..recent polling showing that a record number of people have changed their minds about Brexit, Paula Surridge and Alan Wager unpack shifting public attitudes, looking at age, education and changing geographic patterns, highlighting that Brexit may continue to shape our politics for some time yet.

In the past few weeks, the political conversation around Brexit had

shifted. This has partly been driven by change at the top of government,

and (intermittent) signals of a new approach. But it has largely been

driven by the polling evidence which has been moving for some time: YouGov’s

tracker found a record low number of people (32%) saying that, on

reflection, the decision to leave was the right one, versus 56% saying

Brexit was a bad idea in retrospect.

However, politically it matters not just how many people have changed

their mind. It also makes a difference who those people are, and where

they live. Furthermore, it is also important to understand not just what

people think about the past, but how this translates into attitudes

about the UK’s future outside the EU.

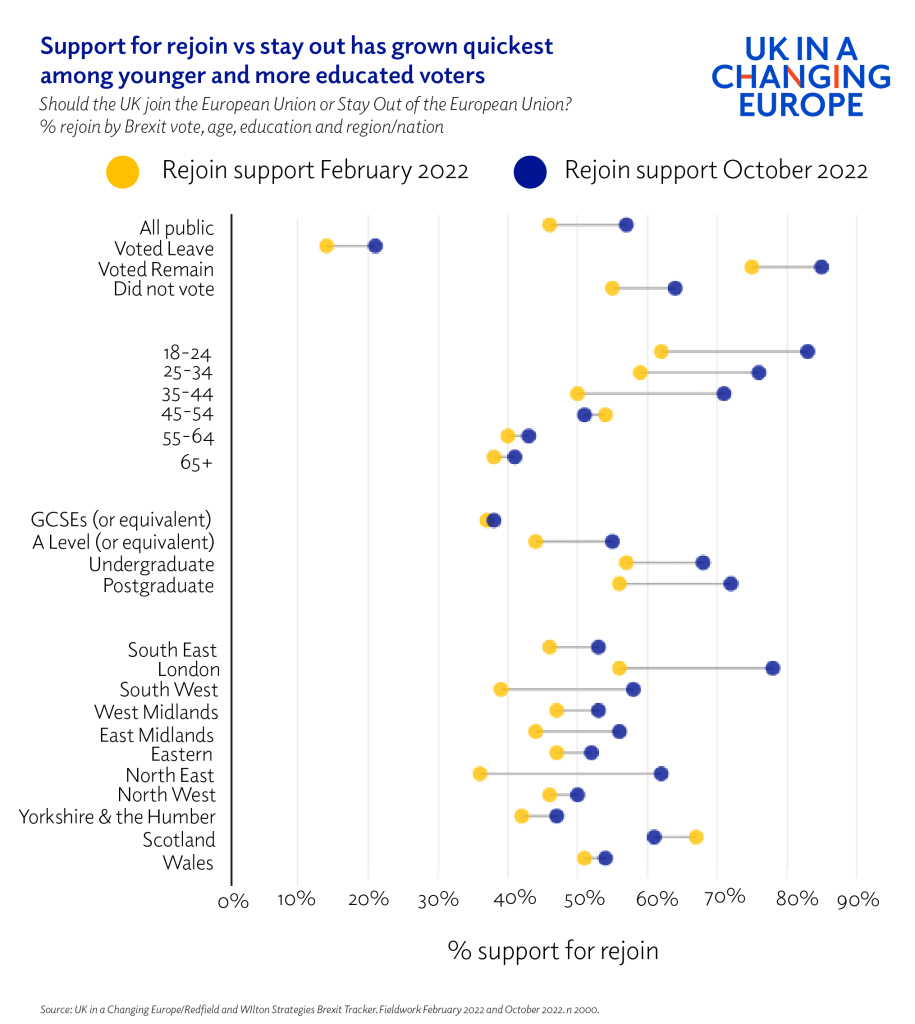

Our Brexit Tracker at UK in a Changing Europe,

in conjunction with Redfield and Wilton Strategies, has been running

now for almost a year and regularly asks the question of whether the

public thinks the UK should rejoin the EU or stay out. The graph below

shows how views have changed on that question throughout 2022.

Firstly, we can see a 12-point shift from the start of the year

towards the idea of rejoining the EU. Perhaps unsurprisingly (though not

inevitably, given remaining and rejoining are two different things) who

voted Remain or did not vote at all in 2016 are most likely to have

moved into the ‘rejoin’ column in the last 12 months. But, added to

this, there is a growing number of those who say they voted Leave in

2016 now say they would vote to rejoin the EU (from 14% of 2016 Leavers

to 21%). This roughly aligns with the one in five Leave voters who

YouGov found now think Brexit was a bad idea.

However, when we drill down into age, we can see a growing Brexit gap

between younger and older voters. In each age band under 45, support

for rejoin has risen by around 20 percentage points since the start of

the year. Meanwhile, there has been no statistically significant shift

at all among older voters, and those over 55 are still more likely to

state support for staying out over rejoining.

Professor Ben Ansell’s

analysis on his Substack of the Conservative Party’s ‘death spiral’

pointed towards a growing education chasm when it comes to vote

intention, with the Conservative Party now only leading among over 50s

who were educated to GCSE level. We see some very similar dynamics in

Brexit perceptions here: those educated to GCSE level retain their low

support for rejoin, barely rising from 37% to 38%. Meanwhile, support

for rejoin among those with an undergraduate degree has increased from

57% to 68% between February and October, and support for rejoin among

those with a postgraduate degree has grown from 56% to 72%.

This translates into some geographic patterns that confound conventional narratives. Just as the Tony Blair Institute

found last month, it is voters in the North East who appear to be among

those who have turned most negatively against Brexit: while these

regional cross-breaks should be treated with a degree of caution, our

tracker finds support for rejoin has risen from around 40% to around 60%

in the North East and the South West.

Our recent work on levelling up

found these areas that have moved towards rejoin were the parts of

England with the greatest scepticism about politics at Westminster. It

may be that scepticism about politics and euroscepticism are not quite as intertwined as they once were.

In one sense, these patterns around who has changed their mind are

largely academic. There is virtually no chance of a referendum on this

question, either in this parliament or the next. Yet the shifting

patterns of support can tell us how Brexit may continue to shape our

politics.

This data reinforces the view that the debate around the UK’s

relationship with the EU is far from settled. It is those sections of

the electorate who are either by nature (older voters) or education

policy (those without upper-secondary qualifications) growing

ever-smaller over time who are least likely to be increasingly persuaded

of the case for rejoin.

It is notable that these patterns partly mirror what we are seeing in

polling on vote intention. The educational cleavage we saw in 2016 and 2019,

with a growing gap between graduates and non-graduates, is not going

away and is, if anything, widening. This suggests that, despite its

lower salience, perceptions of Brexit continue to be related to

attitudes to party politics. What this data can’t tell us is whether the

reputation of Brexit is suffering due to the Conservatives’ broader

woes, or vice versa.

While some of the old patterns of age and education are familiar,

there is an emerging new geography of support for Brexit. What is clear

is that while Boris Johnson may have left office claiming that ‘Brexit

was done’, it seems that the public opinion is far from settled.

By Professor Paula Surridge, Deputy Director, and Dr Alan Wager, Research Associate, UK in a Changing Europe.

UK and EU

© UKandEU

Key

Hover over the blue highlighted

text to view the acronym meaning

Hover

over these icons for more information

Comments:

No Comments for this Article