|

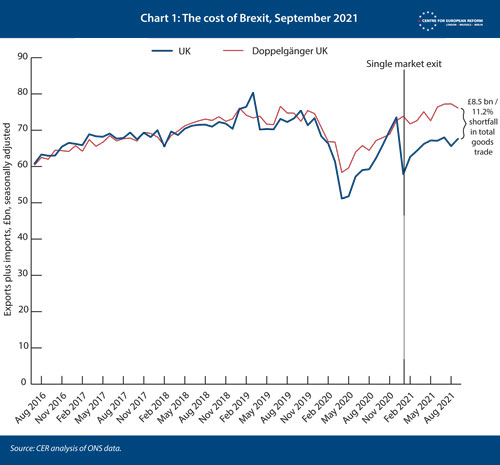

For many months the CER’s cost

of Brexit model model has found that UK goods trade is between 11

and 16 per cent lower as a result of leaving the single market and customs

union. Using the data for September 2021, the model puts the cost at 11.2 per

cent.

Last month, the UK’s fiscal watchdog, the Office of Budget

Responsibility (OBR), asked me to update my cost of Brexit model with the

August 2021 data for October’s ‘Economic

and Fiscal Outlook’. The reduction in the UK’s total goods trade –

imports plus exports with the EU and the rest of the world – was 15.8 per

cent, compared to a modelled ‘doppelgänger UK’ that did not leave the single

market and customs union in January.

In an update using the September data, the Brexit hit was a

little lower: Britain’s imports from outside the EU and exports to the EU

both ticked up, while total trade was down in the countries that make up the

doppelgänger – largely the US, Germany, Iceland and Greece (see Chart

1).

The doppelgänger is a subset of countries selected from a larger

group of 22 advanced economies by an algorithm. That algorithm finds the

countries that, when combined, create a doppelgänger UK that has the smallest

possible deviation from the real UK data until December 2019, before the

pandemic struck. (The data includes goods trade, GDP growth, population,

inflation, industrial production as a share of output, as well as some other

measures. More information on the model, including Stata code and input data,

is available here.)

The OBR noted that other estimates of the hit to goods trade were

around the same as those from my model. By the third quarter of 2021, the

global market share of British exports had fallen by around 15 percentage

points relative to the OBR’s March 2016 forecast. In other words, Britain’s

export share was always going to fall as China and other emerging economies

grew, but it has been falling faster than the OBR predicted before the 2016

referendum. And the degree to which UK domestic demand is satisfied by

imports has fallen by around 10 percentage points compared to the March 2016

forecast (which predicted a mild long-term rise).

So far, the hit to trade from leaving the single market and

customs union has been similar to pre-Brexit forecasts. The gravity

model we

constructed for our pre-referendum economic analysis of Brexit

predicted a 16 per cent drop. The OBR’s predicted 15 per cent, and the

British government’s long-term analysis predicted 10 per cent in 2018.

Gravity models are proven ways of measuring the effects of

tariffs, free trade agreements and the EU single market on trade. It is

harder to translate the hit to trade from Brexit into a precise estimate for

how much GDP will fall. Forecasts ranged from a 2 per cent to a 9 per cent

reduction in GDP compared to a UK that stayed in the EU. Before the pandemic

hit and the transition period ended, the

Bank of England, the

CER and Chris

Giles of the Financial

Times estimated that the economy was already between 1 and 3

per cent smaller, as a result of the depreciation of sterling, and foregone

consumption and investment. The effect of reduced trade after a single market

exit will come on top of that. So there is good reason to fear that the

OBR and the May

government’s estimates of a 4-5 per cent smaller economy by 2030

will be about right.

The economic consequences of Brexit have been largely met with a

shrug by the British political class so far, because it was a democratic decision

taken by a majority of the British public to leave the EU; Johnson won a

mandate for his form of Brexit, which included a high degree of autonomy and

relatively low economic integration with the EU; and Labour is only weakly

raising the issue, because they want to attract Leave voters. But a loss of

4-5 per cent of GDP is a big deal. According to an

analysis by Ian Mulheirn of the Tony Blair Institute, all of the tax

rises that the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rishi Sunak, announced in the

2021 Budget were down to Brexit reducing the size of the economy, and

therefore tax revenues. Poorer UK regions are

being hit harder by reduced trade with the EU, as we

predicted before the referendum. Thus, Brexit is making ‘levelling

up’ even harder. And in general, governments everywhere would leap on any

policy that would raise GDP by 5 per cent.

The mounting evidence of Brexit’s sizeable economic costs come

before the UK has implemented full border checks on imports from the EU.

Already, the evidence shows that the country can ill-afford a trade war over

the Northern Ireland protocol – which, thankfully, Boris Johnson and his

Brexit negotiator, David Frost, appear to be backing away from. But, unless a

new government is installed that is willing to renegotiate the UK-EU Trade

and Co-operation Agreement and opt for closer economic integration, the UK

will be a significantly more closed economy in the future, and a smaller one

at that.

John Springford is deputy director of the Centre

for European Reform.

|