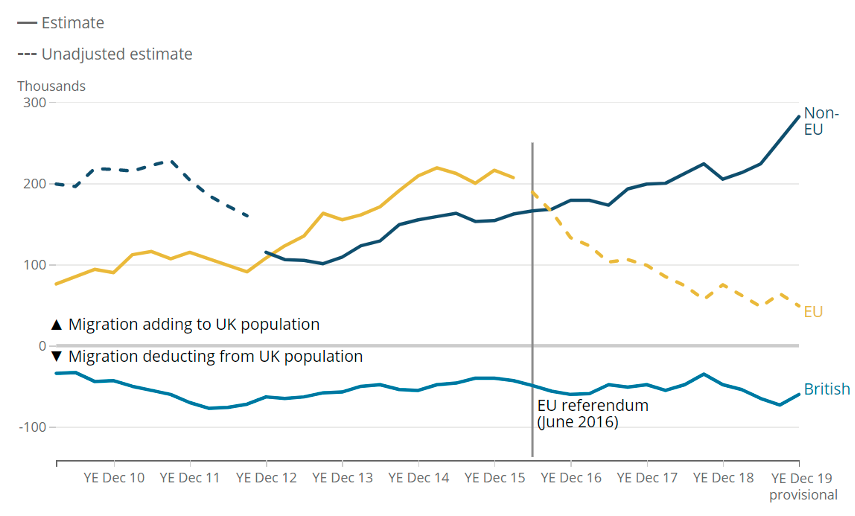

Since the referendum

this has reversed – immigration has become a much less salient

political issue, and public attitudes towards immigration have become

more positive (Runge 2019). However, its economic significance has

become more apparent, first as migration flows from the EU fell sharply

and then, in the past year, as the COVID-19 pandemic has led to very

large net outflows. Forte and Portes (2017) forecasted that net EU

migration could fall by up to 150,000 over the period between 2016 and

2020. These forecasts have proved broadly accurate. As Figure 1 below –

from the last set of published migration statistics, before the

pandemic made collecting them impossible – shows, net EU migration did

indeed fall by slightly more than 150,000 by the end of 2019.

Figure 1 Net migration by citizenship, UK, year ending March 2010 to year ending December 2019

Source: UK Office for National Statistics, 2020

At the same time,

there was also a significant rise in non-EU migration, facilitated by

government policy, with the cap on Tier 2 visas for non-EU migrants

(that is, relatively skilled or highly paid workers) being relaxed. This

marked the end of the Theresa May era in immigration policy, during

which the overriding objective of immigration policy had been to reduce

numbers. It is against this background that the UK is introducing the

new, post-Brexit immigration system. In a new paper (Portes 2021), I

discuss the new system, and outline some of the potential

implications.

As I set out in

Portes (2020), this system was shaped by two broad forces. First, the

government’s commitment to ending free movement and moving to an

‘Australian-style’ points system, which would treat EU and non-EU

migrants similarly. As a result, the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation

Agreement contains very limited provisions on labour mobility. But

second, significant shifts in both public opinion and government policy

towards immigration in general. Opinion polls suggest that voters have

simultaneously become both much less concerned about immigration and

much more positive about its impacts (Runge 2019). Moreover, the

replacement of Theresa May, who had been a notably restrictionist Home

Secretary, with Boris Johnson, who had adopted relatively liberal

positions on immigration during his tenure as Mayor of London, signalled

a change in the relative priorities within government attached to the

economic benefits of immigration compared to the political need to be

seen to be controlling it.

The policy intent of

the new system is therefore less about reducing migration, and more

about making it both more diverse (in a geographic sense) and more

selective (in relation to the skill level of workers). Free movement

ends and the new system will apply to all those moving to the UK to

work, apart from Irish citizens. EU (and EEA/Swiss) nationals already

resident in the UK are able to apply to remain indefinitely under the

“settled status” scheme, and most have already done so.

The key provisions of the new system are that:

new migrants

should be coming to work in a job paying more than £25,600 or the lower

quartile of the average salary, whichever is higher, and in an

occupation requiring skills equivalent to at least A-levels (“RQF3”);

there will be a

lower initial threshold for new entrants and for those in shortage

occupations, meaning that for some occupations the salary threshold may

be as low as about £20,000;

there will also be a lower threshold for those with PhDs, especially in STEM subjects;

for the National

Health Service and education sectors, there will in effect be no salary

threshold. If the job is at an appropriate skill, then paying the

appropriate salary according to existing national pay scales will be

sufficient;

there will be an

expanded Seasonal Agricultural Workers Scheme, but no other sectoral

schemes for workers who do not meet the skill threshold.

The new system

will represent a very significant tightening of controls on EU migration

compared to free movement. Migrants coming to work in lower-skilled and

paid occupations will in principle no longer be able to gain entry.

Even those who do qualify will need their prospective employers to apply

on their behalf, will have to pay significant fees, and will, as is the

case for non-EU migrants at present, have significantly fewer rights,

for example in respect of access to the benefit system.

However, compared to

the current system, the new proposals represent a considerable

liberalisation for non-EU migrants, with lower salary and skill

thresholds, and no overall cap on numbers. Approximately 68% of UK

employees work in occupations requiring RQF3 level skills or above.

Given the requirement for new migrants to be paid at or above the lower

quartile of earnings for that occupation, that implies about half of all

full-time jobs would be in principle qualify an applicant for a

visa. This represents a very substantial increase – perhaps a doubling

compared to the previous system for non-EU nationals, which was also for

most of the 2012-19 period subject to an overall quota and a resident

labour market test. It also makes the new system considerably more

liberal with respect to non-European migrants than that of most EU

member states, which typically apply much more restrictive (de facto

and/or de jure) skill or salary thresholds, and often enforce a resident

labour market test.

So, it is not the

case that the new system represents an unequivocal tightening of

immigration controls. Rather, it rebalances the system from one which

was essentially laissez-faire for Europeans, while quite restrictionist

for non-Europeans, to a uniform system that, on paper at least, has

relatively simple and transparent criteria, and covers up to half the UK

labour market.

In Portes (2021), I

discuss the potential economic impacts. The key point is that

economists’ views – including my own – on the potential impacts on the

UK economy of the end of free movement and the transition to the new

system may have been too pessimistic, based as they were on the

assumption the new system would be more restrictive. For example,

Forte and Portes (2019) estimated that the new system would result in a

reduction to UK GDP of up to 2% over 10 years. However, updating their

estimates to reflect the new system results in a much smaller fall in

GDP, and indeed a small rise in GDP per capita.

These estimates do

not take account of the broader impacts of migration, in particular on

productivity (Portes 2018, Goldin and Nabarro 2018), nor the interaction

of Brexit impacts with those of the pandemic and its aftermath. Some

sectors may be badly hit – for example, higher education

(Amuedo-Dorantes and Romiti 2021), and there are emerging signs of

labour and skills shortages in the hospitality sector, as many EU-origin

workers appear to have returned to their home countries during the

pandemic.

An additional

dimension of uncertainty results from the government’s decision to offer

entry visas to the almost three million British National Overseas

passport holders from Hong Kong, and their dependents. The Home

Office’s central forecast of the resulting migration flows (Home Office

2020) is about 300,000 over five years, but its low and high estimates

are 10,000 and 1,000,000 respectively. Actual flows will be driven by

developments in Hong Kong. If hundreds of thousands of Hong Kong

residents do come to the UK, the potential impacts could be

transformative.

So considerable

uncertainty remains. Nevertheless, while the overwhelming consensus

amongst economists that Brexit – and in particular the ‘hard’ Brexit

pursued by the UK government – will have significant negative impacts on

trade and investment, and hence on the broader UK economy, there is

much more cause for optimism about the impacts of the new post-Brexit UK

immigration system.

References

Amuedo-Dorantes, C, and A Romiti (2021), “Brexit deterred international students from applying to UK universities”, VoxEU.org, May 15.

Baldwin, R, et al. (2016), “Brexit Beckons: thinking ahead by leading economists”, VoxEU.org, 1 August.

Forte, G, and J Portes (2017), “The economic impact of Brexit-induced reductions in migration to the UK”, VoxEU.org, 5 January.

Forte, G, and J

Portes (2019), “Migration to Wales: the impact of post-Brexit policy

changes”, Welsh Centre for Public Policy, University of Cardiff,

February 2019.

Goldin, I, and B Nabarro (2018), “Losing it: the economics and politics of migration”, VoxEU.org, October 24.

Hobolt, S (2016), “The Brexit vote: a divided nation, a divided continent”, Journal of European Public Policy 23 (9) 1259-1277.

Home Office (2020), Impact Assessment: Hong Kong British National Overseas Visa, October.

Portes, J (2016), “Immigration after Brexit”, National Institute Economic Review, November, 238, R13-R21.

Portes, J (2020), “Between the Lines: Immigration to the UK between the Referendum and Brexit”, DCU Brexit Institute Working Paper 12-2020, Bridge Network, Dublin, December.

Portes, J (2021), “Immigration and the UK economy after Brexit”, IZA DP No. 14425.

Runge, J (2019), “Overview of UK attitudes towards immigration”, Briefing, National Institute of Economic and Social Research, August.