Jonathan Portes assesses the extent to which predictions about trade and migration before the Brexit vote have materialised, highlighting that trade has been reduced by additional barriers but the extent to which liberalisation would increase migration flows in the short term was underestimated.

Pre-referendum predictions

Leaving the EU single market means increased barriers to trade in

goods and services between the UK and the EU (and the European Economic

Area), and the end of free movement of people in both directions. It also implies a reduction of such barriers between the UK and the rest of the world.

In other words, just as EU membership led both to trade creation, as

trade between the UK and other Member States increased, and trade

diversion, as UK trade with the rest of the world decreased, Brexit

should lead to the opposite: ‘trade destruction’ and ‘trade reversion’.

Similarly with migration: it follows that the overall impact on the

volume of UK trade and migration from Brexit is theoretically ambiguous.

However, economists were almost unanimous that it would in practice

be negative. The EU is by far the UK’s largest trading partner and the

EU Single Market is more than a free trade area; it is an area of deep

economic integration. Empirical estimates of the impact of Brexit on

trade therefore suggested that reduced trade barriers to the rest of the

world post-Brexit, while beneficial, would do little to outweigh the negative impacts of increased barriers with the EU.

Modelling

by the UK government estimated that, assuming an FTA with the EU that

provided for tariff and quota free trade with the EU, but little or no

regulatory convergence, meaning large increases in non-tariff barriers,

UK-EU trade volumes would fall by about 25 per cent. Meanwhile, even

under optimistic assumptions about possible FTAs with non-EU countries,

trade volumes with the rest of the world would only increase by about 5

percent, resulting in a net fall of about 10%. Consistent with this, the

UK Office of Budget Responsibility, forecast a fall in UK trade intensity of about 15%.

The consensus on immigration was similar; that Brexit would lead,

directly, through the end of free movement, to a sharp fall in

immigration from the EU, only partially offset by discretionary

liberalisation to the rest of the world. I initially estimated that EU

migration would fall by about 70%, while non-EU migration might increase

by about 10%. However, this predated the fall of Theresa May; the

Johnson administration switched tack. Revised estimates suggested

that while EU migration would still decrease very considerably, perhaps

by 60%, non-EU migration might increase by about 30%.

Trade impacts

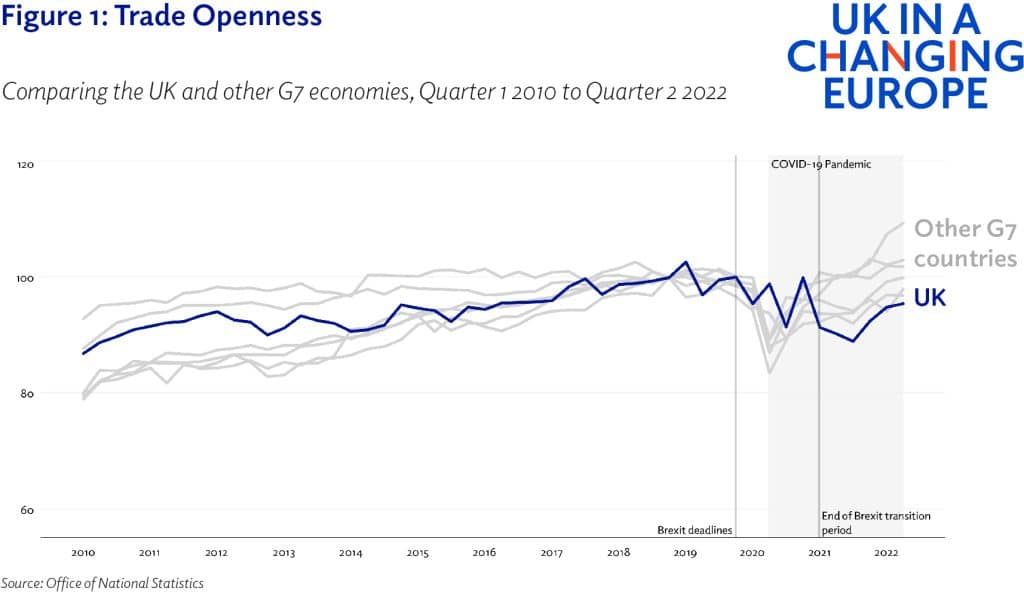

So how do these assessments compare with outcomes? On trade, at an

aggregate level, the impacts are consistent with the predictions

described above. UK trade performance since the implementation of the

TCA has been extremely weak, with the UK largely missing out on the

broad-based recovery in global trade volumes. UK trade openness (the sum

of imports and exports compared to GDP) has fallen significantly

relatively to other G7 countries. More detail on recent trends is shown

in our new trade tracker.

However, closer examination

reveals some puzzling aspects of the data. UK imports from the EU fell

considerably, although they have since recovered somewhat, despite the

fact that the UK did not impose the full range of regulatory checks

provided for under the TCA and WTO rules – while imports from the rest

of the world have risen, although the most recent data reflect large

rises in energy prices. Meanwhile, exports to the EU, while weak, have

moved broadly in line with those to the rest of the world; there is no

obvious differential effect, although some analyses do find significant impacts.

So while this outcome is hardly comforting for the fringe minority

of economists who argued that increases in trade with the rest of the

world would match or even outweigh losses from EU trade, it also poses

challenge to mainstream analyses. It may be that “deep” agreements like

the EU have much more complex impacts than simply removing trade barriers, relating to the globalisation of supply chains.

Migration impacts

Meanwhile, on immigration, the predicted decline in EU migration –

exacerbated by the pandemic and its aftereffects – has evolved much as

forecast. Before the pandemic, EU migration fell considerably, largely

offset by substantial increases in non-EU migration, although much of

this reflected an increase in the number of international students.

However, although there is huge uncertainty about the accuracy of the

data, the best estimates available suggest that these trends have

continued.

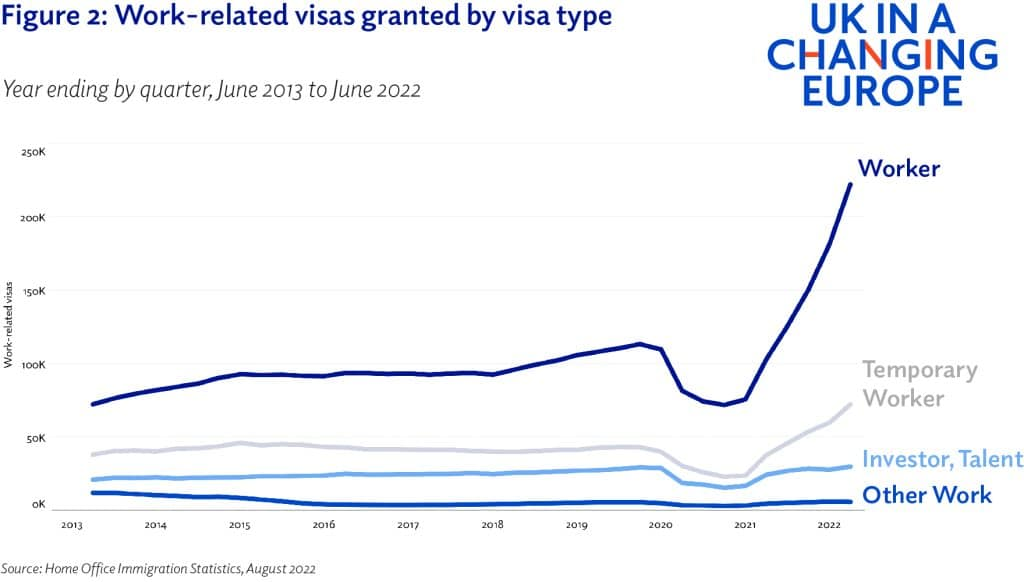

Indeed, subsequent to the introduction of the post-Brexit migration

system, increases in non-EU migration have significantly exceeded

expectations. The number of skilled worker visas has approximately

doubled compared to pre-pandemic levels; this is driven by an increase

in the number of visas granted to non-EU nationals, especially Indians,

Filipinos and Nigerians, rather than the post-Brexit requirement for EU

nationals to secure a visa (EU nationals only represent approximately

10% of work visas). Similarly, there have been very large falls in the

number of EU nationals coming to the UK to study, more than

counterbalanced by a sharp increase in non-EU nationals, with

particularly large increases in those coming from India, Pakistan, and

Nigeria.

Overall, while data is patchy, overall net migration to the UK for

work and study appears to be roughly similar to pre-pandemic levels, but

rising rapidly. So for immigration, contrary both to forecasts and to

trade patterns, ‘destruction’ of EU migration has indeed been at least

offset by ‘reversion’ of non-EU migration to countries that were large

sources of migration to the UK in the post-colonial, pre-EU era, as well

as in the early 2000s.

The new system in principle means that more than half of all jobs in

the UK labour market are open to anyone from anywhere in the world. And

post-pandemic labour shortages have meant that those employers who are

in a position to pay the substantial fees and navigate the required

bureaucratic processes have a strong incentive to do so. Meanwhile, the

introduction of a specific sub-category for workers in the health and

care sector, combined with very high levels of vacancies, has led to

large increases in international recruitment in this sector.

This is all visible in the sectoral profile of visas issued, with the

vast majority accounted for by the health sector and high-productivity,

high skill service sectors such as IT, finance, business and

professional services. Meanwhile, other sectors, more dependent on EU

workers in occupations that do not qualify for the new skilled work visa

– especially the hospitality sector – are seeing significant labour

shortages.

Conclusion

Overall, then, the picture is mixed. On trade, the basic intuition

that erecting new trade barriers with the UK’s largest trading partner

would reduce trade remains very much intact; but the causal mechanisms

look to be more complex than those in our standard models. On

immigration, while correctly identifying the likely impacts – a shift

from EU to non-EU, and from lower skilled to higher skilled migration –

we underestimated the extent to which liberalisation would increase

migration flows in the short term. And Brexit, while now ‘done’, remains

a moving target for economic analysis. Future political developments –

whether a trade war with the EU over the Northern Ireland Protocol, or a

political backlash against immigration – could require us to revisit

both our models and our assumptions.

By Jonathan Portes, Senior Fellow at UK in a Changing Europe.

This is an abridged version of evidence submitted to the

House of Lords European Affairs Committee inquiry. You can read the full

evidence submission here.

UK and EU

© UKandEU

Key

Hover over the blue highlighted

text to view the acronym meaning

Hover

over these icons for more information

Comments:

No Comments for this Article